Will international investors like Lula more than Bolsonaro?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s victory in Brazil’s presidential election will unlock a flood of money from international investors who shunned the country under President Jair Bolsonaro because of his terrible environmental record.

This thesis was common currency this year among political analysts in Brazil and commentators overseas. Lula himself hinted at it, accusing Bolsonaro of leaving the country “more isolated than Cuba” and adding: “Nobody wants to come here anymore.”

There is just one problem: the facts tell a different story. Amazon deforestation did surge under Bolsonaro to a 13-year high and many European and Latin American countries shunned the hard-right president diplomatically.

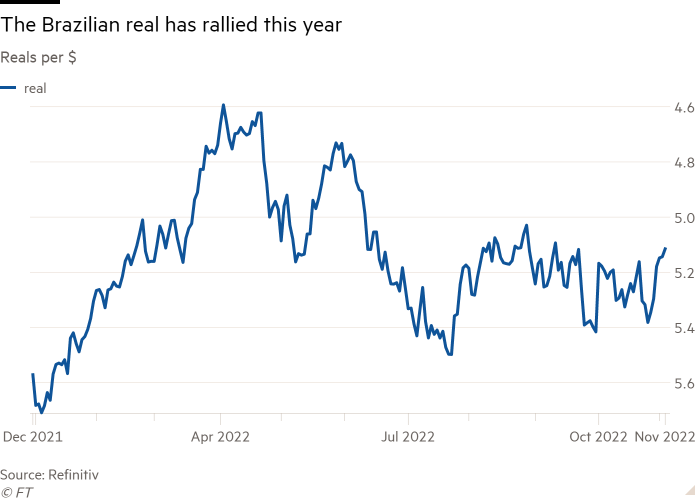

But most investors never left Brazil over environmental, social and corporate governance concerns and many were drawn in during Bolsonaro’s tenure by strong economic fundamentals, high real interest rates and the pro-market stance of the Friedmanite finance minister, Paulo Guedes.

“The preferred strategy of most investors [under Bolsonaro] has been one of constructive engagement rather than disinvestment,” says Graham Stock, partner at BlueBay Asset Management, who co-chaired an investor dialogue on deforestation with the Bolsonaro government. “As a result there isn’t this wall of money waiting for a change of government to invest.”

Data tell a similar story. Foreign portfolio investment surged into Brazil during 2021 and most of this year. Looking at the capital flows to Brazil from foreign investors relative to the rest of Latin America, “the picture is not very different from what we have seen in the early 2000s”, says Martín Castellano, head of Latin America research at the Institute of International Finance. He noted that “the pick-up in foreign direct investment in Brazil has been quite remarkable” — it soared to $73.8bn in the year to September from $49.9bn a year earlier.

Luis Oganes, global head of emerging markets research at JPMorgan, says that the share of Brazilian local bonds held by foreigners has been stable since the end of 2020, while declining in other Latin American markets.

“There have been important inflows into Brazilian equities in the first quarter of 2022 and in August and October,” he adds. “Part of this is because of high commodity prices.” The Bovespa index has gained some 16 per cent over the past year, leaving the market priced at 8 times trailing earnings.

How could ESG-conscious investors put money into Brazil while deforestation surged and a hard-right president railed against gays?

Many asset managers use broad data sets to screen investments against ESG criteria and despite the Amazon destruction under Bolsonaro, Brazil scores well for clean energy (most electricity is generated from renewables), vibrant democracy and a free press.

Lula’s promise to crack down on deforestation has raised hopes that he will repeat the environmental success of his first two governments from 2003-10. But whether Lula will make good on his pledge to “reposition Brazil in the hearts of international investors” is a different matter.

The new president has pledged to scrap a constitutional cap on government spending to boost welfare payments. He has promised to be fiscally responsible but has not yet said how he will pay for his expensive promises from a stretched budget in a country that already has one of the region’s highest tax takes.

Investors in the state-controlled oil company Petrobras have reason to be wary. During the last government run by Lula’s Workers’ party, the debt burden of Petrobras rose to $130bn by 2015 and the company suffered from mismanagement and corruption scandals. Its American depositary receipts have fallen 4.9 per cent over the past month.

Saverio Minervini, head of Latin America energy at Fitch, has analysed the risks to Brazil’s national oil champion under Lula and says “leave Petrobras alone”. “There’s no economic rationale for the government to influence Petrobras because the government stands to get almost 1.5 per cent of GDP in [tax and dividends] from Petrobras.” Minervini believes Lula’s plans for new oil refineries would cost the company $20bn-$30bn.

Petrobras will be closely watched as a bellwether under Lula. It will also serve as a reminder that despite ESG pledges, most investors in Brazil remain focused on the fundamentals of economic policy.

“Beyond environmental pledges, I think that what will be key for investors to increase their investments in Brazilian bond and equity markets will be a credible plan of fiscal adjustments,” says JPMorgan’s Oganes.

Comments