It’s stupid, it’s chaos – it’s love: Damien Hirst on his Cherry Blossoms

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

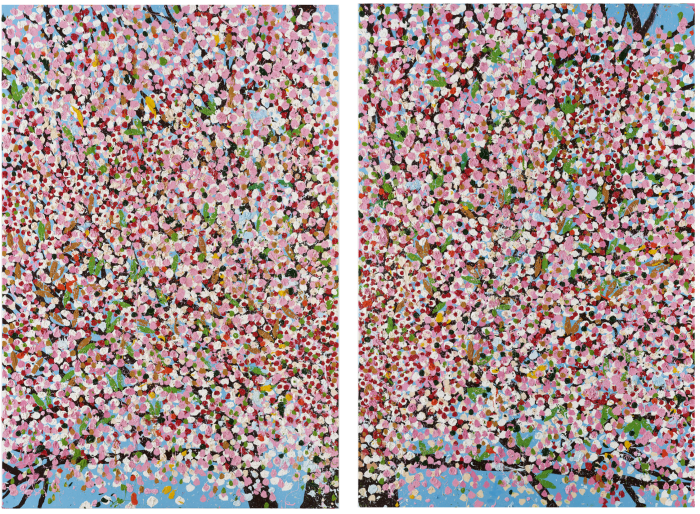

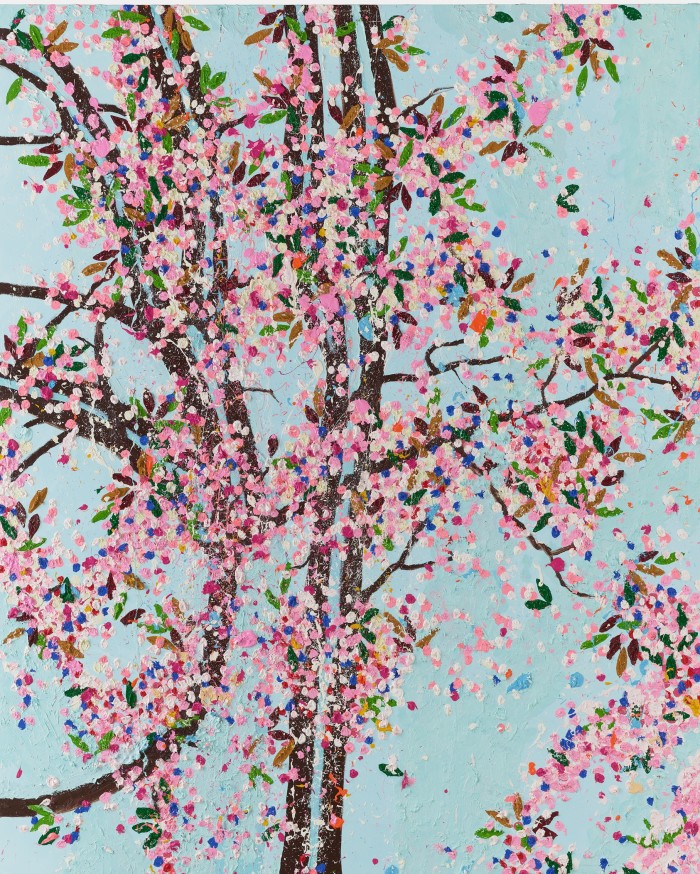

In a sky-high car park in central London, there stands a vast cherry orchard. The petal-laden branches, uprooted from the ground into an abstract canopy of blossom painted on canvas, stand 2... 3… 6m high – a mass of psychedelic pink against the brightest of blue skies. Handpainted by Damien Hirst over three years, they reached their zenith during the past year of working in isolation; this summer a selection of 30 (from the complete series of 107) will move to Paris, to the Fondation Cartier art museum, for a six-month exhibition.

I visited the orchard a day or two before the spring equinox. Central London’s streets were near-deserted, but bulbs and buds of colour were exploding in renegade patches of urban green, and with them the promise of renewal and hope. This only intensified in the hothouse of the studio: “A delirious space of pleasure and fear… that puts the viewer at the centre of a silent but spiralling blizzard of cherry blossoms,” says Japanese art historian Michio Hayashi in the exhibition’s weighty catalogue raisonné. A “coup de foudre” is how Hervé Chandès, director of the Fondation Cartier, describes to me the moment he first stepped into their orbit.

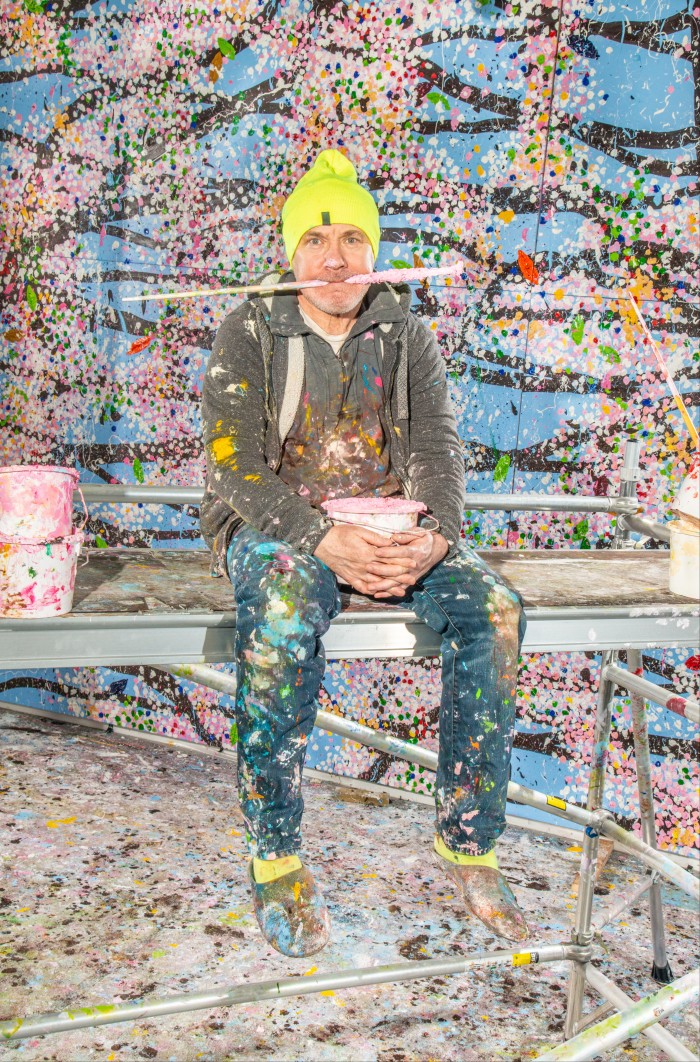

“Coup de foudre?” asks Hirst, when I relay this to him. “I know coup d’état and tour de force, but not coup de foudre,” he laughs. The artist, 55, leans back in his chair; his head, freshly shaven, glows a little pink, and he’s dressed not in the suit and tinted glasses of his enfant terrible days, but in a paint-splattered black shirt and hoodie. A coup de foudre, I say, it’s like falling in love. “I definitely wanted to create an all-enveloping visual experience that just gets hold of you, whether you like it or not,” he replies. “I wanted to bypass all your judgement faculties and just get hold of you, internally. Like, if you walk around a corner… you just go fucking hell. There’s nothing like it, it’s Day-Glo, it’s fluorescent, it’s stupid. It’s chaos in a way that’s violent… it’s a different kind of violence, though.”

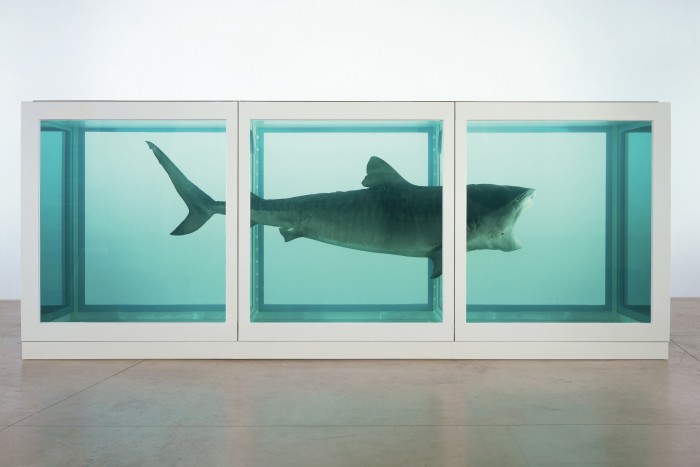

Different from the violent threat of a shark in formaldehyde, for sure – the 1991 piece named The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, which later sold for a reported $12m to US collector Steven A Cohen and made Hirst a household name. Different from the violent separation of 1993’s Mother and Child (Divided), Hirst’s Turner Prize-winning sculpture that sliced a cow and a calf in half, nose to tail, and arranged them in glass vitrines.

Hirst himself seems happy and relaxed. There’s an absence of bombast that seemed to accompany his last epic show, in 2017, Venice’s Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. And if his recent show of monumental outdoor sculpture in St Moritz, his year-long residency at Gagosian gallery (a first for an artist) and his recent announcement of a cryptocurrency art project are examples of his more maverick, showman-like nature, this museum show of paintings reveals another side. “I enjoy his jubilation, his happiness, his freedom,” says Chandès of the mood that shines through the Cherry Blossoms.

“I feel alive when I’m painting them,” says Hirst, matter-of-factly, of his latest series. “So I’m putting my life into it. It’s a lot, you know, of climbing up a ladder, throwing paint, mixing big buckets, chucking them on the canvas from far away – all that energy of life is actually caught in the paint.”

Cherry blossom has long been a subject of fascination for Hirst. When he was three or four and growing up in Leeds, he remembers watching his mother, a shorthand typist, painting a cherry tree in blossom. He drank from a cup filled with white spirit and swirling colours, and became “quite sick”, but the memory of her art, and the intoxicating colours, remains. Later, he became bewitched by a cherry tree outside his bedroom window in Devon. “I realised that, from a time-passing point of view, the tree meant everything to me: that’s another year, that’s another year. For a while, it just became like a clock. And I kind of love it for that reason: all the Japanese significance, the sakura; both optimistic and sad… renewal and death.”

On the one hand, the symbol of the cherry blossom is a “cliché”, says Chandès, or “tacky” says Hirst. On the other, its tension between the fleeting beauty of life, a quick death and the cycle of renewal has a poignancy that “illuminates all Damien’s previous series”, says Chandès. Like Hirst’s dissected animals in formaldehyde, Chandès compares the sensation of being lost within the branches to “an anatomy lesson” within the “interior organs of the tree”.

Hirst himself pins one point of origin within his own Veil series of 2017, which saw him return to painting by hand – his own, as opposed to mechanised dot creations or pieces created by assistants – in a gestural style that drew on abstract expressionism: de Kooning, Pollock, Rothko. The Cherry Blossoms, largely made up of coloured dots that echo the spot paintings, follow the same practice but take the style towards something distinctly representational. Like Veil, they too were also conceived as a finite series – of 90, until working in isolation during the pandemic extended its life by 17.

Hirst has not had an easy ride when it comes to representational paintings. “I think from the very beginning, I’ve always wanted to be a painter,” he says. He cites the colours of Bonnard, the “organised chaos” of Pollock, the scale of the abstract expressionists, the techniques of the pointillists, plus some Hodgkin – even Turner (“though Turner is smaller, but that kind of colour – that’s like a riot”) as inspirations. Yet he reveals a discomfort with the idea – and not a little vulnerability.

“I remember Lucian Freud came up to me at my opening for the Blue Paintings at the Wallace Collection [in 2009],” he recalls of the collection of moody dark pieces that was pretty much universally panned. “He said to me, ‘I didn’t know you could paint.’ And I remember thinking, ‘Is he being sarcastic?’ And then, of course, he’s not, because he’s from that generation and that age. And afterwards, I thought, ‘It’s actually a compliment, you know, it’s not, it’s not a bad thing.’ But I remember I just felt awkward.”

Hence Hirst approached the series with some “fear”. But he overcame it. “What I loved about them [at first] was the way that they were kind of in between representational and abstract,” he says, leaning forward. “I always imagined them looking from underneath, at the canopy; they didn’t have an up or a down. But then towards the end, I started painting the trunk, and they became much more rooted in the ground. And I became happier with them looking a bit more like a tree, which I had been afraid of.” For an artist whose strength is in the conceptual, it’s perhaps easy to see why.

The journey is to some extent emotional as well as stylistic. “Maybe that’s why the trunks became more part of it,” he continues, “because in the beginning of the whole series, I was thinking more about being disconnected from the earth, whereas by the end of it, I wanted to be firmly rooted.” Covid inevitably played its part – but unexpectedly. “This year, I’ve found that I’ve become more accepting of the idea of death, or something, which I never thought would ever happen. I just always thought it was going to be a mystery, but it sort of feels more like a natural part of life to me now than it ever has. I mean, I still don’t want it, nobody wants it, but you kind of go, you know, you’re born, you look around, you die – whereas I used to think you’re born, you look around, it’s a shame you die. Now, I think it makes sense.”

The exhibition is Hirst’s first museum show in France. Chandès, director of the Fondation Cartier since 1994, has made the institution synonymous with a bold programme that mixes the provocative with the ecological and the sensational: from Matthew Barney (in 1995), to Yanomami, Spirit of the Forest (Amazonian shamanism) in 2003. After seeing the cherry-blossom pictures on Hirst’s Instagram in 2019, he arranged through friends to meet him in his studio, fell in love with the “excess of beauty” of the works and offered him a show on the spot.

The show’s catalogue raisonné (€70) is a monumental display of the Fondation’s commitment to the show and its belief in Hirst the painter – full-colour versions of all 107 pieces feature alongside a cherry-blossom cultural anthology and four essays by critics from around the world, hitherto unconnected to Hirst, who set it within a cultural, botanic, and poetic context.

Unlike in Britain, Hirst is a more mysterious figure among French audiences, says Chandès – François Pinault, founder of luxury group Kering and one of Hirst’s biggest collectors, notwithstanding. “Damien is known because his name is big… but he is also unknown because he has not been shown in France. So we talk about what we think he is, his reputation, but we are not talking about the reality of his work.” Chandès is unwavering in his expectations for the show: “The public will be seduced by the paintings.”

And if the $22.4m success of a recent Cherry Blossoms print drop (a sale of $3,000 prints for a limited six-day time period) through Heni Leviathan is anything to go by, they will. Buyers could pay in cryptocurrency – a taster of more crypto japes to come. Soon after, in a move that must sit on the polar opposite end of the spectrum to the cherry blossom paintings, Hirst announced a non-fungible token (NFT) project, The Currency, which plays with ownership, money, exchanges, value systems and the idea of art itself as a currency.

The art world is abuzz with NFTs, the unique crypto- codes for digital artworks (and their alphanumeric tokenised representations) that make the ownership of widely disseminated digital entities possible for the highest bidder. Mere days before Hirst and I speak, Christie’s sold Beeple’s digital artwork The First 5,000 Days to the blockchain entrepreneur/NFT collector known as “MetaKovan” for $69.3m in cryptocurrency. And days after the interview, Hirst announces that his blockchain-linked paintings for The Currency will be available to buy on Palm, a new, energy-efficient NFT platform. Hirst is captivated by the outrage and disruption: “A lot of people are worried it’s the end of the galleries. I think there’s always a place for all this stuff. It’s just a really exciting new realm... it feels hugely important. I just don’t know where it’ll lead.” But there is, he concedes, a parallel with the old systems: “We wouldn’t have museums if people didn’t own paintings and then bequeath them. And it’s the same thing with NFTs. I get comfort from it... I like that [digital art] can be reproduced, but you own it, because you’ve got the code.”

It turns out that Hirst’s 15-year-old son, the youngest of three, introduced his dad to Beeple a few years ago. He liked what he saw. “I was thinking I should talk to this guy; I should get him to make these images on canvas, and I should offer him a show at Newport Street [where Hirst has a gallery],” says Hirst. “Now, I look at it, I’m like, holy shit… there was just no need for that. It’s something else. There’s no need for the conventional way. It’s just another way.”

For now, though, there’s the small matter of a big museum show of IRL paintings. Old-fashioned, anachronistic, maybe. But in the words of his fellow artist David Hockney, “You can’t cancel spring” – no matter how many blockchains and non-fungibles you throw at it. “If you like art, if you like colour, if you like painting, it’s pretty hard not to like the paintings, I would hope,” concludes Hirst.

Cherry Blossoms runs from 6 July to 2 January at Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, 261 Boulevard Raspail, 75014 Paris; fondationcartier.com

Hirst’s hits

1986 to date

Spot paintings

Hirst’s multicoloured spot pictures

1988

Curated the student show Freeze

Included Mat Collishaw, Ian Davenport, Anya Gallaccio, Gary Hume, Sarah Lucas and Fiona Rae

1991

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living

4m tiger shark in formaldehyde

1993

Mother and Child (Divided)

Turner Prize-winning sculpture featuring a cow and calf split lengthways.

2007

For the Love of God

$50m platinum skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds made by Mayfair jeweller Bentley & Skinner

2012

Tate Modern retrospective

2015

Newport Street Gallery

Hirst opens his own gallery in Vauxhall, south London

2017

Veil paintings

A return to painting by hand, in abstract expressionist style

2021

Cherry Blossoms, Fondation Cartier pour L’Art Contemporain, Paris

Comments