How UK companies got a head start on cutting carbon emissions

Simply sign up to the UK companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

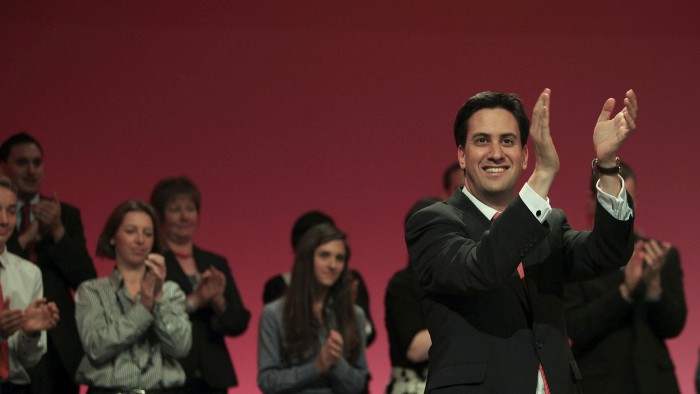

It is almost 13 years since Ed Miliband, the then youthful UK energy secretary, dramatically tightened Britain’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the flagship Climate Change Act.

This legislation, effective from November 2008, tied the UK to a set of environmental commitments that were virtually unprecedented for a large industrialised nation.

Miliband went on to lead Britain’s opposition Labour party for five years, only to lose the next general election. But the Climate Change Act is a powerful legacy.

Its ambition arguably made it easier for subsequent governments to impose further tough climate targets. It is also one of the main reasons why over 90 of the 300 names in the FT’s listing of Europe’s Climate Leaders are British.

At the last minute, Miliband increased the British pledge on net GHG emissions, with a commitment to cut them by 80 per cent from 1990 levels by 2050, instead of the previous target of 60 per cent. Successive governments would have to abide by a series of rolling medium-term targets called “carbon budgets”, which would place caps on economy-wide emissions and be monitored independently.

“The costs of not acting are worse than the costs of acting,” Miliband declared at the time. “So I don’t think there is an option not to act.”

Keen to be green

It helped that a lot of UK businesses appeared to agree, and continue to do so. Nick Molho, executive director of the Aldersgate Group — a green alliance of business and civic leaders — says there is a long history of British companies showing “strong environmental and social governance ethics” in their behaviour.

Many of them voluntarily signed up to the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures scheme, set up by the Financial Stability Board in 2015. This market-driven initiative, championed by Mark Carney, then Bank of England governor and FSB chair, aims to standardise the way companies report climate risk.

According to the TCFD’s 2020 status report, the UK is now the European country with the greatest number of companies supporting the initiative, and is tied with the US for second place globally, behind Japan.

More stories from this report

Can businesses deliver on their climate promises?

Companies grapple with Scope 3 emissions challenge

Consumers keen to be green but confused by companies’ claims

Banks feel the heat on financed emissions

We know net zero is the destination — now let’s get moving

Fashion fails to factor in supply chain carbon

UK companies also backed plans in 2019, by the then prime minister Theresa May, to set a “net zero 2050 target” for emissions. More than 130 businesses and trade organisations encouraged May to go ahead with the policy.

Molho admits there is an element of self-interest, with businesses quick to realise the threat that climate change poses to their profits. “There’s a real awareness of how their supply chains are interconnected, the fact that unmitigated climate change has already disrupted a lot of their business operations,” he says.

The UK’s food industry, for example, was hit by exceptionally warm summers in 2018 and 2019. Many retailers were “pushed to the limit” in finding alternative suppliers of commodities, Molho says.

Comply or else

But while many businesses have signed up to the climate agenda voluntarily, successive governments have also made it harder for others not to take action. Not only did the UK agree to an 80 per cent and then a 100 per cent net zero GHG emissions target long before many other countries, it also set a tougher midterm target for 2030 than the EU: 68 per cent against 55 per cent.

On other fronts, there has been a rapid shift to compulsion — for example, a 2024 ban on coal-fired power stations. At the same time, the UK’s energy subsidy regime has been heavily weighted towards low-carbon electricity. That alone has been a significant factor in the cutting of emissions by all large companies, says James Diggle, head of energy and climate change at employers’ organisation the CBI. “UK business has — by default — cut its CO2 emissions because they are all using greener electricity,” he says.

There has been an accelerating trend towards enforced disclosure of climate impact, too. In 2013, the coalition government led by David Cameron forced all listed companies to report on their global GHG emissions. Then, last November, Rishi Sunak, the chancellor, announced measures to force large listed companies to report their climate risk exposure using the TCFD framework by 2025 — including banks, insurance companies and pension schemes.

Some of the biggest businesses, dubbed “premium listed companies”, will have to make these disclosures from this year. That may take a lot of work: despite UK plc’s support for the scheme, a recent study by advisory firm FTI Consulting and research company Sentieo found that full compliance was patchy.

Pressure is also coming from the BoE, which in June will launch a climate stress test for financial institutions, under which banks and insurers will have to consider whether their capital reserves are commensurate with climate risks.

Even so, climate campaigners believe there is much more to be done to ensure the country can hit its targets.

Although the government has introduced ambitious new policies including a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030, and a target of 40GW of offshore windpower by 2030, other necessary steps, such as reducing emissions from home heating, have not yet been addressed.

Diggle says the easiest changes have been made, with greater challenges to come, particularly in construction and heavy industry. “Specific sectors will need more help from the government,” he says.

Comments