Inside the home of Sally Davies, England’s chief medical officer

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Spend a few minutes in the company of Dame Sally Davies and you will soon hear her personal mantra, “The evidence says . . . ” crop up in conversation. As England’s chief medical officer, she needs facts and figures at her fingertips. Since 2010 Davies has been the most senior adviser to the government on medicine and public health and has made full use of her position to bring scientific evidence directly into the heart of the debate at Whitehall. “It’s my job to explain the science and take them [the politicians] with me. It’s a fun challenge,” she says.

Davies, 65, and her husband, Willem Ouwehand, a professor of experimental haematology at Cambridge university, bought their north London townhouse 25 years ago, soon after their marriage in 1989. In the early days, when the couple’s two daughters were young, they rented out the basement and lived with threadbare carpets to make the place affordable. But 12 years ago, keen to complete the Victorian home’s transformation from “scruffy to rather nice”, they commissioned the London-based architect Andrew Yeoh to design a striking rear façade. The exterior wall, from the first floor to the garden, two storeys below, was removed and replaced with huge slabs of plate glass.

“We work like crazy, but we live and we have parties here,” says Davies, as she leads the way into the open-plan sitting and dining area. A beautiful Purbeck marble floor flows into a long galley kitchen, with well-stocked cupboards, and Davies says she enjoys cooking in her spare time. With three important jobs (she also heads the National Institute for Health Research, and sits on the World Health Organisation’s executive board), I wonder how she has the patience for the slow arts of bread baking and jam making but she describes these activities as “energy making” and emphasises the fact that she is “extraordinarily well organised”.

On at least two mornings every week, Davies rises at 6am to exercise. Every few months it seems evidence emerges showing that regular exercise reduces cancer risk, bolsters mental health and improves quality of life, and an awareness of the nation’s physical activity, or lack of it, can keep her awake at night. She recommends that adults are on the move for at least 150 minutes a week. “It doesn’t matter how you do it, just do it. Get off the bus two stops early or cycle to work. Do your own housework,” she says. “You’re better being fit and a bit fat, than skinny and unhealthy.”

But despite her influential position, Davies’ first instinct is to avoid prescriptive, top-down solutions. Rather, she wants to empower people to take responsibility for their own health and build a healthcare system that is proactive rather than reactive. “Behaviour change always starts with understanding,” she says. She wants people to understand that alcohol is a big source of hidden calories and a direct contributor to cancer, for example, but she does not want to be a killjoy. To those couples around the country who find themselves getting through a bottle of wine most evenings her message is simple: “make the bottle last two nights and don’t drink every night”.

Yet, Davies is not afraid of confrontation. She recalls hearing someone high up in a cola-drink company claim that people need their drinks to live. “Rubbish,” Davies snapped back at him, “we need water.” Through straight talking and robust defence of the facts, Davies has encouraged several food industry players to improve labelling and to reduce the salt and calorie content of some of their products. But if these voluntary actions don’t go far enough, she is open to the idea of bringing legislation to bear. “We may need to move towards a sugar tax,” she says, “although nobody has worked out how to do that or even whether it would work as intended.” Her role as chief medical officer is not a political appointment, but time will tell whether Britain’s new government will favour a more interventionist approach to public health.

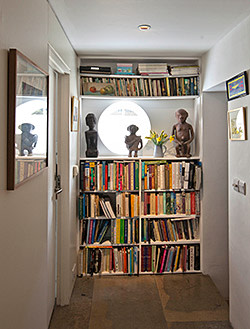

Davies’ personal interests are broad and wide-ranging. Nearly every surface and wall inside the house displays intriguing artworks and artefacts from around the world. Tuareg masks, Burmese puppets, Ashanti fertility figures and Ladakhi-Buddhist images are interspersed with European abstract paintings, Afghan ceramics and Nigerian statuettes. They have been collected over years on holidays and work trips, and every one has “a story to tell”.

Favourite thing

“With my clutter, the problem is in choosing a special object,” laughs Davies. She plumps for a small vase that sits on the bedroom mantelpiece. It was a present from the Canadian chemist and part-time potter David Dolphin. The swirling rusty pigments of the glaze are rich in iron, the key element that red-blood cells need to transport oxygen around the body. It reminds Davies of her roots at the frontline of haematological care.

International health issues are another concern, and Davies played a key role in co-ordinating the UK’s response to the Ebola outbreak in west Africa last year. She is proud of the altruistic British volunteers, doctors, nurses, laboratory staff and government officials who “went out there and put themselves at risk to do a fantastic job,” and she wants to ensure we learn from this event so that the global community can react more promptly and efficiently next time. “There is a strong economic imperative to do so, but also a clear-cut moral obligation,” she adds.

Davies was raised in Birmingham; her father, John Davies, was a theologian and a prolific scholar, and she grew up with a strong moral code of right and wrong. Studying medicine at Manchester Medical School was her first step towards “making a difference”, but her rise through the medical ranks was far from seamless. After marrying her first husband, Davies stopped doctoring altogether and moved to Madrid, where she lived as a diplomat’s wife.

Four years later she came back to Britain and returned to medical practice. Her first marriage ended in divorce, and although she remarried in 1982, her second husband died within months.

In 1985 Davies was made a consultant haematologist at Central Middlesex Hospital. For 25 years her main focus was on sickle-cell anaemia, a crippling genetic disorder of the red-blood cells that is relatively common in people of African origin, but often neglected by western medical practice.

In Davies’ ground-floor office, which connects to a formal sitting room, she talks passionately about another global issue: the accelerating spread of bacteria with resistance to antibiotic drugs. “I liken it to climate change. But it will kill us off before climate change if we don’t do something about it,” she says. Politicians are heeding her words, and she applauds the £195m Fleming Fund, announced in the pre-election Budget, to improve global disease surveillance and response capacity. Yet in line with the recommendations published this month by Jim O’Neill’s UK government-appointed antimicrobial review committee (“It was my idea to do it”, says Davies), she stresses the urgent need for further reaching and more concerted international action.

We move upstairs, and into the couple’s large bedroom, which is kept dark to protect Davies’ fine collection of 19th-century watercolours — she has been collecting them for years and inherited several of the more expensive works from her father. Davies proudly points to the books he wrote, which fill two shelves of a bookcase on the landing.

Although Davies is the first woman to act as the government’s chief medical officer, she is not convinced that her gender brings anything special to the role beyond “the willingness to take a more collaborative approach, and perhaps a relative lack of ego”. But she acknowledges that her achievements could inspire many younger women. In recent years she has become a more outspoken advocate for female doctors and scientists. “I argue that it’s an economic issue: what are we doing with half of our best brains?” she says.

From her continuing project to de-stigmatise mental health to the launch of the National Institute for Health Research, Davies is pleased with some of what she has achieved by bringing scientific evidence to the public sphere.

Yet she acknowledges that not everything is amenable to rational scrutiny. She can provide no evidence, for example, to explain the source of her prodigious energy. “If I could package it, I’d be rich, wouldn’t I?” she laughs. Nor does she have any plans to rein it in any time soon. “My ambitions are all about making a difference. I’m more interested in influence than power,” she says. “I want it all to work.”

Photographs: David Sandison

Comments