Volatile markets increase appeal of ETFs with a buffer

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Latest news on ETFs

Visit our ETF Hub to find out more and to explore our in-depth data and comparison tools

Financial markets may have hit the buffers last year, but this did make one type of investment a lot more popular: buffered exchange traded funds.

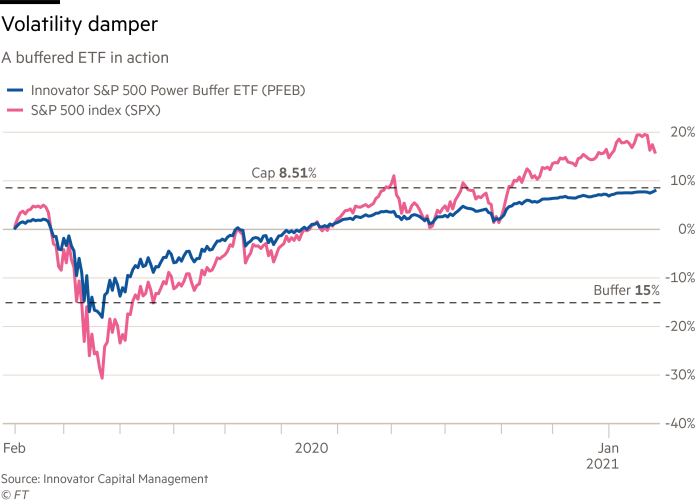

Also known as defined outcome funds, these ETFs use derivatives to give their investors a degree of downside protection, or buffer, if the market falls. In return, investors give up some of their potential gains, by having them capped — and the proceeds from doing this are used to buy the downside insurance.

In 2022, these funds raked in a net $10.9bn in North America, up from what had been a record $4.1bn the previous year, according to data from FactSet.

And further growth now appears likely, with BlackRock — the world’s largest asset manager — recently filing plans with the US Securities and Exchange Commission to launch its first two buffer funds.

However, two big questions loom over this fast-growing market: are buffered funds largely a bear market phenomenon that will be forgotten whenever the next bull market comes around; and are investors’ paying a fair price for the protection they get?

Graham Day, chief investment officer of Innovator Capital Management — which launched the first buffered product in 2016 and is market leader with $11.7bn of the $23.1bn held in North American funds, according to FactSet — is unsurprisingly optimistic that the concept is here to stay.

“We kind of cheer a little bit of volatility in the market,” says Day. “The market has been so complacent for the best part of 10-12 years, but volatility in the market is a normal thing and we have largely forgotten. I think a lot of people were anticipating a V-shaped recovery . . . People are now waking up the realisation that volatility is going to be normal going forward.”

Innovator’s best-selling range of funds are its 15 per cent “Power Buffer” ETFs. These protect against the first 15 per cent of any market loss over the course of a year.

The maximum return possible before hitting the “cap” on gains depends on market conditions when each product is reset once a year, but the April 2023 power buffer had a starting cap of 14.94 per cent.

Other products, both from Innovator and its rivals, can be structured so that investors incur some initial part of any loss, but gain protection after that.

BlackRock’s two proposed products, for example, are a “Moderate” buffer fund that would protect against the first 5 per cent of losses over each quarter, and a “Deep” buffer fund protecting against losses of between 5 per cent and 20 per cent.

Innovator’s Power Buffer ETFs have largely shielded investors from losses so far. Since inception, there have been only three 12-month periods in which the S&P 500 has fallen more than the 15 per cent buffer — impacting the ETFs Innovator issued in September, October and December 2021. In these three cases, underlying loses of between 15.9 and 19.5 per cent were transformed into smaller losses of 1.7 to 5.2 per cent, net of fees, by the buffer, according to Innovator’s data.

But Elisabeth Kashner, director of global fund analytics at FactSet, says investors are paying too much for this protection, given that annual fees are typically in the range of 75-85 basis points and investors also lose out on dividend income.

As a result, Innovator’s buffer ETF range that protects against the first 9 per cent of losses generated only annualised net returns of 8.4 per cent a year between April 2020 and the end of March, compared with the S&P 500 index’s 13.1 per cent, according to FactSet data.

Unsurprisingly, returns have been lower still for more conservative products, with the Power Buffer range returning an annualised 6.5 per cent over the same period, and the “Ultra Buffer”, which protects against losses of between 5 per cent and 35 per cent, returning 3 per cent.

Totting up the current yield on the S&P 500 and the fees, Kashner reckons investors were typically paying around 2.8 per cent a year for downside protection that might be as slim as 9 per cent.

“Not a single one of the clients who are in these funds would pay these rates for any other type of insurance, certainly not term [life] insurance,” she points out. “I would posit the argument that, of all the risks a household faces, their portfolio being down 10 per cent in a year or the breadwinner dropping down dead . . . the latter would be far worse financially.”

Kashner thinks more awareness is needed. “People are overpaying dramatically for insurance and there is no conversation around that,” she says. “If investors and advisers understood how expensive they are, they might be a little less enthusiastic about these products for long-term use.”

Nevertheless, Day maintains that Innovator is “adding a tremendous amount of value”.

“Where else can you find these products?” he asks. Compared to more traditional defined outcome offerings from banks and insurers, he suggests “our products are incredibly inexpensive [without] layered fees, commissions and surrender charges. Advisers like the ETF wrapper better. It limits credit risk and is available on the exchange.”

Todd Rosenbluth, head of research at data provider VettaFi, says the alternative for retail investors is “doing it yourself”, but “managing the downside and capping the upside using options directly is just too complicated and burdensome for most investors to want to handle”.

He believes that fees for buffered ETFs will fall as more competitors enter the market.

But whether they do so may depend on demand for the funds — which could fall if market volatility eases and fears about making losses diminish.

Day remains confident about their popularity, though, particularly as higher volatility increases the upside cap that buffered funds can offer — potentially making the products more attractive.

More broadly, even in a roaring bull market, “there is always going to be a segment of advisers and investors that want to invest more conservatively,” he argues. “Maybe [those] approaching retirement, wanting to protect the money that they have made. These products are still relatively new in the market and we still have a tremendous number of advisers who are just learning about them.”

Rosenbluth agrees. “I think they are here to stay,” he says. “We are seeing advisers build their products around using these ETFs.”

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

Comments