Students lose faith in professional disciplines

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Zachary Zimmern knows the value of a legal education. He can count it in dollars spent on tuition and in the number of interviews he was able to obtain after graduation from Brooklyn Law School in June 2012. Comparing the two gives a picture of the state of legal education and the job market for new lawyers in the US.

“I graduated unemployed. I couldn’t find anything,” he explains in a soft New York accent. “I didn’t really find a job until nine months after I graduated, and even then it was a job that I was unhappy with.”

Still, when he compares himself with his classmates, he says he feels like “one of the lucky ones”.

According to statistics from the National Association for Law Placement (NALP), the employment rate for law school graduates has fallen for six years straight. Overall, figures are still high at 84.5 per cent, but they must be weighed against the average debt level of recent graduates — which is around $125,000 for those from private law schools.

This includes Mr Zimmern, who had to move in with his parents during the job hunt to cut his expenses. “The stress level was severe,” he recalls.

At a time when those newly admitted to the bar are struggling to find employment, one might expect to see a shift in applications to other graduate programmes, most notably MBAs, which often attract students with similar profiles and budgets.

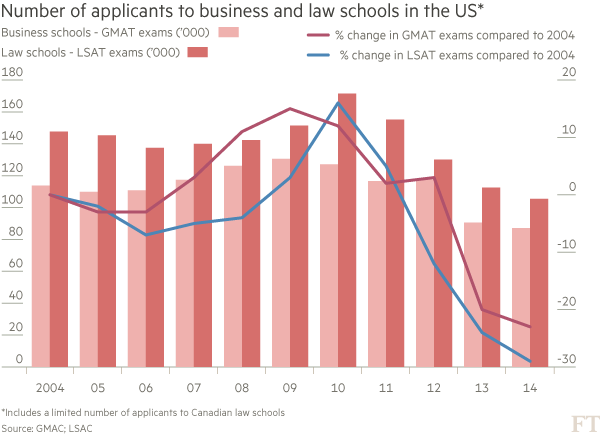

However, there has been a decline in applications to both MBA programmes and law schools in recent years, seemingly for different reasons.

The two can be difficult to compare, given that the latter is required for legal practice while the former is not required for business. But their application trends have several similarities, both in their flat or negative growth and in the enduring strength of the most prestigious schools.

The number of US citizens taking the GMAT, the entry test for business school, fell to approximately 87,000 last year, down from 127,000 in 2010.

Data from AACSB International, a business education membership and accreditation organisation, show admissions dropped almost 14 per cent over this period.

As one might expect, not all schools are suffering equally. Applications to MBA programmes at top business schools are actually rising as part of a flight to quality. Schools such as Harvard, Stanford and Chicago Booth have therefore been able to become choosier about their entrants, just as top law schools (often at the same universities) have also had fewer difficulties.

As Dan LeClair, chief operating officer of AACSB, says: “In a world like the one we’re in right now, brand does matter.”

But while the decline in applications to law schools appears to have a direct connection to the market for graduates, the roots of the downward trend in MBA applications are less clear.

Data from GMAC show that job opportunities for MBAs remain favourable. But Mr LeClair is quick to note that business education is less monolithic than legal study. Specialised masters operate alongside MBA programmes, giving students a greater diversity of options to choose from.

“The numbers for other masters degrees are pretty strong,” he observes. “Overall, at the masters level we have seen an increase of about 11 per cent over the last four or five years.”

At law schools, it seems to be all about the lack of jobs. According to Wendy Margolis of the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), prospective students are increasingly aware of the struggles in the graduate job market. “The word is out that going into heavy debt for law school is not as sure a bet for a secure future as it once was,” she says.

In particular, Ms Margolis explains, it is becoming difficult for graduates to find positions that allow them to meet student loan repayment schedules.

“There are still many areas of employment for lawyers in the US, but not all of them generate high enough salaries.”

According to statistics prepared by NALP, the median starting salary for law firm employees has fallen dramatically since the financial crisis. Although it has recently risen slightly to $95,000, it is still $35,000 short of reported figures for 2009.

This “softness in the job market” — as Barry Currier, managing director of accreditation and legal education at the American Bar Association (ABA), describes it — has coincided with, if not directly caused, a sharp fall in application numbers. As of March 6, the LSAC reported that applications are down 6.5 per cent from the same period in 2014. Total end-of-year application numbers have fallen by more than 6 per cent every year since 2011.

It is a trend that is starting to strain the finances of once-secure law schools. Brian Leiter, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, has predicted we could soon see the collapse of certain schools accredited by the ABA.

Mr Currier stresses that schools are cutting costs as they “adjust their behaviour to the market”. Still, he admits, those that fail to adapt “may have some issues”.

That these upheavals are affecting law degrees and MBAs, two qualifications that have long been seen as safe choices for aspiring students, demonstrates the extent of the reshuffle that is taking place in American graduate education. Just where those would-be law and business school students will go instead is uncertain.

Comments