UK can help shape a better future for Africa’s children with its wallet

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In Africa, there has never been a better time to be alive.

The past two decades have seen steady improvements, to the extent that a child born in Africa today has a better chance than ever of living longer, avoiding extreme poverty, receiving a primary school education and joining a growing economy.

Yet not all the movement is in one direction. The Covid-19 pandemic is having a profound impact, forcing much of Africa into recession. While the continent’s long-term outlook for growth remains positive, too often the expansion is inconsistent, fails to create jobs and delivers benefits that do not trickle down.

There is inconsistency, too, when it comes to governance — the issue that ties it all together. Without good governance, and without transparent, trustworthy and democratic leadership, social and economic gains are wasted. A good year can quickly be followed by setbacks and backsliding.

That said, the past decade has broadly been a period of improvement. In 2019, a little over 60 per cent of Africa’s 1.3bn people were living in a country where overall governance, as measured by the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, was better than in 2010.

Clearly, I am an optimist and there are good reasons to be optimistic. But we must also be realists.

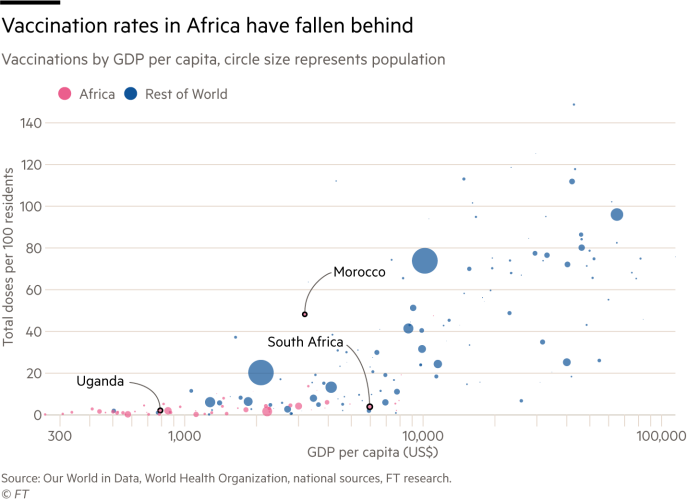

While some economies in Europe and the US are already bouncing back from the pandemic, with vaccination drives that have covered 60-70 per cent of their adult populations, Africa is still waiting. Its leaders deserve credit for enforcing lockdowns and limiting infections, but they have struggled to get hold of vaccines.

By the start of June this year, only 32m vaccine doses had been distributed across Africa. While Covax — the multilateral programme to deliver vaccines to poorer countries — is responding to the challenge, and the G7’s pledges of assistance will no doubt be a boost, this is all too little, too late.

It is too early to count the full cost of the pandemic for the continent. But this year’s Ibrahim Forum Report on Covid-19 in Africa highlights how it is only likely to deepen inequalities and impose deep costs on governments ill-equipped to handle the shock. The knock-on impact will be fewer resources — not only for health but also for areas such as education, training and investment, which can lead to frustration and anger, and an increased risk of unrest or conflict.

In many African countries, children have missed out on months of education and social contact. At home with few resources, they have gone hungry, missed health check-ups, and been exposed to greater risk of violence and abuse. If home-schooling has been a struggle in the richest countries, think what a profound challenge it has been in Africa.

It is at moments like these that governance comes to the fore. The pandemic is an unprecedented test of leadership, one that many African leaders have stepped up to. But they can’t rest on their laurels. Every day brings new, harder decisions that will shape outcomes for generations.

On public health, on education, investment and even tax policy, leaders must act intelligently at a national, regional, and continental level. They need to seize the opportunity to introduce policies that provide better protection for their populations as they weather the pandemic and emerge from it. And they must be joined in that effort by partners globally that understand the continent and want to ensure that aid and development are seen as an investment in the future, not an emergency stopgap.

This is where Britain and its allies need to think strategically. Investment that commits to the future is the sort that will reap benefits for Africans — in terms of jobs, growth and deeper engagement in the global economy. It will also benefit investors — in terms of a return, stronger trade links and better long-term relationships.

By 2030, a fifth of the world’s population will be from Africa. Every year, tens of millions more young people from the continent join the labour market. They need the skills and training that allow them to realise their potential. Young people are our continent’s greatest asset, but if we do not create opportunities for them — to learn, to find work, to be productive — we risk losing them as they migrate to places that can deliver what they are looking for. An estimated 80 per cent of young Africans who migrate do so because of a lack of work.

I have no doubt Africa can overcome these challenges. But leaders need to take sound decisions, and countries such as Britain need to stand with them.

Recent cuts to the UK’s aid budget are a serious concern. This is not a time for a generous donor such as Britain to be scaling back — especially if it wants to live up to its Global Britain label. The latest decision, cutting aid to Africa by two-thirds, from £2.2bn in 2020 to just £760m this year, cuts through the bone. The consequences far outweigh the money saved for the UK.

The pandemic is a crisis for Africa, as it is for the world. But, like every challenge, it presents opportunities. With the right decision-making, the ground can be laid to strengthen education, investment, jobs and trade. When you look at the youth and dynamism in economies including Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia and Ghana, only a fool would write them off.

Young citizens in Africa crave opportunities. Whether it’s in the digital economy, the green transition, resources, energy or infrastructure, Africa and Africans have a role to play. Britain shouldn’t miss out on the opportunity to make it happen.

Mo Ibrahim is founder and chair of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which he established in 2006 to support good governance and exceptional leadership in Africa. Sudanese-born, he was the founder of Celtel International, one of Africa’s leading mobile telephone companies.

Read his full essay on the Unicef website, here

Comments