Understanding what makes inventors tick

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

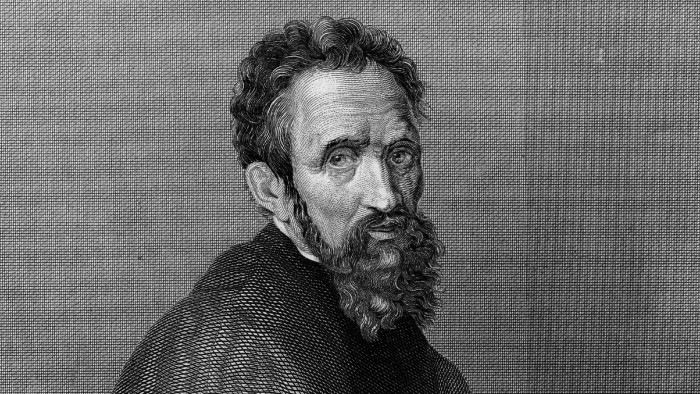

Highly creative people both intrigue and irritate us. We admire the minds of people such as Steve Jobs and Michaelangelo, marvel at their achievements, but may weary of their personalities, which can be egotistical and moody.

Technology and industry are increasingly reliant on innovation and are eager to support creative individuals. This can be frustrating, however, when the process of innovation goes against the grain of businesses that demand productivity and efficiency, and have little tolerance for errors. Creative people can be enthused about a project, only to lose interest as their attention shifts elsewhere. They need time to mull over ideas, which makes them appear to be doing very little. In their own time zone, they are often late or forget meetings, to the annoyance of managers.

Understanding their unique ways of thinking is essential to getting the best out of them. Two qualities that define creativity are divergent thinking — thinking beyond normal boundaries — and cognitive flexibility, which is the capacity to restructure ideas and see connections that others miss.

People with these qualities risk going beyond what is safe and familiar, which most of us would avoid for fear of being wrong or damaging our reputations. While most of us look for the “correct” or conventional answers, they seek novel solutions and new associations.

Many of these ideas will never come to fruition, so creative thinkers need to become hardened to disappointment and failure. Steve Jobs was famously fired and then rehired at Apple. Henry Ford filed for bankruptcy twice before finding success with the Ford Motor Company. However, their resilience and confidence in their ideas can make innovators appear arrogant and egotistical to their colleagues.

Science has found links between highly creative, healthy people and individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar illness, with some brain chemistry features in common. Connections have also been made between creative individuals and relatives with a mental illness, suggesting a genetic link.

Dr Shelley Carson, a lecturer in psychology at Harvard University and author of Your Creative Brain, says creativity and schizotypal personality features often go hand in hand because one of the underlying features for both is a propensity for cognitive disinhibition.

This means a person is less able to block out extraneous information. “They lack [cognitive] filters which the rest of us have for social appropriateness, or they have more porous cognitive filters,” Dr Carson says. “So, information that most people might ordinarily suppress makes it through into conscious awareness for these people. This provides more pieces of information which can be combined, and then recombined, in more original ways to form creative ideas.” She compares the insights of highly creative people to how psychotic thoughts emerge in the minds of mentally ill people.

“Cognitive disinhibition is also likely at the heart of what we think of as the ‘aha!’ experience. During moments of insight, cognitive filters relax momentarily and allow ideas that are on the brain’s back burners to leap forward into conscious awareness,” she says. Her ideas are supported by research at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, which has shown that the dopamine system in the brains of healthy, highly creative people is similar to that found in people with schizophrenia.

Dopamine receptor genes are linked to divergent thinking, inherent in creativity and also associated with psychotic thoughts. Both groups have fewer of the “D2” type dopamine receptors in the thalamus, the brain’s filtering system. This enables a high flow of information from the thalamus to the frontal lobes, which are responsible for deciphering information and where thoughts become constructive and meaningful.

Ms Carson says novel ideas result from a combination of high IQ, a capacity to hold many ideas in mind, and cognitive flexibility. “When you can combine those with the ability to [cognitively] disinhibit then very often highly creative ideas result.”

Gary Klein, a cognitive psychologist and author of Seeing What Others Don’t, believes many companies have much to learn in facilitating creativity. Their first reactions to innovations are often nervousness and distrust because insights can be disruptive and can lead to errors.

If businesses are to encourage innovation they need to learn to tolerate a degree of anxiety and uncertainty. Mr Klein says managers need to ask: “What are we doing that’s getting in the way of innovation?” For example, strictly adhering to a plan risks restricting the creative process, as can an emphasis on data gathering and voting by consensus.

“All you need is one or two people who become nervous about a creative idea and the team backs off and moves in a safer direction,” he says. “Organisations can look to see if they are evaluating new proposals so heavily in terms of weaknesses that they kill ideas.” He adds: “If you want to kill a creative idea, have an organisation that’s very hierarchical, which means it has to be approved by everybody up the chain. It only takes one person in the chain to kill an idea.”

Comments