How sprawling suburbs are stunting productivity in UK cities

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Leeds and Marseille. It is a tale of two cities — or, more broadly, the story of why continental European cities are healthier and wealthier than their British counterparts and what needs to be done to close the gap between the two.

It begins in Leeds, where Matt Saunders, a 37-year-old business coach, stands waiting for the number 49 bus to take him to work. It arrives eight minutes late and takes nearly 45 minutes to reach his city-centre office, crawling slowly through thick lines of traffic.

Matt recently moved out of his rented central flat, buying a semi-detached house with his partner, Liz, in the city’s upmarket north-eastern suburbs.

They would “love to be able to live without a car”, but after just a few months struggling to use Leeds’s fragmented bus network to see friends and go shopping with their new baby in tow, they reluctantly decided that it was unavoidable.

The configuration of Matt and Liz’s suburban life is typical of millions of British city dwellers, but it contrasts sharply with people living in similar-sized cities in continental Europe, according to a report by the Centre for Cities, a think-tank.

Researchers found that Britain’s sprawling suburbs of low-density housing, often poorly connected to city centres by weak transport links, were a key reason why British cities are less productive and pleasant places to live than their European mainland equivalents.

Narrowing that divide should be an essential part of prime minister Boris Johnson’s plans — due to be formally laid out in a government white paper in the coming months — to “level up” areas outside London and arresting a decade of UK productivity declines, says Andrew Carter, the think-tank’s chief executive.

And building better transport networks for the millions of commuters, while essential, will not be enough. To truly make the difference, UK cities must become more densely populated, just like their EU counterparts, he explained.

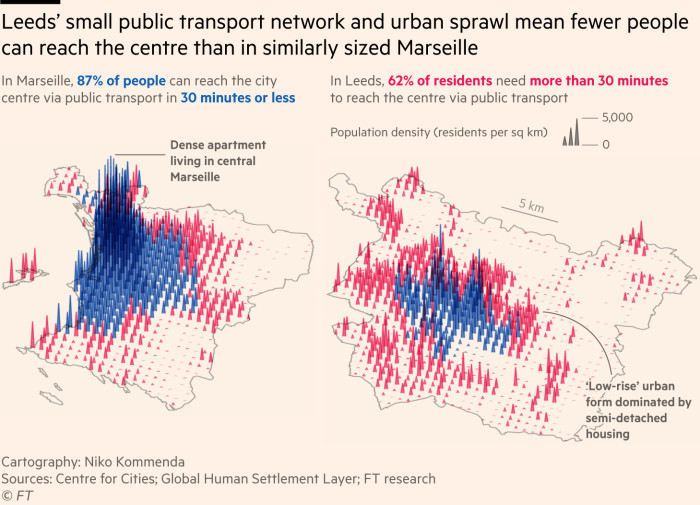

To illustrate the point, the Centre for Cities compared Leeds, a city of approximately 800,000 people that has no mass transit network, with the similar-sized French city of Marseille, which has a 32-station tram system that opened in 2007.

They found that in Marseille 87 per cent of residents could reach the city centre in 30 minutes by public transport, compared with only 38 per cent in Leeds.

But, tellingly, even if Leeds was magically blessed overnight with Marseille’s tram system, the number of people able to get into town at speed would only climb to 61 per cent.

“The point is that transport is not enough,” says Carter. “You are still going to need to encourage cities like Leeds to build a lot more houses in the city centre.”

In Marseille, Saadia Osmani, a 44-year-old adult-education teacher, recalls a past that is almost the reverse experience of Matt and Liz.

For several years she lived on the very outskirts with her son and daughter, Noé and Suzanne, now 14 and 11, became disillusioned with the long commute and moved back into the city in 2013.

Now she lives in a typical six-storey townhouse in Marseille’s fourth arrondissement. She is five minutes’ walk from the tram stop that takes her to work in the city centre’s Lycée Thiers, with the journey taking 20 minutes door to door. The children can walk to school in 12 minutes.

“I would never move out again,” says Osmani. “I have everything I need nearby. If I need to see friends, I can just walk. We have cafés, restaurants, a park, a museum and two open-air markets.”

Making UK cities more effective

The Leeds-Marseille comparison is striking but not unique. The story it tells is emblematic of the challenge of urban regeneration in Britain when compared with continental Europe, says Carter.

Overall, the Centre for Cities calculated that, on average, just 40 per cent of the population of big British cities is able to reach the city centre by public transport in 30 minutes, compared with 67 per cent in mainland European cities.

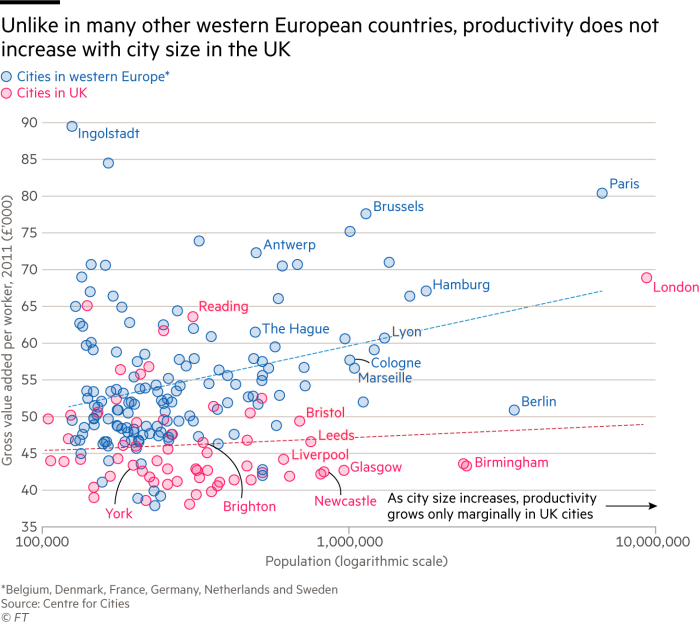

Having more accessible cities is a major driver of productivity, adds Tom Forth, chief technology officer at The Data City, a consultancy that maps emerging urban economies.

Better transport and housing create natural clusters of creativity, enabling employers better access to the skills and workers they need to expand the businesses, “agglomerating” the talent that drives innovation, he adds.

“Agglomeration matters. So areas like Canary Wharf or La La Défense in Paris are important because they bring people with similar skills and interests together, and keep them together. So, basically, Apple being close to Google is a ‘good thing’,” he explains.

The prospect of increased hybrid working, involving the home as well as the office, after the coronavirus crisis is not expected to fundamentally change the need for agglomeration of talent in city centres, said Anthony Breach, co-author of the Centre for Cities report.

“Even if some people shift to working from home permanently, city centres, and access to them by public transport, will remain vital to urban economies,” he added.

Measured by their “effective size”, based on the number of people who can actually reach the city centre by public transport in 30 minutes, the “effective” population of many large UK cities is far smaller than the headline population numbers suggest.

The Centre for Cities calculated that Rome, a city the same size as Manchester, was “55 per cent more productive” than its British counterpart, in part because it is able to get a much larger share of its workforce into the city centre by public transport.

Increasing Manchester’s “effective size” from about 490,000 to 1.3m people through better transport networks and denser housing could improve productivity by 15 per cent, the report found.

In total, increasing the “effective” size of big cities to continental European levels could create benefits to the UK economy worth more than £23bn a year.

The mid-rise neighbourhoods inhabited by Saadia Osmani and millions of city dwellers in continental Europe are also more carbon-efficient, meaning lower heating bills and a reduced carbon footprint. Denser neighbourhoods with more people, also sustain better shops, cafés and other amenities.

“If an individual lives in medium-density housing in the centre of town with a tram network, they’re less likely to need a car, which means less congestion and better air quality,” adds Carter.

Fixing the future

Narrowing the gap between British and mainland European cities will simultaneously require both investment in transport and moves to repopulate UK city centres, which emptied out into the suburbs during the course of the 20th century.

In the case of Leeds, that means finally building a mass urban transit system to rival the likes of Marseille after two previous proposals — a supertram scheme in 2005 and a trolleybus system in 2016 — were both cancelled.

The process is beginning. The city was granted £100m to begin development of a mass transit system in the £96bn integrated rail plan released last month which saw the scrapping of the Leeds leg of the flagship HS2 high-speed rail line from Birmingham.

Martin Farrington, director of development for Leeds city council, says this £100m “consolation prize” should mean the first leg of a new mass transit system for Leeds opening “in the next six or seven years”, or at least by the end of the decade.

In the interim, adds James Lewis, Leeds city council leader, the situation could be improved by speeding up government plans to bring regional city bus networks back under local government, allowing local franchise operators to be brought into a single system.

Currently, in Leeds, passengers must choose between competing companies — Arriva, First, Stagecoach, Transdev and Yorkshire Tiger — with different ticketing systems that require travellers to have different apps on their phones to use different buses.

Lewis says the aim would be to create an “Oyster-style” single ticketing system for Leeds’s bus network, like the system enjoyed by commuters across London who can access underground trains and buses with one payment card.

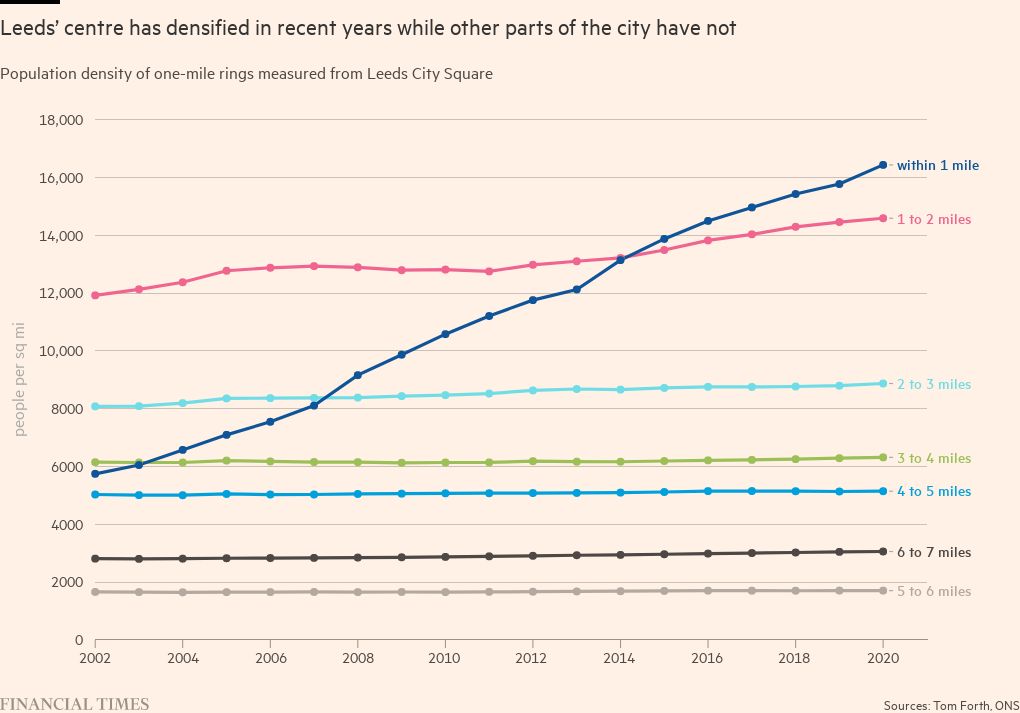

The process of creating a more densely populated city centre has also begun, says Farrington, with 4,000 flats and houses already under construction and possible plans for a total of 18,000 more by 2033.

Data from Forth at The Data City show that within a two-mile radius of the Leeds centre, population density has more than tripled during the past 20 years, creating a potential nucleus for a city that is becoming increasingly dynamic.

Lewis cites the example of Channel 4, the television company, that this year opened its new headquarters in Leeds, and the decision by the Bank of England to make Leeds the site of a new northern hub.

But such developments will need an urban environment that attracts and retains talent in order to thrive, says Forth. “Better cities lead to greater retention of skills,” he adds. “Hull should be the equal of Rotterdam, but I’ve been to Rotterdam and I can tell you, it’s not like Hull.”

And there are early signs of change. Farrington cites the example of Citu, a medium-density development of carbon-neutral homes around Leeds Dock that has a primary school and is built around the concept of a “20-minute neighbourhood”. It already has 15 families with young children.

“It’s a bit of ‘chicken and the egg’,” he says, “You can’t attract families without a school, but you can’t build a school without families, but it will come. Services will catch up. In 10 years’ time you’ll find a lot more residential development in the city centre. And I can say that with confidence because it’s happening right now.”

For Saunders, the transformation is not yet sufficient to tempt him back from the suburbs. He values a sense of community from settling in a neighbourhood, in contrast to the centre, where residents are younger, creating a high turnover of neighbours.

But peering down on Leeds from his 17th-floor office, looking out over the closed premises of Debenhams, the now-defunct department store, Saunders says he could one day see himself embracing a new vision for city-centre living.

“If the city was more than a place where you came in to work or spend money in the shops and then leave, then yes, I’d love that,” he says.

Data and visual journalism by Niko Kommenda

Comments