Working but homeless: a tale from England’s housing crisis

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ryan Russell pokes his head into a small, warm room with clean white walls and a single bed next to the window. “Is this mine?” he asks. Outside, the rooftops of the affluent English town of Tunbridge Wells, 45 miles south of London, are washed in pale winter sunlight.

The lanky 22-year-old sits on the bed, which suddenly looks too small for him, a big grin spreading across his face. Will his feet poke out of the end? “I’ll be fine, I’m only six foot five!” In the room across the corridor, Josh Chantler, who is 23 but seems older, stands by the window and looks quietly at the view.

For both men, who have been living at the YMCA hostel for young homeless people in Tunbridge Wells, this is their new home. They will have some unusual housemates.

Habitat for Humanity, the Financial Times’s seasonal appeal charity this year, has converted a large old Quaker meeting house: the Quakers have kept the front section, and nine young homeless people from the YMCA will move into three shared flats in the rest of the building.

“The amount of reassurance we had to give the Quakers that these guys wouldn’t disturb them for an hour-and-a-half on Sunday morning,” says Gareth Hepworth, chief executive of Habitat for Humanity’s British operation. “As if we’d be up!” quips Mr Chantler.

The story of how these young men have ended up here — and why this project even exists — tells a bigger story about the rise of homelessness in England, even in the middle of a jobs boom.

Royal Tunbridge Wells is a town of honey-coloured stone buildings, brasseries, tailors and delicatessens. With good schools, surrounding countryside and a 45-minute train ride to London, it is popular with professionals who commute to the city. Estate agent windows are full of pictures of beautiful homes at eye-popping prices. “Fascinating, aren’t they, even if you can’t buy them!” says a woman waiting for the bus.

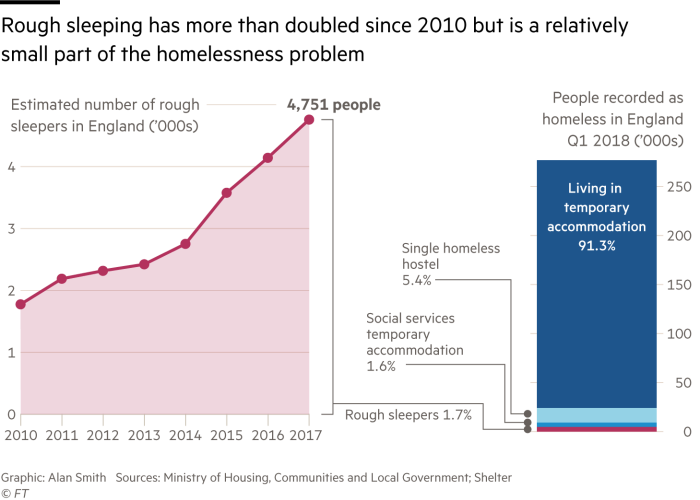

But the number of people sleeping rough, often in the doorways of these glossy shops, has doubled since 2010 across Tunbridge Wells and the neighbouring two local authorities, according to official numbers. That is mirrored in the national statistics. England is witnessing the biggest sustained rise in rough sleeping since the 1990s — almost 5,000 people, based on official counts, though homelessness organisations say that is an underestimate. Rough sleepers are only a sliver of the problem. For every one person in a doorway, there are another 57 out of sight, sleeping on the sofas of friends, in hostels or in temporary accommodation.

The total homeless population of England, according to the housing charity Shelter, is about 277,000, the equivalent of a medium-sized English city such as Brighton.

This rise in homelessness has coincided with an economic “jobs miracle” in Britain that has pushed unemployment down to the lowest since the 1970s. In Tunbridge Wells, just 0.8 per cent of the population are claiming jobless benefits, compared with 2.3 per cent nationally. A group of churches in the town takes turns each night to provide homeless people with shelter through the worst winter months.

But Reverend Canon Jim Stewart, who runs the project, says they quickly realised they needed to adjust their arrangements because so many homeless people were working. Their cut-off time was 8pm, but people with jobs in pubs and restaurants would not finish their shifts until later. Similarly, some people needed to have breakfast early to arrive for their morning shifts on time.

“Some of them clock up significant hours, which makes it all the more distressing that they get to the end of the day and they don’t have anywhere to call their own,” he says. Mr Russell, who has just started a full-time job in a meat packing factory, says the YMCA is quiet during the day because people are out at work. “It used to be more than 95 per cent of the place didn’t work, and they were all on benefits, but now, it’s probably only say 10, 15 per cent, maybe less.”

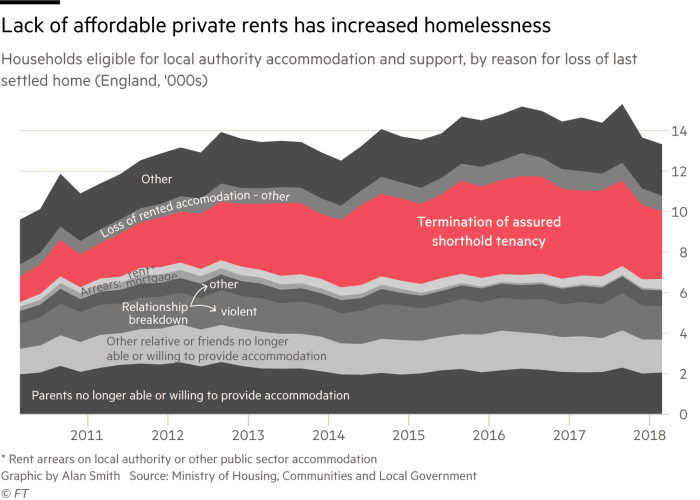

Whatever is going wrong, a buoyant jobs market has not been enough to fix it. The biggest problem is the country’s housing market. There is a shortage of affordable homes for people on lower incomes, particularly in London and the south-east. Council-owned flats and houses used to serve this purpose, rented to people at “social rents” below market rates. But the Right to Buy policy in the 1980s, which allowed council tenants to purchase their own homes at discounts, reduced the number of properties available to lower income tenants, and new building has not kept pace with demand.

Tunbridge Wells, which sold all its council homes to a housing association in the 1990s, is a good example. There are now about 1,000 people queueing on the town’s housing register for a home, who cannot afford to buy or rent in the open market. That number is not going down. The housing association and private developers are building homes, but not enough of them. The council calculates the town needs 341 new affordable homes every year, but for the past five years it has averaged about 100.

Building in Tunbridge Wells is constrained by the “greenbelt”, a policy to protect the countryside from urban sprawl. Housing associations also have financial constraints, and recent national policy has encouraged them to focus more on building homes for ownership than rent.

That has pushed more and more people into the only option that remains: the private rental sector. Nearly 40 per cent of 25-to-34-year-olds now live in private rented accommodation, compared with 12 per cent in the mid-1990s. During that same period, average rents have risen 53 per cent in real terms in London, and 29 per cent across the rest of Britain, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies think-tank.

The most common cause of homelessness now, in Tunbridge Wells and nationally, is losing a private tenancy, either because people fall behind on the rent, or because the landlord sells the flat and they cannot find anywhere else they can afford. Housing benefit is meant to help, but, because so many more people are living in the private sector, an increasing amount of taxpayers’ money has been flowing to private landlords.

In 2011, the government was desperate to curb the £25bn-a-year bill. It implemented reforms that reduced the generosity of housing benefit and detached it from the growth in market rents. The cuts have saved about £3bn a year, but put low-income tenants under more pressure from rising rents.

“There isn’t enough social housing, therefore more people are in privately rented homes and the housing benefit doesn’t cover it,” says Matthew Downie, policy director at homelessness charity Crisis. “If you were to invent a system to create homelessness, this is the way you would do it.”

In the housing team’s office at Tunbridge Wells Borough Council, an inflatable reindeer sits at an empty desk. “It’s nice to have a bit of Christmas cheer,” says Sarah Lewis, housing register and development manager. She and her team are confronted daily with the problem of finding people places to live in an expensive town.

The West Kent Homelessness Strategy for 2016 to 2021, written jointly by the local councils, puts it starkly. “We anticipate that there will be a marginal group of low to middle income households who are unable to access any of the home ownership products, who are priced out of the private or affordable rented sector and who have no realistic hope of being allocated social housing,” it says. “Dealing with the needs of this group will be one of the main challenges for us in the coming years.”

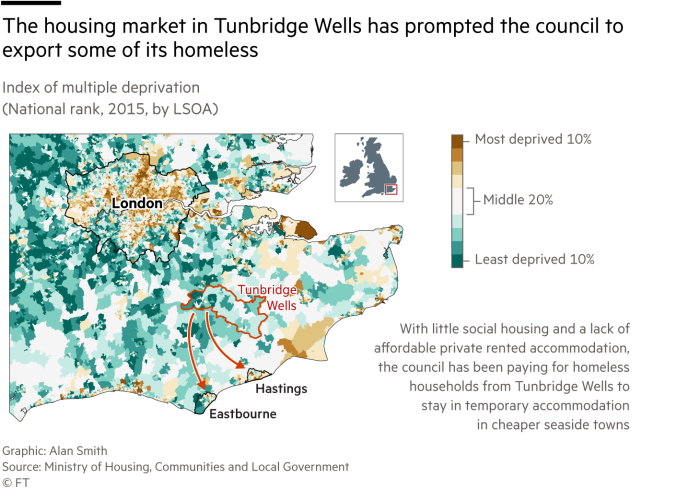

The council has had to innovate. Its most immediate problem is where to put the subset of homeless people that it is legally obliged to house, such as pregnant women and families with children. With no space in the town, the council has been paying for them to stay in temporary self-contained rooms in cheap seaside towns like Eastbourne and Hastings — costly for taxpayers and grim for the people affected, especially those with jobs in Tunbridge Wells.

So the council recently spent £2m to buy back a building called Dowding House. The idea was to use the 25 flats in the building to house homeless people. Within two weeks of opening, it was full.

One might argue that, if people cannot afford market rents in a place like Tunbridge Wells, they should move somewhere cheaper. The housing market is far from uniformly overheated: there are plenty of places, such as seaside towns like Blackpool in the north-west, with a surplus of cheap housing. But, as Blackpool can testify, concentrating England’s poorest people in its poorest places can exacerbate decline.

Nor would a place like Tunbridge Wells function if all the low-paid workers emptied out. “Who do you think supplies your coffee in the morning, cleans your train, repairs your shoes, mows your grass?” asks Mr Hepworth. “Do we want to shift young people into Blackpool where they’re not going to work and they’re going to be spending your taxes from now until kingdom come?”

This is where Habitat’s project with the Quakers comes in. The charity’s model in the US is to build houses from scratch with the help of the community. But land prices in England are simply too expensive to make that viable. Instead, it has to be inventive. The Tunbridge Wells project began because the Quakers needed to downsize, but wanted to do something useful with the rest of their building. Habitat invested £500,000 in the conversion, the Quakers raised £100,000 and the council contributed £250,000.

It solves a problem for the YMCA and the council. At the moment when people are ready to move on from the hostel’s intensive support, it is hard to find somewhere they can afford to live. That causes a blockage. The new shared flats, which will cost tenants £77 a week each, will be affordable on a low income, or on housing benefit if anyone loses their job. Ms Lewis lights up when she talks about it. “I’m so glad we had the funds to assist them [Habitat for Humanity] in that project, because it’s unique.”

For Mr Russell and Mr Chantler, the renovated Quakers house is not just a place to live, it is a chance to leave homelessness behind. Mr Russell says he left home when he was 16 after his stepfather punched him in the jaw. His grandmother took him in but she was living in special accommodation for older people, so he could not stay with her forever. Though he has not slept rough, he always gives change to people sleeping in Tunbridge Wells’ doorways. “I don’t know how it is, but I know how it is to feel it,” he says. “Why would you look at someone who hasn’t got anything as if they’re nothing?”

Mr Chantler was homeless and sofa-surfing between friends and relatives before he was given a place at the YMCA, often not knowing where he would sleep from one night to the next. He was always “treading on eggshells”, worrying he was putting pressure on people he stayed with. “It starts destroying all the relationships you have with anyone, because they kind of don’t see you the same.”

In fact, he says, he has felt homeless ever since he was a child, being passed between his mum and dad. One of his earliest memories is his father punching his fist through the wall the night his parents split up.

“I think, if you don’t feel like you belong anywhere, you haven’t got a home,” he says. “It’s the difference between a house and a home.” After feeling insecure and on edge for most of his life, this is why his new, warm, safe room, with its views over the rooftops, means the start of something new. “If you’re comfortable being somewhere, you can call it a home.”

Photographs by Charlie Bibby

• Your gift will be doubled

If you donate to Habitat for Humanity through the FT’s Seasonal Appeal, the Hilti Foundation, a charitable organisation, has generously agreed to match your gift. Click here to donate now.

Read more about our Seasonal Appeal partner Habitat for Humanity: ft.com/habitat-facts

Comments