Love Lee Miller? Here are a bundle of reasons to fall for the photographer again

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

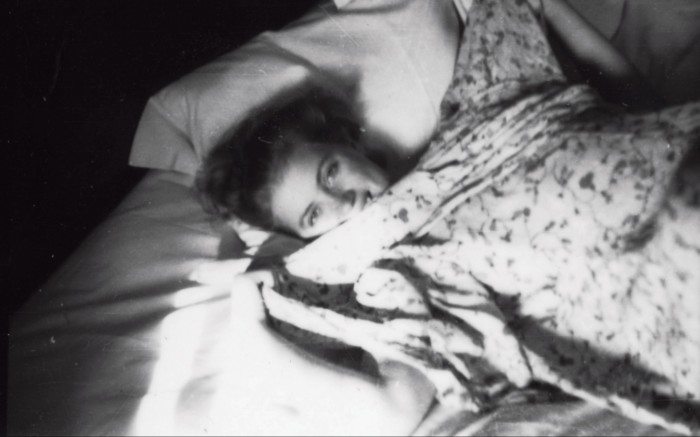

As a child, I was often at Farleys, the East Sussex farmhouse belonging to my grandparents Lee Miller and Roland Penrose. Lee had died in 1977, the year I was born, but not long after, her photographs, negatives and manuscripts were found stashed away in the attic by my parents. At the time, she was celebrated as a gourmet cook and had never spoken of her earlier career as a photographer and war correspondent to my father, Antony Penrose. The discovery spurred him into wanting to know who his mother really was, and with the support of Roland they started to create an archive.

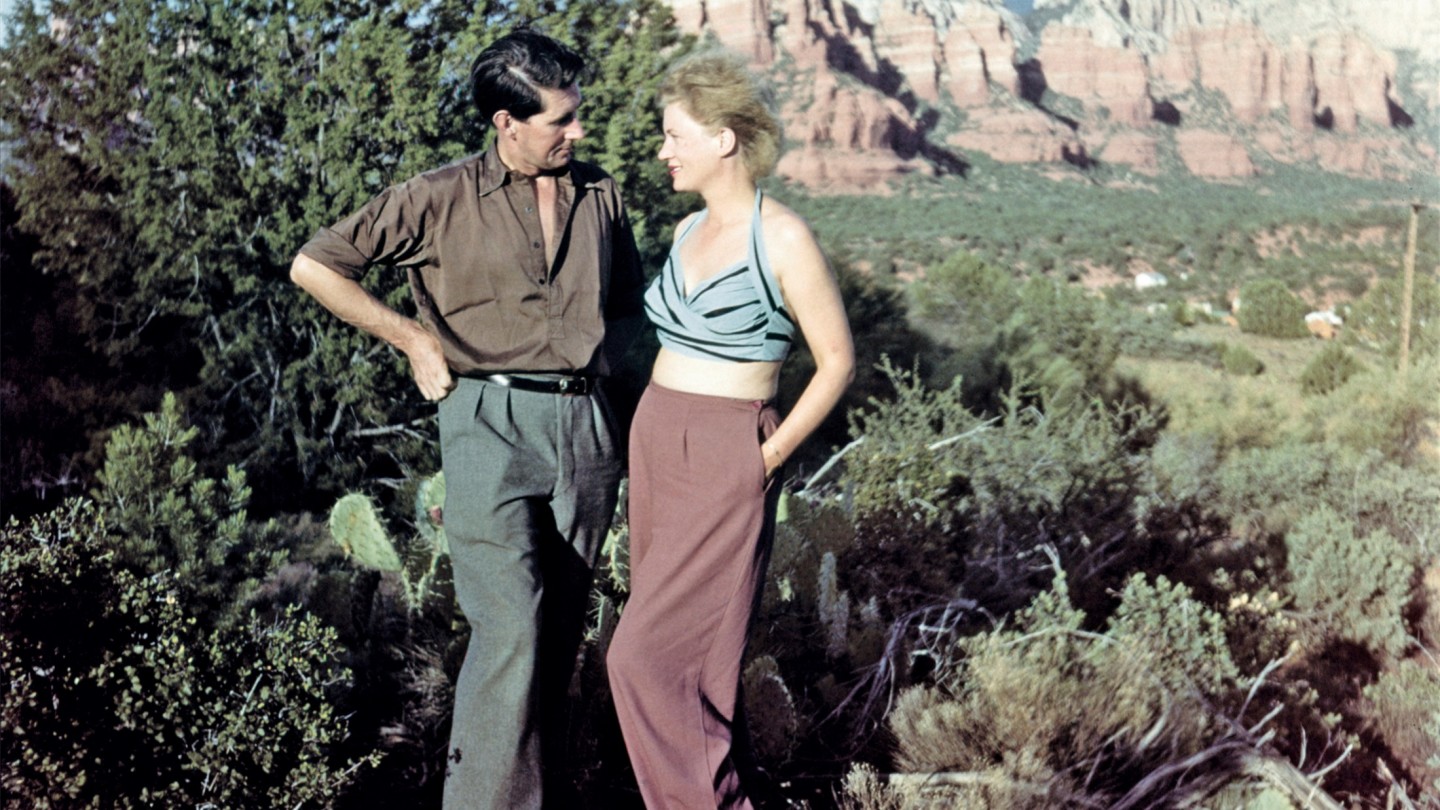

It took 10 years to sort through the jumbled mess, and contact print the 60,000 negatives – most of which was done in our house as I was growing up. And as their dedication revealed more of her extraordinary talent – stylish and surreal pictures from her successful commercial studios in Paris and New York from 1929 to 1934, fashion photography for the likes of Vogue and her war-correspondent work – the world started to remember Lee Miller alongside us. My sister and I thought it so normal to go to openings that we invented a game in which we’d make exhibitions of our puzzles for our parents to walk around, as if in a gallery.

But it wasn’t until I started to help out in the archives in my 20s that I myself made a discovery: the richness of Lee’s letters and manuscripts, which had mostly been eclipsed by the photographs and negatives.

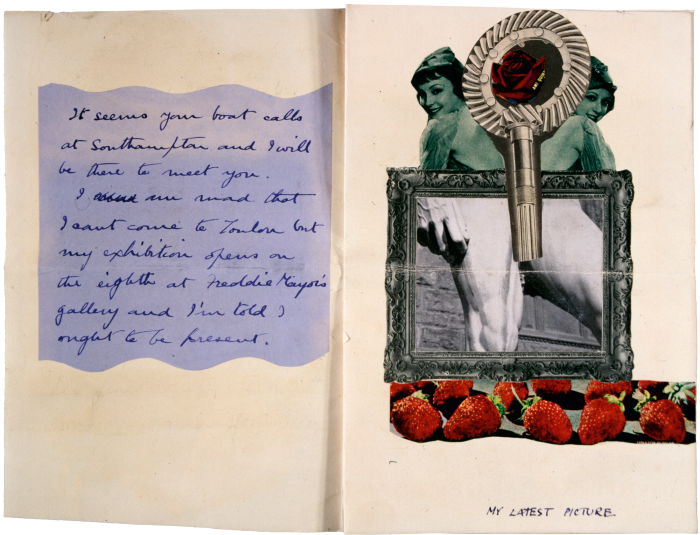

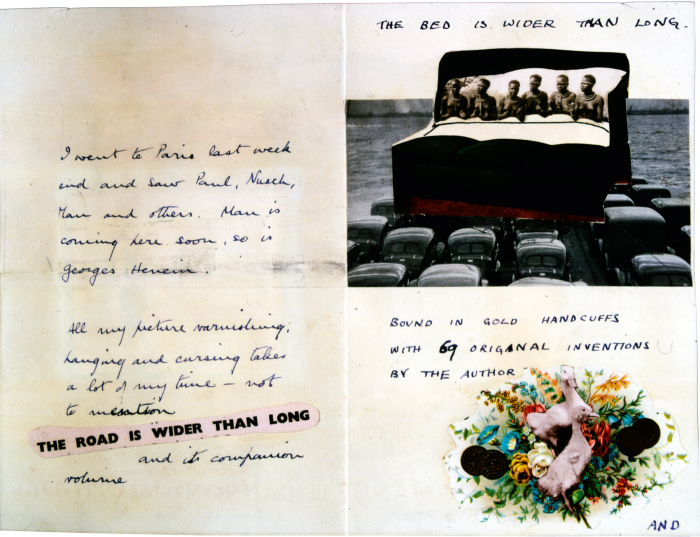

Reading Lee’s personal and intimate letters – to Roland, but also colleagues at Vogue; her family; and her first husband Aziz Eloui Bey, all signed Love Lee – offered insight into a different side to her. Lee was very well read, which is surprising considering the number of times she was expelled from school, and she describes things vividly, writes intelligently, and with honesty, raw emotion and humour. Some are handwritten in her distinctive joining curls, but the majority are typed – her typewriter had quite a character, often deciding to write in red or insert £ signs or other symbols in the text. (Roland wrote to her in one of his early love letters: “Incidentally, your typewriter is a very charming machine since it conveys as much temperament as any pen with its flights into £££ and its very original type, which I like reading for more reasons than one.”) We also found letters written to Lee from artists including Edward Steichen, Man Ray and Joseph Cornell, as well as some inscribed artworks from Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso and Dorothea Tanning. Many still have their envelopes with their beautiful stamps.

We decided to launch the LoveLee Letters Membership. In part, the idea came from our desire to share Lee’s letters with more people. But also, the pandemic has shown us the vulnerability of our quest to conserve the legacies of Lee and Roland, and to share the gems from the archive. Until last year, we relied on international exhibitions, rights sales and opening Farleys House & Gallery to the public to support our activities. It worked well until our income was decimated in the wake of Covid-19. In order to avoid permanent closure, we launched a Crowdfunder campaign, which has sustained us through the winter, and had a grant from the Culture Recovery Fund, awarded by the Arts Council England. But it’s not enough: the LoveLee Membership is a new, longstanding way to help support Farleys House and the Lee Miller Archives.

The membership is an inclusive one (from £3 to £175 plus VAT per month). Short videos explore stories and themes around Farleys, the collection and Lee and Roland. Podcasts feature readings of the letters. Platinum membership includes an annual behind-the-scenes private tour of Farleys and the archives.

For the podcast, an actor and I have read the love letters written between Lee and my grandfather Roland between 1937 and 1939. Each kept the other’s letters, so you can hear their love story developing from both sides. They talk of their travels, other surrealist artists and their role in the art world – all set against the backdrop of the build up to the second world war. It’s wonderful to hear them talk (and occasionally gossip) about famous artists they called friends, including Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst and Man Ray, and about world events as they unravelled. Ultimately, it’s a story of two young surrealists exploring the world.

The membership is called LoveLee for several reasons, the obvious being that it is how Lee signed her letters. But because of the double meaning, it could also mean that members are “lovely” for supporting her archive, or are people who “love Lee” Miller. Wordplay like this was something that the surrealists loved to explore, and Lee used with some of her picture captioning. And it would be lovely if it opens a new chapter on a legacy that was so very nearly forgotten.

How to give it

Patreon patreon.com/leemillerarchives

Farleys House & Gallery farleyshouseandgallery.co.uk

Lee Miller Archives leemiller.co.uk

Comments