Can the world feed itself sustainably? A primer in seven charts

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

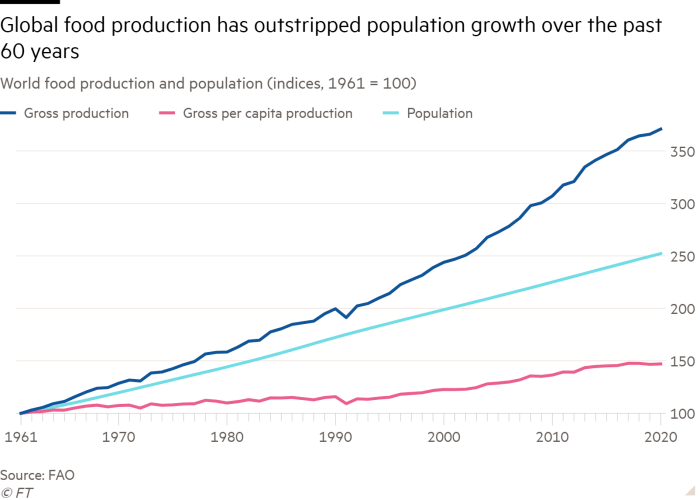

Agriculture is not what it was — and, given that the global population is also not what it was, that may seem a good thing. Since the middle of the last century, new crop varieties, new cultivation techniques and new technologies have brought about a revolution in productivity: the average hectare, for example, now yields three times the tonnage of cereals that it did in 1961, according to Our World in Data.

But whether this is sustainable is a different matter. The costs that the modern food system imposes — in terms of deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity and human health — are becoming clearer year by hotter year. Brazil provides a case in point: an agricultural powerhouse, it may also be nearing a catastrophic ecological tipping point beyond which its rainforest cannot regenerate.

The question, then, is whether the world’s farmers and food businesses can feed more people in a healthy and equitable way without adding to the environmental degradation and global warming that threaten to make some populated areas unlivable.

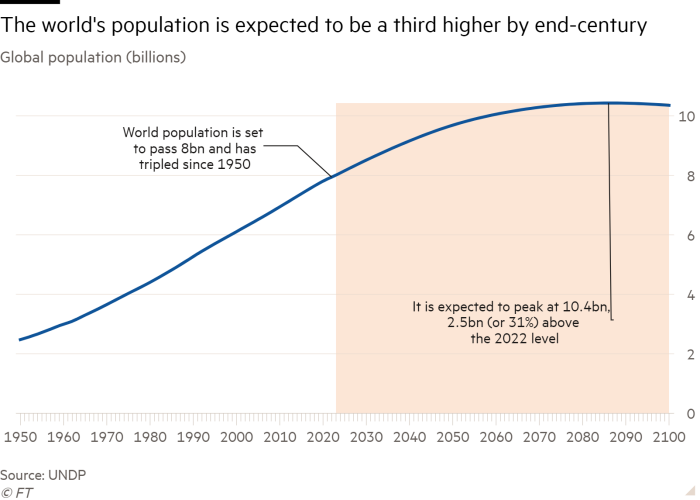

The following charts offer an overview of some of the key factors to consider — food for thought, if you like — starting with the sheer number of mouths to feed.

The rate of growth of the world’s population is slowing, but the 9bn mark is imminent. The peak, 60 years or so from now, is expected to be 10.4bn people.

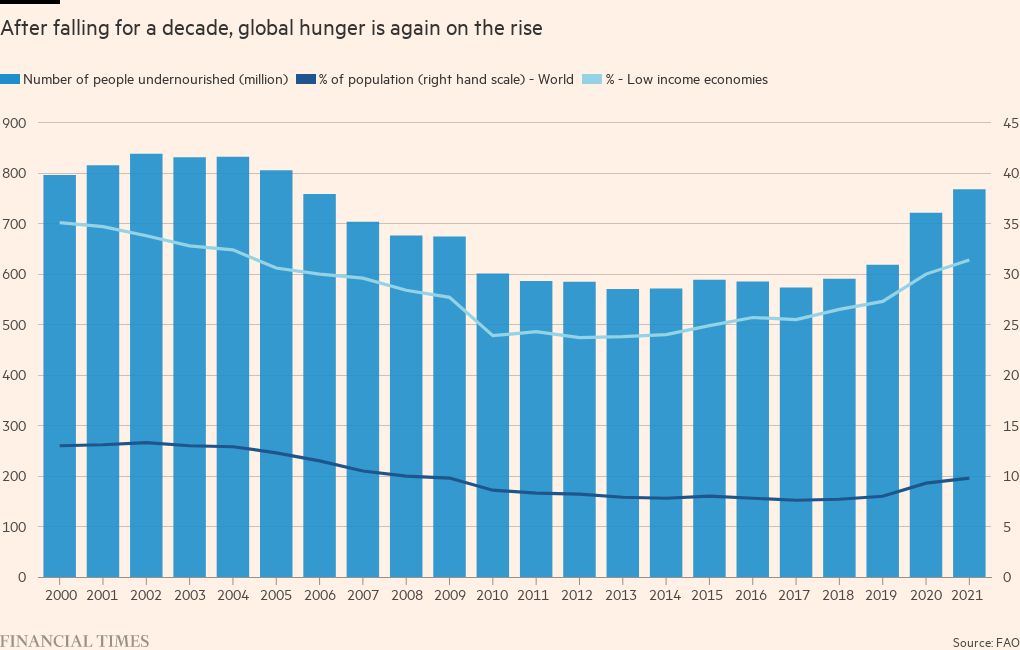

Meanwhile, the trend in the reduction of hunger globally is reversing — as starkly described in the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s 2022 report on food security and nutrition. “This year’s report,” the FAO says, “should dispel any lingering doubts that the world is moving backwards in its efforts to end hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition.”

This has prompted widespread concern about how an extra 2.5bn people are to be fed, particularly as rising real incomes in the developing world are usually associated with increased consumption of resource-intensive meat.

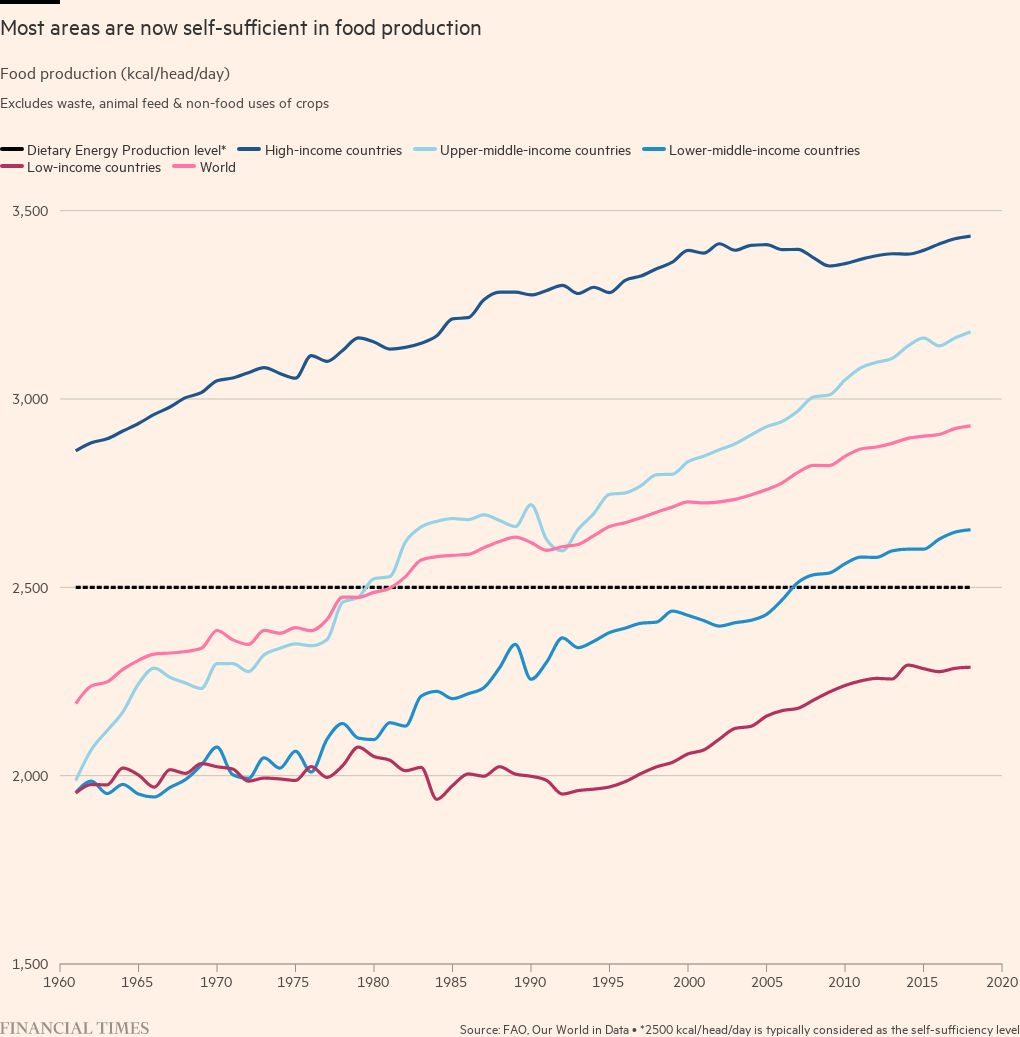

Yet agricultural production has consistently outpaced population growth . . .

. . . and all but the poorest countries are now self-sufficient in food, according to the FAO’s definition, producing enough calories to meet basic dietary requirements.

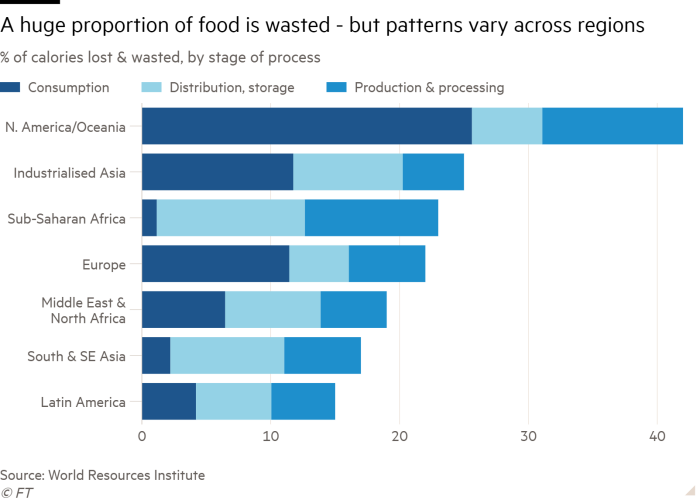

It does not follow, however, that current methods of production are environmentally sustainable. Discussion of how to make them so is dominated by two main issues: reducing food waste and dietary change.

A huge amount of food is wasted — and so, in effect, are the land, water and other resources that went into producing it. In advanced countries, food is wasted predominantly by households while, in developing economies, most waste occurs due to inefficient production and distribution.

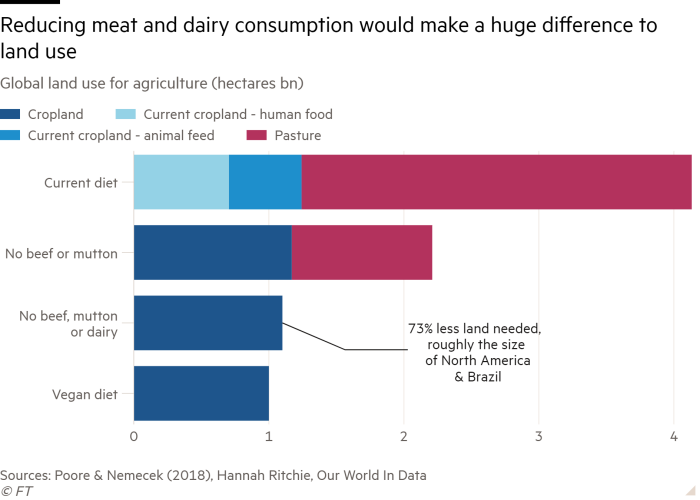

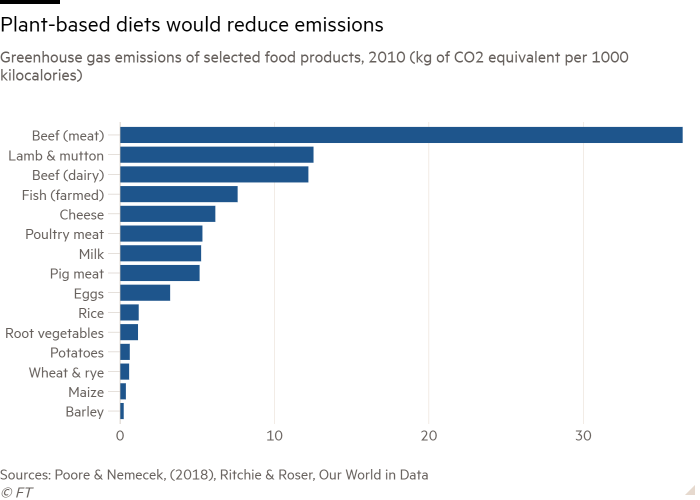

Dietary change, too, would reduce pressure on the world’s ecosystems. If beef and mutton alone were eliminated from the world’s diet, agricultural land use would halve. Cut out dairy products, as well, and it would halve again.

In addition, moving to plant-based diets would help reduce the food industry’s huge contribution to greenhouse gas emissions — currently, it accounts for just under a third of the total.

Eating habits are hard to change, though. No matter how eloquent a chart may be, it does not follow that hungry consumers — and the businesses that serve them — will be easily swayed. A sustainable diet for the planet is likely to be a work in progress for a long time to come.

Comments