The extraordinary Chalet Balthus

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Although only 20 minutes from jet-set Gstaad, Rossinière is a very different place. There’s no hint of a Louis Vuitton pop-up shop – in fact, not so much as a human being in sight on a wet Saturday afternoon. Mist hangs in the tops of the pine trees that clad the mountain sides, and the intricately carved and painted 270-year-old wooden façade of the Grand Chalet, the last home of the 20th-century painter Balthus, looms imposingly out of the fine desultory rain.

The largest inhabited wooden house in Switzerland – its 500sq m sprawling over five storeys illuminated by more than 100 windows – it is to Alpine architecture what the Great Pyramid of Giza is to pharaonic monuments. But although the detailed woodwork and traditional motifs are those of the world of Heidi, its ponderous grandeur sets it apart from the chocolate-box Switzerland of Johanna Spyri. Too grand for gemütlichkeit, it is perhaps best described as an example of Helvetian gothic.

Inside, lunch is served in a cosy dining room with walls and ceiling panelled with broad planks of the sort of blond wood you might find in a well-appointed sauna, with views out over the drizzle-dampened, chlorophyll-green meadows. At the head of the table sits the Countess Setsuko Klossowska de Rola, a petite porcelain-faced Japanese woman swathed in the meticulous folds of a traditional kimono. To her right is a languid well-dressed man with a shock of white hair and a beard carefully trimmed into the sort of point that suggests he has recently escaped from a Van Dyck portrait. To her left sits a willowy woman in a diaphanous floral frock whose unlined face belies the fact that in two years she will be 50.

They are, respectively, the painter’s widow, his son Thaddeus from an earlier marriage and Harumi Klossowska de Rola, his daughter with Setsuko. The last time I was here, Thaddeus, who was married to the late fashion muse and designer Loulou de la Falaise, had just published his diaries, which were enjoying a succès de scandale. I ask him what he has been doing since but before he can answer, there is an audible eruption beneath the table: part howl, part cough, part eructation. He casts his eye to the floor, flexes an elegant eyebrow and says to Harumi, “I think your wolf has just been sick.”

It takes more than a little lupine sputum to disrupt lunch at the Grand Chalet. Harumi wafts off and wafts back with a sponge and a towel, while Thaddeus explains that he is off to spend a couple of weeks in the medieval castle his father bought outside Rome, and Setsuko asks if I would like another helping of the delicious chanterelles risotto.

Vomit cleared, coffee served and hound dozing contentedly, Harumi explains the presence of a young wolf-dog, recently arrived from a breeder in Texas, in this sleepy Alpine village. “He is part wolf, part dog and gives me a better understanding of humans,” she says. “Wolves are very much like humans. They have a very strong pack mentality. The family unit is very important for them. The old ones are treated with a lot of care and respect by the younger ones. It’s interesting because I live here with my mother and half-brother. I also have Benoît [her partner, photographer Benoît Peverelli] and our two children. My assistant also lives here. Sometimes it’s complicated. I am in the middle, trying to arrange all kinds of energies.”

Among the complicated energies Harumi has to deal with are those of her late father, whose best-known work has become more controversial with time. Hers is not a reflexive defence of his legacy but a reflective acknowledge- ment of its complexity: “He not only painted pubescent girls but many still-lifes and landscapes; it’s a whole subject in itself that cannot be explained in a few words.”

Beyond the parallels she sees with her family dynamics, her work as a sculptor and jeweller is deeply rooted in an understanding of the natural world. “Not only are animals (and plants) inspiring my work, but I believe they are a link between us and nature. Through my work I am hoping to make us remember to respect them as animist civilisations did in the past,” she says. Such commissions can be big – including a 6m-high bronze tree inside which a spiral staircase will wrap itself on a client’s yacht – and small, such as her gem-set animalier jewellery, and the costume jewellery and objects she makes for the Parisian house of Goossens.

Happily, the Grand Chalet lives up to its name and is easily large enough to accommodate Harumi, her family, her animals, her work, her assistant and still have plenty of guestrooms when friends like Tilda Swinton, Wes Anderson (I bet he loves it here) or Wim Wenders decide to stop by. Since Balthus moved here in 1977, the Grand Chalet has welcomed musicians (think Bono and Bowie), artists (too many to mention), actors including Richard Gere and Tony Curtis and, of course, the Dalai Lama.

“I was four years old when we came from Villa Medici” – the palace where Harumi’s father directed the Académie de France à Rome. “My parents just came to have tea and then they discovered the house. My mother immediately fell in love with it because it reminded her of Japan. My father said he would love to have this house, so over a cup of tea it was done. His doctor had recommended a move to Switzerland because Italy was much too warm for him as he was suffering from malaria.”

For the 125 years prior to Balthus’s purchase, the Grand Chalet had been an hotel, of which traces remain – the bedrooms still have their room numbers painted on their lintels. “I vaguely remember that we inherited all the furniture from the hotel,” Harumi says of the surviving furniture, which runs the gamut from dining chairs to a vast armoire that, together with an ornately carved dresser, dominates the breakfast room. “It was less furnished when we arrived here. Some rooms were quite empty but, slowly, my mum put in closets and it became much more furnished.”

Typical of her mother’s additions is a large, well-lit, glass-fronted cabinet in which Japanese dolls are neatly marshalled alongside objects as diverse as the puppets she made to amuse Harumi when she was a child. “We have some Mayan things, some Chinese pieces and the cat collection of my father’s first wife,” she says, indicating a group of anthropomorphic feline figures.

The cabinet is a metaphor for the Grand Chalet in that it is stuffed with heterogeneous objects and curios, each with a meaning and a history. This is a house of character or rather characters, some living, some dead, whose tangled lives come together in a knot of Gordian complexity.

Harumi’s parents met in Japan, where Balthus had been sent by the French culture minister André Malraux to select works for an exhibition in France. “She was a young student and she was translating. My father fell immediately in love with her. He asked her to pose for him, and then she came to Villa Medici,” she says. “But my father was still married to Antoinette de Watteville, and he had his other girlfriend living there. It was a bit complicated for my mum, so she said she would leave him to sort things out while she went back to Japan. A year later he proposed to her, and they lived happily ever after. My father’s first wife was very close to my mum – to me she was like my grandmother, and I was partly raised by her. Every Christmas, the whole family would come here, her and her boyfriend, and my two brothers and their wives. So it was always a big, extended family.”

And it was to the Grand Chalet that she returned when she had a family of her own.

“I became very attached to this place – I love the mountains,” she says. “So even though I went to Paris, then lived in London and LA, I always had to come back here.” Harumi has led a cosmopolitan life: an education at Le Rosey, which she hated – “My father used to drive me in an old Peugeot and everyone else had Mercedes or Rolls-Royces” – and some more congenial years at Galliano then Valentino, where she has fond memories of working with Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli. That said, she refers to herself as “a country girl”.

The Grand Chalet is a palimpsest carrying the impressions made by previous generations of residents. The crooked 18th-century walls are hung, seemingly at random, with Balthus works – pencil studies, unfinished oils and smaller canvases – in between the souvenirs accumulated during a long life as one of the 20th-century’s most enigmatic and controversial painters. There is an Irving Penn portrait of saturnine Balthus in his prime; here and there are works from contemporaries he admired such as the Italian painter Morandi, one of whose bottle drawings hangs in the dining room.

Family-history-as-art crowds everywhere. A belle époque beauty painted in the manner of Lenbach is Harumi’s great-grandmother; while elsewhere a portrait of her mother by Martine Franck hangs near a drawing by her eight-year-old daughter. Even the cinema room on the first floor has an artistic accent – one of her father’s unused canvases is the screen onto which movies are projected. Then there is the studio where her mother works: an artist in her own right represented by Gagosian, she paints still-lifes, interiors and landscapes, as well as making ceramics – the white water jug with a cat scampering up the handle used at lunch is by Setsuko.

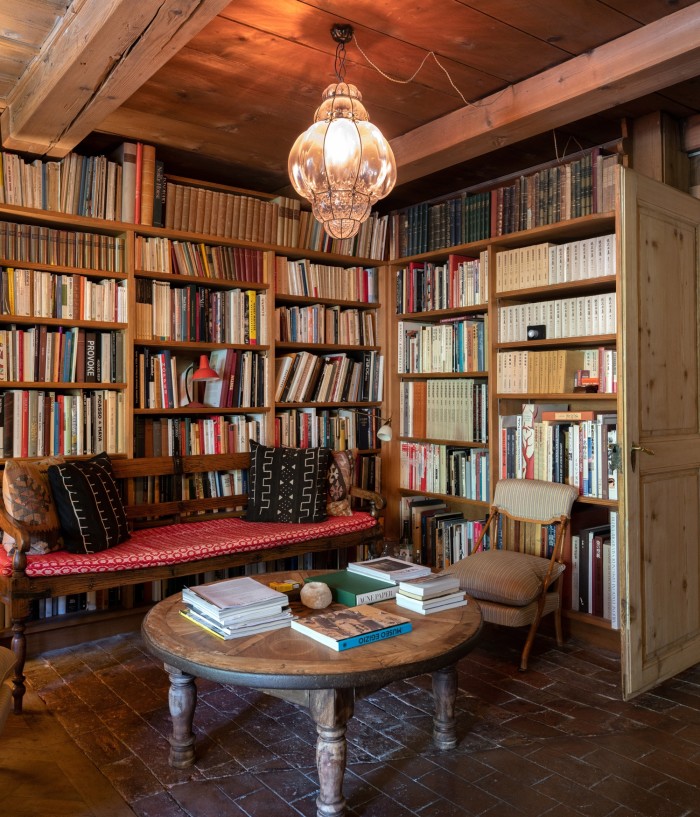

Harumi works in a number of spaces. At the front of the house is a library-like room with a giant open fireplace where she designs and displays her jewellery carved out of cow horn or fossilised wood, set with diamonds and embellished with gold. The Goossens jewellery using gilded brass and rock crystal depicts lions and dragonflies, and she is working on a new collection of decorative candlesticks and boxes. “I don’t produce a lot of things – I think it is better to keep it unique or in a small series,” she says. “I try to give a lot of importance to European craftsmanship, so I like how Goossens works in the old ways, by hand. Patrick Goossens still remembers my sister-in-law Loulou and his father working together – so our collaboration is a continuation and feels like family.”

The larger pieces are in the basement studio, formerly the hotel kitchen, where she sculpts objects in clay and creates screens of a Klimt-like richness using gold and platinum leaf. In recent years, she has turned her attention to furnishings. Typical are two monumental Lion benches that recall ancient Egypt and lend a strange formality to the cavernous basement, which used to be the hotel dining room.

Harumi has also used 4,000-year-old bog-oak trunks as the base for the creation of trompe l’oeil ponds in which bronze water lilies appear to float and tiny frogs can be found. The first was exhibited in the Valentino showroom in the Place Vendôme in 2018. “Pierpaolo showed some of his haute couture dresses along with some of my works that he thought would have a good ‘conversation’,” she says.

As her works become larger and more ambitious, Harumi has decided to move her studio into a separate building – a gaily painted shooting gallery that her mother brought from a fairground in Bern. It used to be a stable and is now being transformed. “There is more light and more space and I can be with my animals,” she adds. Among the first things to be finished is a new enclosure for her serval cat, a species more usually found in sub-Saharan Africa. The wolf-dog, meanwhile, is having a pergola-style enclosure constructed on the other side of the studio.

“It would all be very idyllic but for one thing: the wolf-dog and the cat do not get on right now – the serval cat hisses and growls when he is nearby. I hope they can get on with each other given time,” Harumi says. In this, the animals could learn a few useful lessons from the human inhabitants of the Grand Chalet.

Comments