Preferred Networks teaches robots to collaborate through deep learning

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Junichi Hasegawa of Sony first met the two young creators of Preferred Networks, there was something familiar about them. They each possessed, in his view, the spark and talent of Akio Morita and Masaru Ibuka, the founders of Sony itself.

Shortly afterwards, in 2011, Hasegawa, who was in the team developing the PlayStation games console, opted to join the tiny start-up that later became Preferred Networks. Sony was languishing under heavy losses from its once-mighty consumer electronics products and Hasegawa had the opportunity to move on. “Instead of rebuilding Sony, I felt it was faster to build a second Sony,” he says.

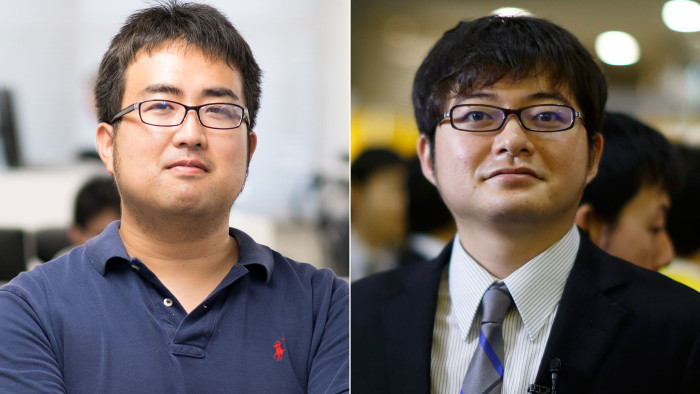

In a business culture where many people regard their employer as one for life, it was a bold career move. Few outside the computer programming world knew about Toru Nishikawa and Daisuke Okanohara, Preferred’s founders. The two had met at the University of Tokyo and excelled at writing software for data and image analysis — but they were programmers and knew little about running a business.

“We were engineers, so we knew what products we wanted to make but didn’t know how to sell them,” Nishikawa recalls of the early days of the business. “Money was the biggest problem for us in the beginning.”

Hasegawa’s decision to quit Sony proved to be a shrewd one. He went on to become Preferred’s chief operating officer. Nishikawa and Okanohara’s company focuses on a new field in artificial intelligence (AI) called deep learning. The technique is modelled on how the human brain works and has led to groundbreaking advances in computers’ language understanding and image recognition. What sets this Tokyo-based business apart is its distinctive approach to applying deep learning to the internet of things (IoT).

Preferred rapidly became one of the country’s most high-profile start-ups after attracting $20m in funds from big Japanese groups, including carmaker Toyota, communications group NTT and robots specialist Fanuc. Toyota put the company’s value at $300m at the end of 2015 when it formed its tie-up with Preferred in AI and self-driving technology.

Nishikawa, now Preferred’s chief executive, knew that a 60-employee operation could not compete with the likes of Google, Facebook and Amazon which can call on huge troves of data to train their systems — for example, to understand language.

Instead, Preferred has focused on collecting data generated by big manufacturers’ products such as cars and industrial robots.

This makes Toyota, the world’s second-largest carmaker, and Fanuc, whose distinctive yellow robots operate in factories worldwide — including those of General Motors, Volkswagen and Tesla — natural partners for Preferred. The key, the company’s executives argue, is to form a partnership with the global industry leader in any particular field.

This plays to Japanese strengths. If Silicon Valley is the leader in software, Japan remains at the forefront of manufacturing, producing key electronics components and robotic tools used in the making of global bestsellers such as Apple’s iPhone.

“Deep learning has just started to gather speed and worldwide efforts to apply that technology to IoT have just begun,” Nishikawa says. “If we could combine them with areas where Japan is way ahead, I thought we had a chance to win.”

For Nishikawa, it was a visit in spring 2015 to Fanuc’s factory, nestled in a forest at the foot of Mount Fuji, that convinced him that manufacturing would be the core area in which to apply Preferred Networks’ expertise in deep learning.

Fanuc’s robots are built around the clock by armies of other robots. The machines doing the manufacturing are overseen by fewer than five people on standby for maintenance and are monitored remotely by a handful of others.

“What I witnessed was robots making other robots without human intervention,” Nishikawa says. “If you keep the robots operating, data can be collected infinitely.” Despite the factory being so advanced, however, he notes that “AI technology was not used anywhere and I felt there was a big opportunity here”.

Soon after Nishikawa’s visit to its factory, Fanuc took a 6 per cent stake in Preferred for $7.9m. Then, in 2016, Fanuc announced that it had teamed up with Preferred, California-based IT multinational Cisco and US factory automation systems maker Rockwell Automation to offer a new service connecting its robots to make them more intelligent.

The service uses another core feature of Preferred’s technology — edge-heavy computing — which the company hopes will give it a competitive lead over AI rivals. Edge-heavy computing allows data to be processed closer to where the data are coming from instead of storing everything in the cloud, which has drawbacks in terms of speed and security.

In Fanuc’s case, the system envisions placing the data on a device that can be installed at factories and connected to existing equipment and even robots made by rivals. By eliminating the need to transfer massive quantities of information to remote data centres, it also makes it easier to determine which data are relevant and which information should be shared with other robots.

The system’s users will eventually be able to download applications that match their factory needs — in a similar fashion to accessing an app store on a smartphone. By applying Preferred’s AI technology, the robots will learn to share and analyse data, and collaborate to detect glitches that might interrupt production.

Nishikawa forecasts that within two or three years robots will have learnt to collaborate with each other, but there will continue to be tasks that humans are more suited to or can do more cheaply than expensive sophisticated robots. For example, to pick up things that are scattered about randomly, a robotic hand would need to be installed with a significant number of expensive sensors, whereas humans use their natural instinct to instantly find the fastest way to do the job.

“There will be a greater distinction between what the machines are good at and what humans are good at, so the important thing is to find how they can collaborate,” Nishikawa says. “I believe the key to [that] will be the ability of robots to understand human words.”

Developing deep learning technologies and new software will require substantial investment, especially as the company seeks to expand its application beyond manufacturing and robots to biotechnology.

Nishikawa says he is not worried for the time being about the resources this will require. Preferred continues to receive a wide range of investment offers from carmakers and robot manufacturers around the world, allowing it to be selective about business partners. The company does not want to cede management control and has rejected takeover offers in the past, although executives have not yet laid out any plans to list its shares. “We joined this company because it’s fun to watch what kind of a new future these two [Nishikawa and Okanohara] will create,” says Hasegawa.

“Nishikawa thinks of crazy ideas and aims for bizarre things because he is not restrained by past experience,” he adds. “It will be dull for everyone if the company is controlled by our investors.”

Preferred’s employees, who are still mostly in their 20s or 30s, carry an air of confidence. But when Nishikawa and Okanohara were thinking of pivoting their entire business on deep learning, the industry was just waking up to the technology’s potential and both were unsure they were making the right decision. The man they turned to in 2011 was Ken Kutaragi, now 66, the former head of Sony Computer Entertainment and best known as “the father of PlayStation”.

“When I asked them what they wanted to do, they said they had several ideas but they had not set their minds,” recalls Kutaragi, who set up his own technology start-up after leaving Sony in 2007. “So I told them that you have to do something that would change the world. You have to be a gambler and be ambitious if you want to [build] your own business.”

Six years on, Preferred’s two founders are no longer in doubt about where the pillar of their business should be. Their ambitions have grown: they want to create a technology in computing that society feels it cannot live without — just like innovations from Microsoft, Apple and Google.

The future of Preferred Networks is in many ways a test case for Japan’s generally lacklustre start-up scene. Graduates still tend to take the safer option of joining big conglomerates, rather than participating in new businesses.

Nishikawa feels the challenge of attracting and keeping the people it wants could be the most serious risk Preferred faces. “In order to fight with the strong global players in deep learning and IT, we need to have a strong team,” he says. “The biggest threat for us is losing our talent.”

Comments