Air pollution: why London struggles to breathe

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

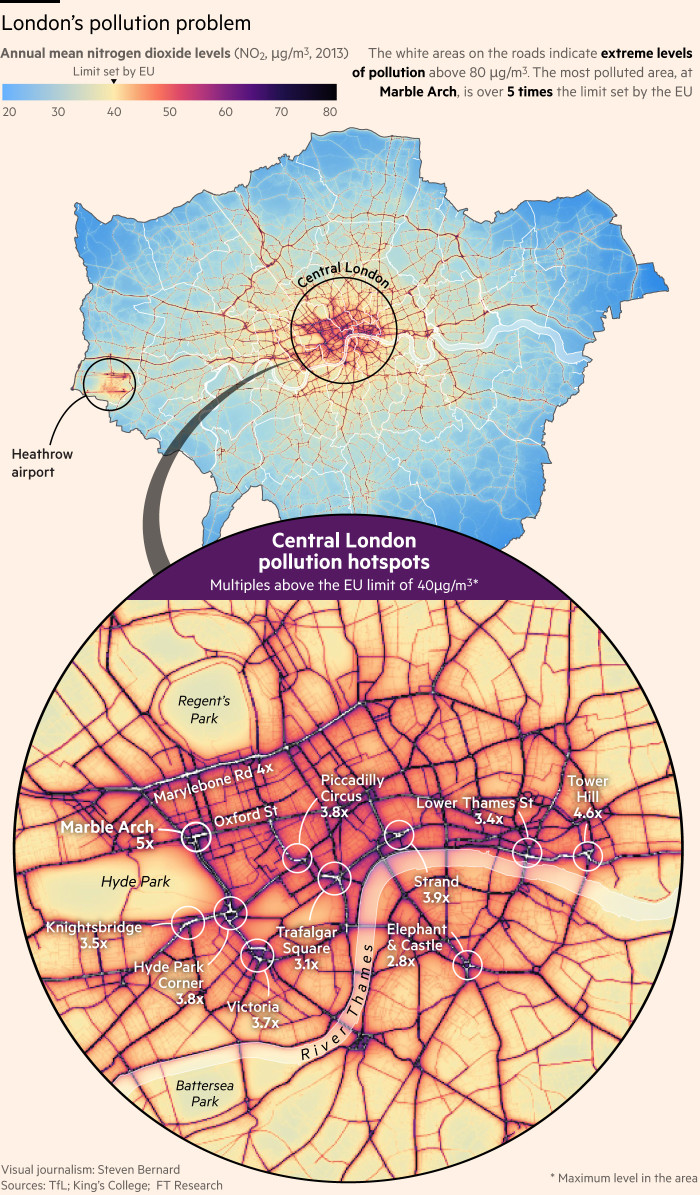

Four years ago Sophie Power was walking along Marylebone Road, thinking of the son she was pregnant with at the time. The buses, lorries and cabs clogging the central London thoroughfare make it one of the most polluted places in the UK.

“I wondered how to protect him,” she says, pointing to a study that found children in polluted areas develop stunted lung capacity that is 8 to 10 per cent smaller as a result. “The pollution inevitably has an impact,” she says.

Although London’s air often appears clear to the naked eye, the city has suffered from illegal levels of air pollution since 2010, with particularly dangerous levels of nitrogen dioxide, which comes mainly from diesel vehicles. This summer’s unusually hot and sunny weather has caused surges in ozone — produced when sunlight reacts with nitrogen dioxide — that have prompted multiple pollution warnings.

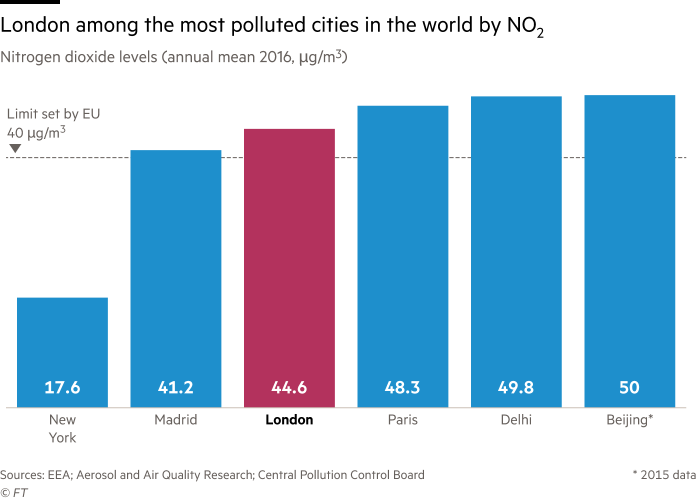

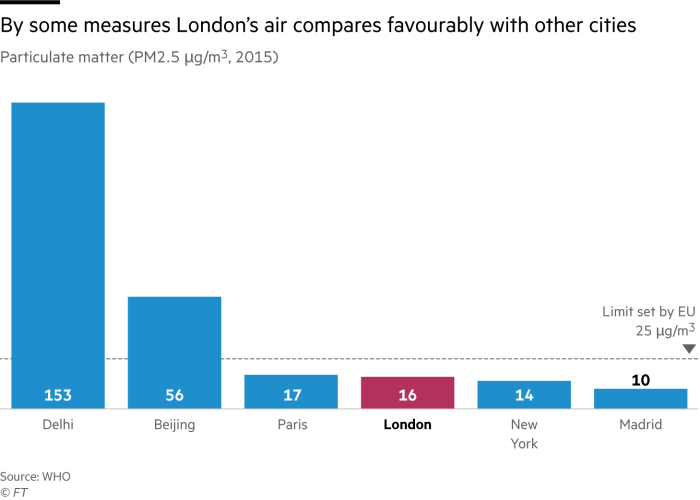

While cities such as Beijing or New Delhi usually attract more headlines, the stubborn air pollution in London shows just how intractable the problem can be. Under some measures, such as extremely small air particles, the smog in New Delhi and Beijing is much worse than London. But in terms of nitrogen dioxide, which inflames lungs and is linked to shorter life expectancy, London is nearly as bad as the Chinese and Indian capitals — and much worse than other developed cities such as New York or Madrid.

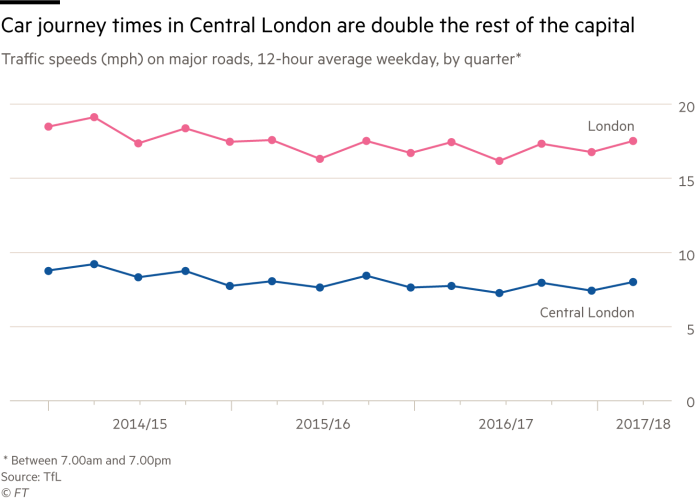

This is despite dramatic shifts in transport policy with increased cycling and a congestion charge helping to reduce the number of vehicles on the roads in central London by 25 per cent in the past decade. Yet despite its pioneering schemes, road works, cycle lanes and the rise of private hire vehicles has slowed traffic to a crawl.

“These are the trenches,” says Simon Birkett, a banker-turned-air-campaigner who founded Clean Air London, a non-profit organisation. “If you cannot tackle this problem, which is much more tangible for people, you can forget about other problems,” he says, pointing out that climate change is much more complex.

With the growing amount of research and political attention focused on air pollution, experts sometimes draw analogies to the way the Great Smog of 1952 radically changed how the city thought about its air. “We are in a similar moment now,” says one local official. “It’s not as visible, but because the particles are so small, the actual health effects can be more significant.”

Shirley Rodrigues, London’s deputy mayor, says the city has reached a “tipping point” in terms of taking action. “It’s not only [because of] the thousands of deaths brought on early, but also the pernicious, chronic illnesses that are costing the health service a lot of money,” she says. “It is affecting quality of life.”

This urgency has been compounded by a series of lawsuits in which judges ruled the government was not doing enough to comply with the EU’s legally binding air pollution limits.

Part of the reason for the shift is that a lot more is now known about how air pollution impacts human health: In London air pollution contributes to more than 9,000 premature deaths each year, according to a study by King’s College. This month researchers at Queen Mary University of London found that even very small amounts of pollution were linked to changes in heart structure.

Ms Power’s concern about her own exposure to air pollution led her to launch an air filtration company, Airlabs, which has created pilot clean air zones at bus stops and in schools. Her second child, just three months old, has a personal air filter inside his pram.

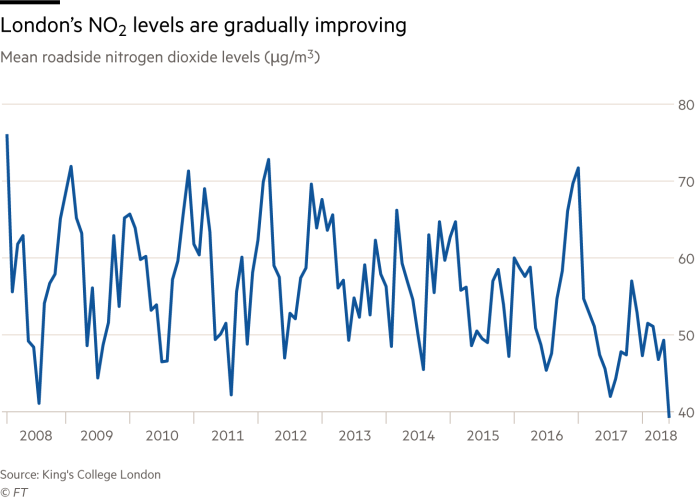

While London’s air monitoring stations show that pollution has been slowly improving in recent years by most measures, Ms Power points out that individual exposure can be much worse than the monitors suggest. “Overall, the picture in London is not getting materially better.”

Sadiq Khan, who became mayor in 2016, has made fighting air pollution a key priority, with a new ultra-low emission zone for central London and a commitment to spend £800m on air quality initiatives over five years.

Government modelling suggests that London air will not comply with legal limits until 2025.

To understand how London’s air got so bad in the first place, look no further than Upper Thames Street, which stretches from London Bridge toward Blackfriars, near the riverbank. As fitness-minded runners jog by, a stream of slow-moving traffic, mostly lorries and vans delivering to the city, stops and starts ahead of a set of traffic lights.

At an office building on the corner of Thames Street and Cousin Lane, the vials and tubes of the monitoring station protrude from an entrance. The data they gather show the highest pollution in all of London, with nitrogen dioxide levels exceeding critical levels more than 120 times last year. (The legal limit is 18 times a year.) The City of London, the traditional financial district which is distinct from the Greater London Authority that covers the entire metropolis, is home to two of the five worst hotspots on this measure.

City officials blame the Square Mile’s combination of medieval street design, high buildings, and persistent pollution from vehicle emissions. As in the rest of London, the congested traffic and diesel vehicles are two key culprits. “A lot of the pollution that we breathe on the streets around us, and the hotspots, are caused by diesel vehicles in London,” says Gary Fuller, the King’s College scientist who developed the London Air Quality Network of monitoring stations.

When London missed the binding air quality EU limits that came into force in 2010, it was largely due to diesel vehicles, Mr Fuller says, because they emitted higher levels of nitrogen dioxide in the real world than in lab tests.

The legacy of diesel, initially billed as a cleaner fuel because it produces less carbon dioxide, has plagued other European capitals such as Madrid and Paris.

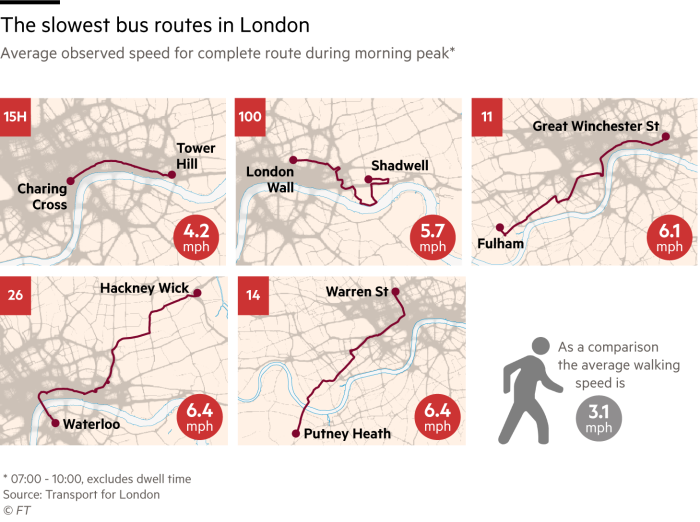

In London, congestion has compounded the effect of the diesel fumes. Traffic speeds in central London average eight miles per hour on weekdays — a figure that has decreased in recent years. Although the total number of vehicles entering central London has fallen by about 30 per cent since the congestion charge was introduced, the number of private hire vehicles entering central London — where they are exempt from the charge — has more than quadrupled over the same period.

“The medieval road system, if you look at the layout and the size of the roads, they were originally designed for horse and cart,” says Ruth Calderwood, City of London air quality manager.

Road works, private hire vehicles and online delivery vans have all contributed to the congestion problem, according to Transport for London, which is considering whether to extend the congestion charge to private hire vehicles. The stop-and-go nature of congested traffic exacerbates vehicle emissions, which are often highest when a vehicle is accelerating.

Political inaction has also played a part. But in the years since then, air pollution has not always been a high priority. When Boris Johnson was mayor, between 2008 and 2016, he scrapped an extension of the congestion zone, and delayed plans for a low-emission zone.

Mr Khan, himself an asthma sufferer, has put pollution higher on the agenda. The congestion charge has been augmented by a T-charge on the most polluting vehicles (“T” stands for toxicity). That will be replaced next year by an “ultra-low emission zone” charging older vehicles. Since the beginning of the year, all new single-decker buses are zero-emission, and new taxis must be hybrid or electric.

But even as the new ultra-low emission zone penalises polluting vehicles, some environmental advocates say a more nuanced road system is needed, one that charges cars according to how much they drive, where they drive, and how much they emit.

“We are sitting on a bit of a health time bomb here,” says Caroline Russell, a member of the London Assembly for Britain’s Green party. “We really need to be making sure people see how much better our lives could be if we had a less car-dependent transport system.”

Brexit could present a further challenge for London’s fight to clear its air, because EU laws have until now provided the strictest air quality standards that the UK is obliged to meet. Last month, a clean air bill was introduced in the House of Lords that would make clean air a human right, and mandate that air quality be taken into consideration with all new government policies.

“The concern post-Brexit is that if that falls away, there is a real risk that ambition will fall away even further on this issue,” says Katie Nield, a lawyer with ClientEarth, a non-profit group.

In May, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs released a draft clean air strategy that described air quality as the “largest environmental health risk” in the UK.

But as the experience of London shows, air pollution has proved exceptionally stubborn. Even if vehicle emissions are curbed, issues such as aircraft and agricultural pollution could prove more challenging yet. And as more research shows how damaging pollution can be to human health, the World Health Organization is set to tighten its guidance for the level of exposure considered safe. The fight to clear London’s air may get harder.

Letter in response to this article:

London’s dirty air can’t be compared to New Delhi’s / From Murad Qureshi, London, UK

Do you experience air pollution in your daily life? What solutions to this problem do you think are most promising? Share your thoughts and ideas in the comments below. Leslie Hook will be responding intermittently through the day.

Comments