Krishna Reddy — no ordinary printmaker

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For most of 2020 I remained equanimous about the lack of art seen in real life. But when Experimenter Gallery sent me a file of images depicting the prints of Krishna Reddy, my equilibrium deserted me. Only fear of arrest prevented me from jumping on a plane to Kolkata to see the real thing.

It’s a measure of Reddy’s achievement that he triggered this longing for three-dimensional experience with prints — a medium often regarded as essentially one-dimensional.

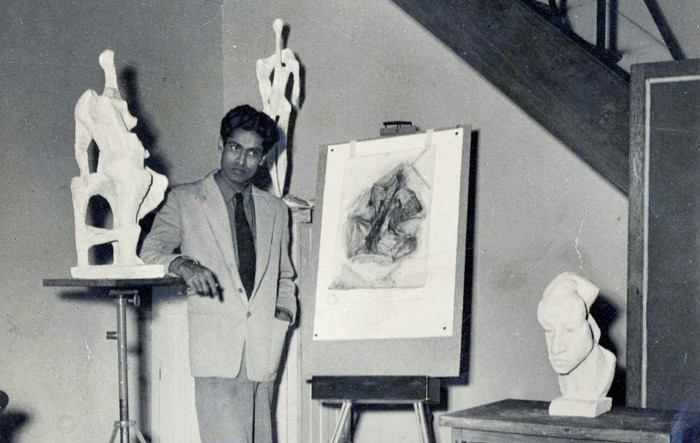

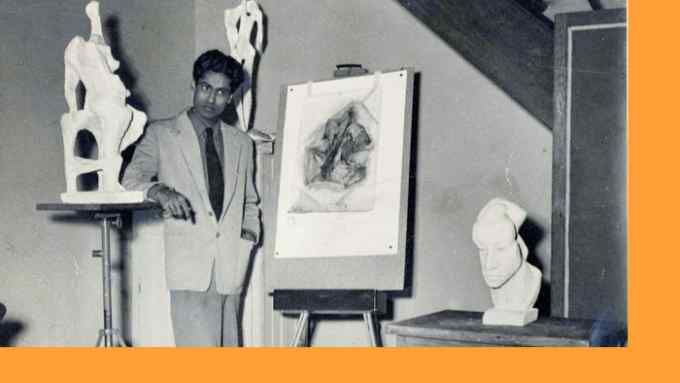

Reddy was no ordinary printmaker. His development of a new printing technique inspired generations of artists. Born into a family of farm workers in the south-eastern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh in 1925, he studied first in India before heading to Europe. After a spell at the Slade in London, he moved to Paris and joined Atelier 17, a printmaking workshop founded by Stanley William Hayter, a British Surrealist artist.

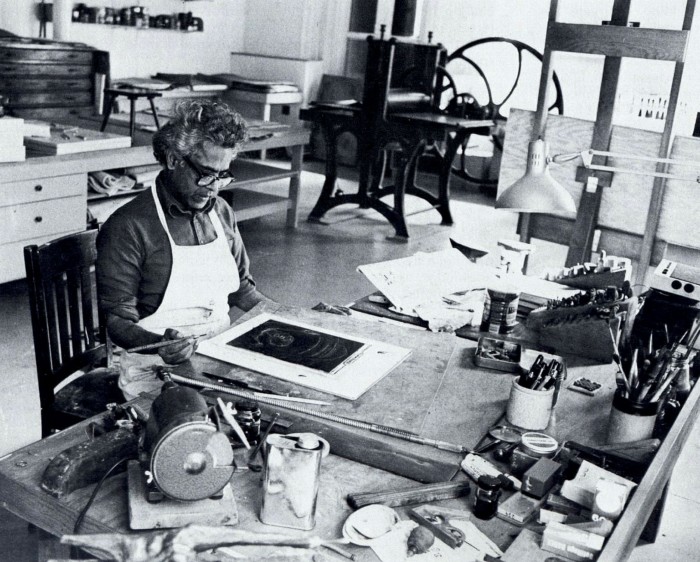

Reddy, who also developed a fine career as a sculptor, would later become director of Atelier 17. While there, he worked alongside Hayter to develop the new technique of “viscosity printing”, which involved applying multiple colours to the same metal plate. Its success depends on the artist’s skill at blending the inks with oil to create varied levels of viscosity so that they are absorbed to different depths on the incised plate. Facilitated by rollers of variable softness, the process means that the colours maintain their autonomy yet possess an organic relationship with each other that is often lacking in conventional colour printing.

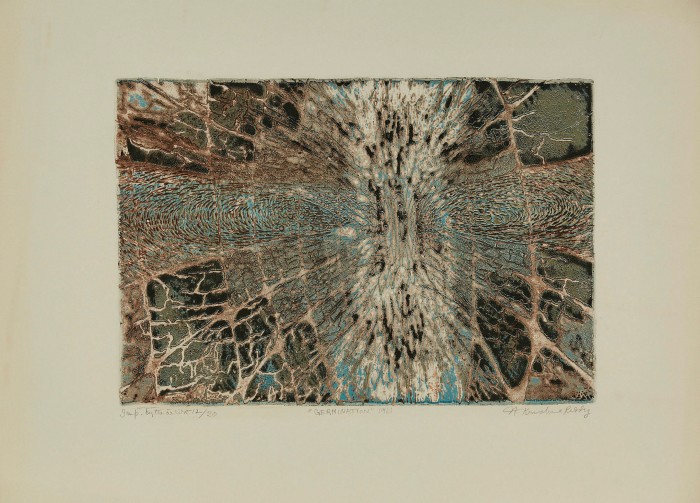

The results are images of extraordinary chromatic and textural complexity. Made between 1958 and 1972, the eight prints on show with Kolkata’s Experimenter gallery at this week’s Art Basel online viewing rooms include Germination (1961). Expanding outwards from a small dark kernel, a pattern of lines and patches ripple through turquoise, black, brown, grey, faun and bone-white to evoke an organism as natural as the whorls on a tree trunk or the hide of a big cat. At once map and landscape, process and material, even on a digital screen the print’s ridges and furrows are tantalisingly tactile.

The intense vitality of Germination originates in Reddy’s profound rapport with the natural world. Aside from his own rural origins, he studied botany and biology at Visva Bharati University in Santiniketan in West Bengal. Founded by the legendary poet Rabindranath Tagore as an alternative to more rigid colonial education systems, the school was renowned for its experimental pedagogy, much of which took place in nature. Prior to his arrival there, Reddy had also studied at the Rishi Valley School under the spiritual teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti.

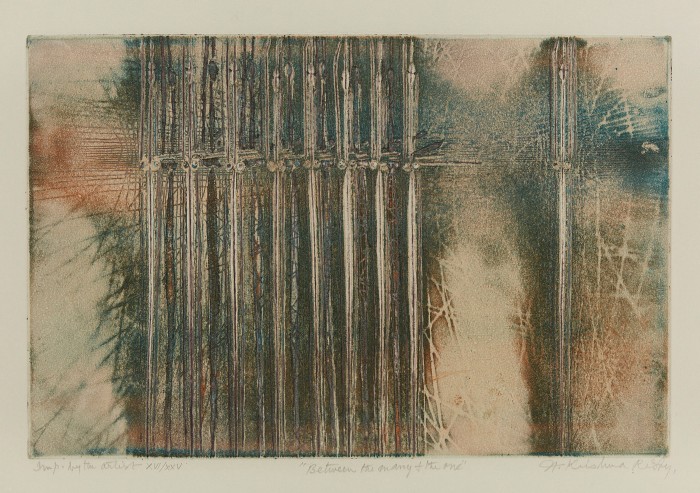

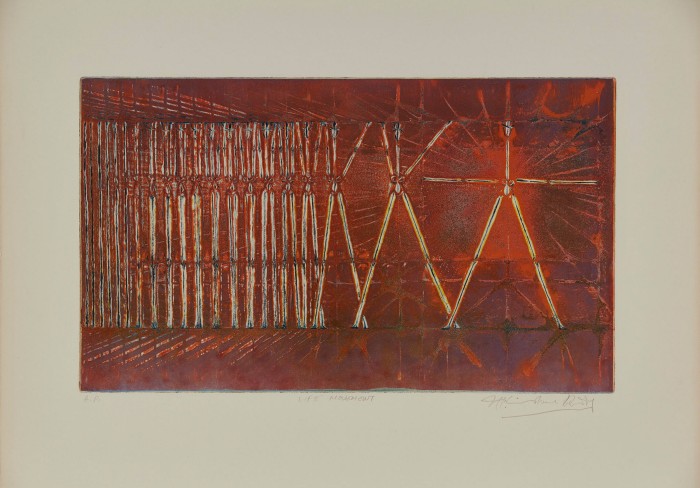

Drawing on Krishnamurti’s teaching, Reddy approached humanity and nature as inextricable, interdependent elements of a single organism. Entitled “Between the Many & the One”, a print from 1971 eloquently illustrates Reddy’s feeling for this collective bond. It shows a thicket of narrow verticals laid over a matrix of thatched lines separated from another single perpendicular form by an amorphous teal-green space whose mottled surface quivers with fertile energy from the tension between the forms.

In the Basel prints, Reddy is an artist seeking to express the primordial harmony of our world. Yet that spiritual impulse coexisted with a political counterpart rooted in his own experience. To support the anti-colonial movement Quit India, he turned his hand to making posters and employed the same skills to support the Algerian revolution while in Paris. Undoubtedly among his most acclaimed projects is the sequence of prints and bronze sculptures entitled “Demonstrators”, which emerged after he witnessed the incendiary protests in Paris in 1968. Showing a row of stark, anonymous figures bunched together yet perceptibly separate, the works capture both the solidarity essential to political resistance and the personal loneliness that so often accompanies it.

Over half a century later, “Demonstrators” retains its power. Jennifer Farrell, associate curator of drawings and prints at the Metropolitan Museum, recalls how the print acted as a magnet after the first Women’s March in New York City in January 2017. “There were all these women in pink hats coming in and taking photos!” says Farrell, when we catch up on Zoom. “Clearly [‘Demonstrators’] spoke to people and they made a beeline for it.”

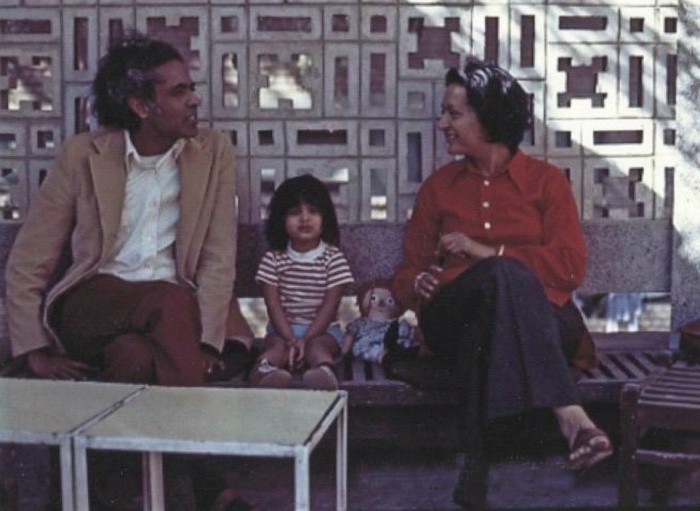

Three years after his death, Reddy’s legacy is immense. For 40 years he taught at New York University where he was the only professor of colour in the department. “He was a really good teacher,” recalls Reddy’s wife, the artist Judith Blum Reddy. “He always told his students to concentrate less on technique, a common trap for printmakers, and more on expression.”

He had a particularly intimate bond with fellow printmaker Zarina Hashmi (known as Zarina). She was born in Aligarh, in India, in 1937, and her life and work were inextricable from the trauma of partition in 1947. In the years prior to her death last year, she was finally receiving the recognition she deserved for a practice, based around Japanese woodblock printing, that maps a spare, poetic odyssey through her experiences of homeland, dislocation, family and loss.

Zarina, who was based in Paris for several years, studied viscosity printing at Atelier 17. Although her work took its own direction, she forged a life-long friendship with the Reddys. In 2016, Farrell and Navina Najat Haidar, curator in charge of the Metropolitan Museum’s Islamic Art Department, mounted an exhibition of work by Zarina, Krishna Reddy and Hayter. During a symposium, in which Reddy was also present, Zarina described him as her “teacher”, then went on to say: “If I had never looked at Krishna’s work, I would never have known what printmaking is all about.”

Haidar meanwhile describes Zarina and Reddy as “opposite mirrors” who “moved together through time and . . . on a more profound and philosophical level”.

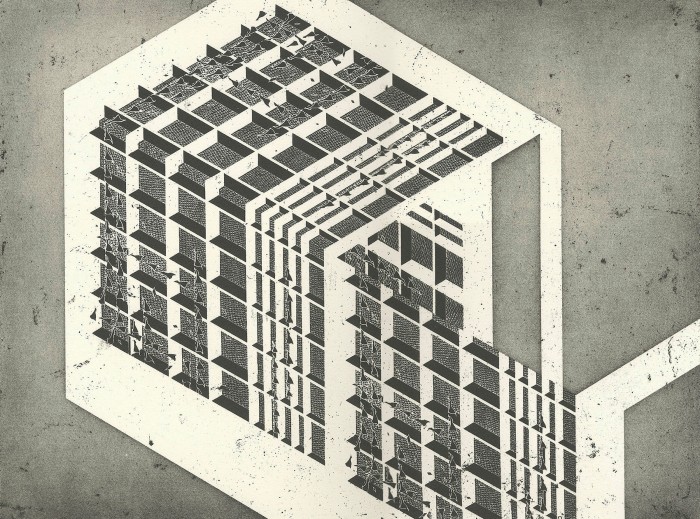

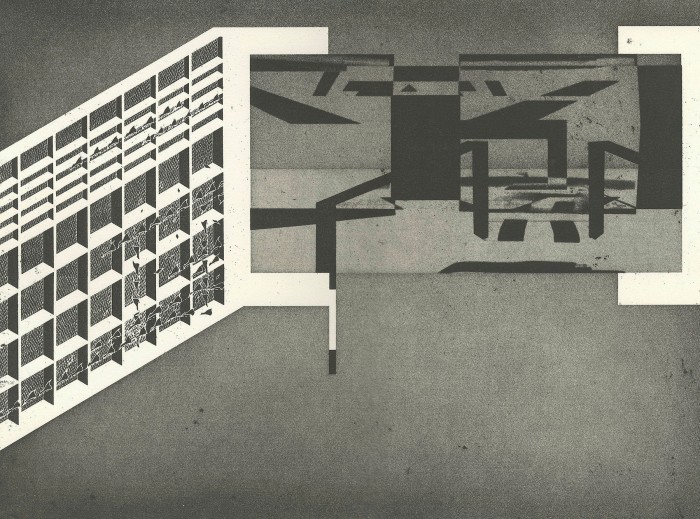

Reddy’s sense of expressive possibility also inspired a younger generation, including contemporary artist Seher Shah. Spanning printmaking, drawing and sculpture, Shah’s subtle, measured practice explores space as a conduit for human experience, memory and imagination. An artist whose materials include graphite dust, architectural drawing tools, photography and musical scores, Shah says that Reddy’s skill at “conjuring worlds, collapsing scales and working with materiality” struck her from the moment she saw them. “As someone who has been greatly influenced by intaglio printmaking and its process,” she continues, “his prints continue to resonate with me through the power of his materiality and the vast fields of space and connectivity that he constructed and left behind.”

His pioneering efforts are all the more impressive given that printmaking has historically occupied a lowly place on the artistic hierarchy. “The prejudice against printmaking is very real,” confirms Farrell, adding that Reddy was working at a time when even painting was considered a dead practice. “Printmaking wasn’t even discussed!”

Today, as rigid boundaries crumble in art and beyond, printmaking commands the respect this historic practice deserves. Furthermore, as Haidar points out, the rich creative exchanges between Reddy and his followers are rooted in printmaking’s heritage. “In Mughal era [prints] sometimes you can see in the inscriptions who did the composition, who did the portraits and who did the colour,” she observes, as she points out that print workshops have always been somewhere “artists have been asking ‘how do you collaborate’? ‘How do you influence each other?’”

Thanks in part to Reddy’s bold, generous talent, that conversation is still enormously fertile.

OVR: Pioneers, March 24-27, artbasel.com

experimenter.in

Comments