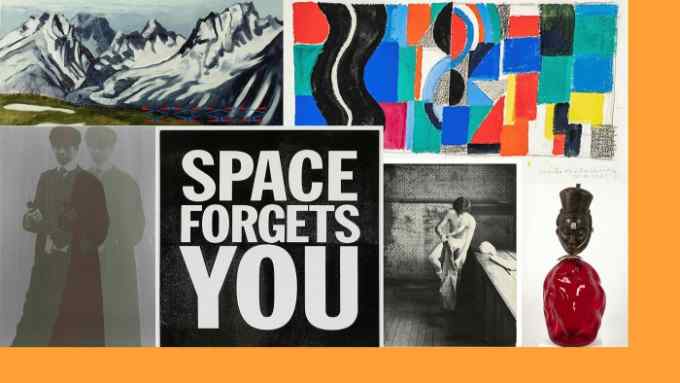

Female art dealers who made waves in the 20th century

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It is only in the past few years that women artists have started to take their rightful place alongside men — even if the price gap remains large. But the story of the women art dealers who supported them is just as compelling. Braving a still male-dominated world in the early 20th century, they promoted then unknown or even derided movements such as abstraction, kinetic art or Surrealism, along with female and black artists. There were many such dealers, some well-known names, others far less so. Here are just six of them.

Marguerite “Peggy” Guggenheim (1898-1979) needs little introduction: she was one of the outstanding art figures of the 20th century, and her legacy lives on in her Venice foundation. What is less well known is that she created a commercial gallery, Guggenheim Jeune, in a former pawnbroker’s shop at 30 Cork Street, London, between 1938 and 1939.

The name was an amalgam of the mega-wealthy Guggenheim family and the leading Parisian gallery, Bernheim-Jeune. When planning the project, she consulted Marcel Duchamp and travelled to Hans Arp’s foundry near Paris, seeing one of his sculptures cast in bronze. “The instant I felt it I wanted to own it,” she said. It was the start of an art addiction that would last for the rest of her life.

Guggenheim Jeune launched in January 1938 with 30 drawings by Jean Cocteau, including two linen sheets showing blood-splattered figures with their genitals and pubic hair on display — a gesture of support for the Republican cause in Spain. The works had been briefly detained on their way into the UK and the British censors demanded they be hung out of public view in a back office.

After this audacious opening, Guggenheim went on to give Wassily Kandinsky his first solo London show and promoted modern sculpture with works by Henry Moore, Arp, Constantin Brancusi, Antoine Pevsner and Alexander Calder. After she met the Surrealist painter Yves Tanguy, one of her many, many lovers, she held his first solo show in London, reaping critical success and sales. Afterwards, hoping to boost Tanguy’s reputation still further, Guggenheim offered the four most important remaining works to Tate — only to have them turned down.

Guggenheim would go on to create the Art of This Century gallery in New York in 1942, and in the following two years once again defied convention, holding exhibitions of female artists, among them Louise Bourgeois, Lee Krasner, Leonora Carrington, Louise Nevelson, Meret Oppenheim, Kay Sage, Dorothea Tanning, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Guggenheim’s own daughter, Pegeen. Curiously, Georgia O’Keeffe declined to be included, not wanting to be classed as a “woman artist”.

Meanwhile and also in New York, another pioneering art dealer was focusing on American modern art and folk art. Edith Halpert (1900-1970) was born in Odessa and arrived as a child in New York. She took classes at the progressive Art Students League — but got thrown out of her family home when they saw her drawings of a near-naked young man.

A formidable businesswoman, Halpert initially worked to support her artist husband Samuel and then used her bonuses to open the Downtown Gallery in the mid-1920s. The inspiration to open a commercial gallery had come from a trip to France, when Halpert contrasted the lively, successful Parisian spaces with the sluggish New York ones, still focused on European art.

The opportunity she spotted was for American art by living artists, and her gallery was the only one in New York at the time dedicated to their work. Over the years Halpert introduced Stuart Davis, Charles Sheeler, Marsden Hartley, Yasuo Kuniyoshi and many others to the American public.

As groundbreaking was her espousal of art by black Americans. In 1941, despite considerable financial challenges, she unveiled Negro Art in America, with 75 works by 41 African American artists — the first show of its kind in a commercial gallery. She also exhibited Jacob Lawrence’s heroic 60-panel “Migration Series”, documenting the 1910s exodus of African Americans from the rural south to the urban north. “Migration Series” finally sold, after much harrying on her part, jointly to the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where the series can be seen today.

While Halpert specialised in modern American art, Ileana Sonnabend (1914-2007) — born in Romania, former wife of the famed gallerist Leo Castelli — focused on American Pop art when she opened her eponymous gallery in Paris in 1962. “Everyone in Europe was looking forward to something new, to recover from the general feeling of boredom with the last waves of the Ecole de Paris,” she told the author Alan Jones in a 1984 interview.

When she arrived in France, she was no neophyte in the art world. She had arrived with Castelli in the US on the eve of the second world war, and they had immediately integrated into New York’s artistic circles. They met Marcel Duchamp and Jackson Pollock, and in 1950 had shown American and European painters such as Jean Dubuffet and Mark Rothko. They opened their first art space in 1957, exhibiting Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. But the long marriage ended and Sonnabend returned to Paris, where she first showed Johns’ flag paintings, followed by Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. The work was not always well received: seeing a group of Warhol’s “Marilyn” paintings, her landlady exploded, “I forbid you to show those things on my premises. This is not art, it’s necrophilia!”

Five years later, Sonnabend reversed the flow, opening in New York with European art of the 1970s. There she unveiled a Gilbert & George’s singing sculpture, followed by the likes of Mario Merz and Jannis Kounellis, later also promoting Jeff Koons, Vito Acconci and Ashley Bickerton.

Helen Serger (1901-1989) was born in present-day Poland, but she and her husband fled Europe in 1940. She founded the Manhattan gallery La Boetie in 1964 — named after the Parisian street. Her exhibition Pioneering Women Artists in 1980 featured Sonia Delaunay, Hannah Hoch, Alexandra Exter and Kay Sage, among others, while the 1988 Women Artists of the Avant-Garde, 1900-1940 included showcases for Anni Albers and Eileen Gray. All of this was to a backdrop of misogyny from some critics: the German early expressionist painter Paula Modersohn-Becker, shown a number of times at La Boetie, was castigated by one writer in 1984 as a “Madame Blavatsky on the Nile” [the founder of Theosophy] and “an Edwardian coquette.”

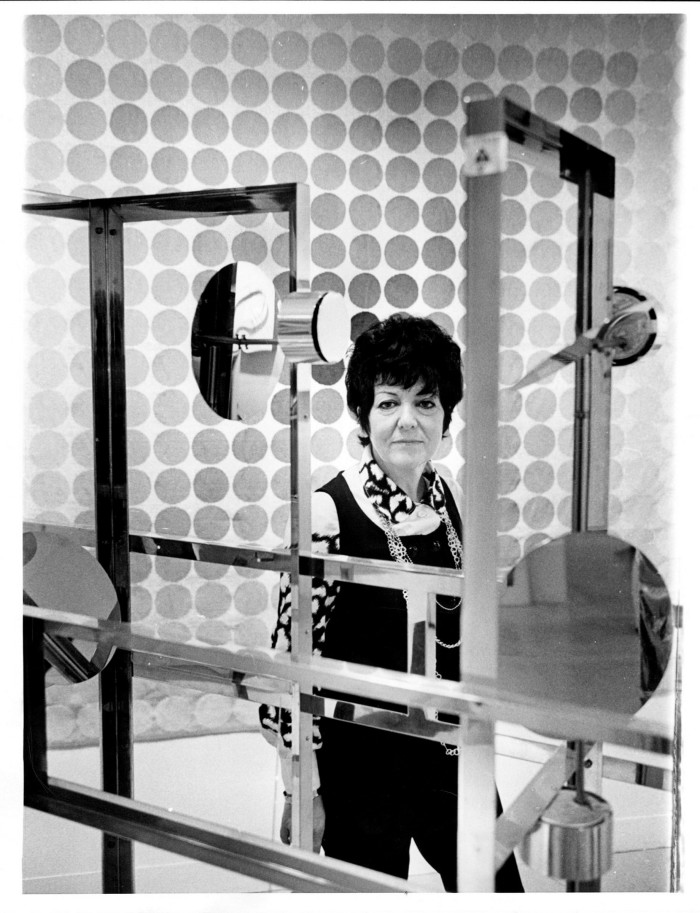

Meanwhile in Europe, the French gallerist Denise René (1913-2012) was one of the foremost promoters of abstract art, Op-art and kinetic art. She launched her eponymous Parisian space in 1945, initially showcasing artists such as Max Ernst (who was married at one point to Peggy Guggenheim), Francis Picabia, Jean-Michel Atlan and Charles Lapicque. But soon she was also showing Arp, Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, as well as the 1970s Op-art darling Victor Vasarely and Latin-Americans such as Jesús Rafael Soto. But René had her idiosyncrasies: she refused to exhibit Yves Klein, because his body paintings were “too figurative” for her, and Lucio Fontana, who she found “too negative” in the way he slashed canvas.

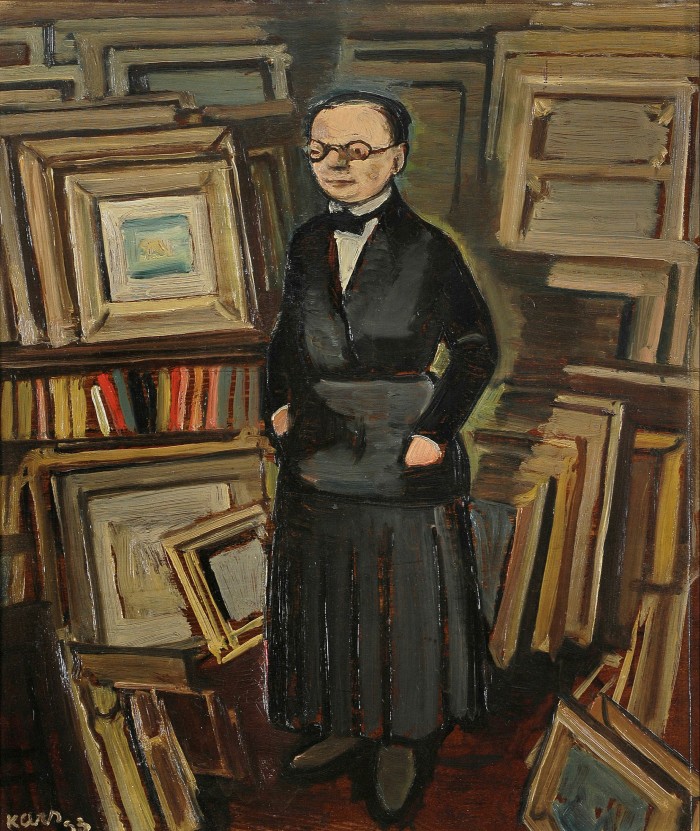

Almost forgotten today is Berthe Weill (1865-1951), and yet the tiny spinster “with spectacles thick as goldfish bowls”, according to Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, championed a host of significant artists. She opened her gallery in 1901 and gave the then-unknown Pablo Picasso his first show, before he even moved to France. She made the first sale for Henri Matisse. The list of artists she exhibited over 40 years is extraordinary, and includes Georges Braque, André Derain, Henri Manguin and Albert Marquet, as well as many unknown today. “We took the risk of going modern,” Weill explained in her memoir. And she was bold: she held Amedeo Modigliani’s only solo show in 1917, which was immediately closed down by the police on the grounds of nudity (it didn’t help that the gallery was right opposite the police station.) In 1941 she closed the gallery due to rising anti-Semitism . . . and died in poverty in 1951.

Comments