Sandfuture by Justin Beal — Minoru Yamasaki’s demolished dreams

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Minoru Yamasaki will always be remembered for explosive collapses. The architect of the World Trade Center, which on September 11 2001 became the target of the world’s most stunning terrorist attack, Yamasaki was also responsible for the failed Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St Louis, which was dynamited between 1972 and 1976.

He is now, in a way, an architect of absences. The footprints of the Twin Towers are now two gaping, black holes with water gushing into their depths. The site of Pruitt-Igoe is, incredibly, still vacant and now covered in trees and vegetation, a kind of uncanny urban forest.

Justin Beal’s book is a work of literary non-fiction that attempts to outline the life of Yamasaki (1912-86), punctuating it with biographical detail and leavening it with digressions about everything from migraines and air-conditioning to climate change and the history of sanatoriums.

It is not like any other book on architecture I have read. And that is a very good thing. Beal is not an architect, an academic or a writer but an artist with architectural training who, handily, can really write. He joins some very disparate dots, skirting around the history of Modernism, its successes and failures.

An American-born architect of Japanese descent, Yamasaki proves a perfect frame for the extremes of 20th-century America; racism, corporate capitalism, consumerism, an over-reliance on technology, sick building syndrome, inequality, gentrification and much more.

Yamasaki was hugely successful yet plagued by a sense that his alienness was holding him back. That he built airports, offices, embassies and what were then the tallest buildings in the world somehow failed to quell that nagging inadequacy.

When architectural historian Charles Jencks wrote in 1977 that “modern architecture died in St Louis, Missouri, on July 15 1972 at 3.32pm (or thereabouts)” he determined Yamasaki’s fate. His failure was to be the failure of a movement, the laudable ideals of which had been debased on contact with reality.

Beal makes the point that Jencks’ assertion was shoddy history: it was the wrong day, the wrong time. Nevertheless, it stuck. Yamasaki, despite having completed the world’s tallest towers, was tainted. He became the representative of a debased, commercialised Modernism shorn of its social intentions.

The project, by its end an ill-maintained slum populated by the poorest of St Louis’s black population, had its architect’s most sophisticated features — the social spaces, the landscaping and playgrounds — value-engineered out. The exploration of its construction and rapid decline is as fascinating as the story of the WTC, which was built on reclaimed land, launched into a commercial climate that had no need for more office space and designed as two dumb slabs framing a bleak public space. They were unloved when they opened and, though attitudes softened, they were never held in any real affection until after they were gone.

Beal’s research into Yamasaki’s life reveals a sad, insecure alcoholic workaholic. He seems to embody the mid-century ideal of the hard-working, hard-drinking creative mythologised in Mad Men but without any of the swagger or enjoyment. He was based in Detroit, not New York, and, having worked his way through college with brutal shifts at an Alaskan fish cannery, he proceeded to slog through work, whiskey and wives.

Yet, although Jencks made him a cipher for the failure of Modernism, you could argue Yamasaki was a proto-Post Modernist. His often delicate buildings (such as Saudi Arabia’s Dhahran Airport, now King Abdulaziz Air Base) frequently employed decoration (even the WTC had its ogee arches) and he attempted to humanise the scale of modern construction with lightness and even humour. The architectural establishment mostly ignored him.

Beal flits fitfully between Yamasaki’s sparse archive, the gentrification of Chelsea, where his life partner had a gallery, its flooding during Hurricane Sandy and the rising tower at 432 Park Avenue, a brilliantly abstract extruded grid by Rafael Viñoly that perfectly expresses the absurdity of New York real estate, as much a graph of value as a real building.

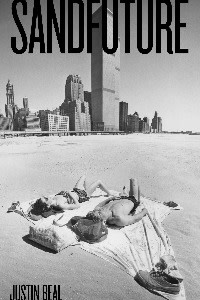

Sandfuture ends up being a story about failure wrapped in apparent success, and the financialisation of a city, the poorer edges of which are washed by rapidly rising seas. Its unsettling cover photo of a couple sunbathing in 1977 on the temporary beach where Battery Park City would be built encapsulates this notion of monoliths built on shifting sands, coming from nowhere and now gone again.

Beal has written a brilliant, often surprisingly personal, book that works as metaphor and, perhaps, as portent.

Sandfuture by Justin Beal, MIT Press $24.95, 256 pages

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture and design critic

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café

Letter in response to this article:

Don’t blame the architect for Twin Towers’ collapse / From Sandor Vaci, London SW1, UK

Comments