Investors risk losing faith in returns on offer from ‘Big Oil’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When BP chief executive Bob Dudley warned late last year that divestment campaigns threatened to “drive a wedge” between the energy industry and investors, his appeal was to the hypothetical risk of starving a critical industry of capital long before the energy transition is completed.

Oil and gas, the argument goes, will remain a major part of the energy mix and demand will keep rising for at least another decade, meaning that without continued investment in new supplies the global economy could be threatened by shortages.

But while Mr Dudley’s focus was divestment, which primarily argues the environmental case for fund managers and financiers to turn away from oil, at the start of 2019 the industry arguably faces a far more immediate problem.

Investors, regardless of their environmental view of “Big Oil”, appear to already be losing faith in an industry roiled by both short and long-term challenges that few are certain how will play out.

The problems range from the prosaic to the existential; lower oil prices brought about by the rise of the US shale industry, which has flipped the supply outlook in many minds from one of scarcity to abundance, has damped the short-term investment case. Longer-term, there are fears about how the industry will fare if, as increasingly forecast, oil demand does peak in the 2030s.

“There’s just this hate for this commodity right now,” said Bernstein analyst Bob Bracket.

“They don’t want it in the short-run due to the price swings seen in recent years. And in the long-run there are fears about how these companies look in a decade’s time, if the energy transition gathers pace.”

The question, at its heart, is whether investors still feel they need to bother with oil and gas when there are so many other opportunities available to them.

That has left oil and gas companies trading at some of the lowest multiples ever seen relative to the profits they are still generating, with investors increasingly rejecting both the short and long-term investment case. While shares of companies like BP and Shell remain key components of UK pension funds, energy-focused hedge funds were some of the worst performers in the sector last year.

While this may be music to the ears of the divestment community Mr Dudley targeted with his ire, some hard-headed money managers think that instead it presents them with a great opportunity.

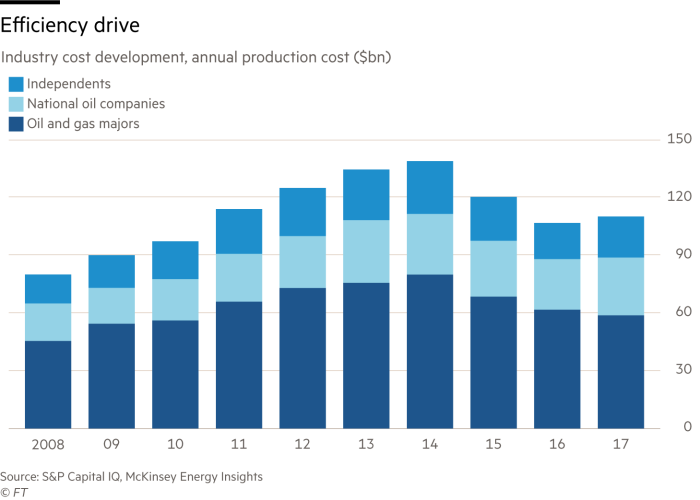

While the risks highlighted above are clear, if oil and gas companies can continue generating profits, helped by their success in driving down costs in the last five years since prices slumped from above $100 a barrel, they may still prove a cash cow for investors who buy in when they look relatively cheap. Long-dated oil prices have stabilised, with Brent crude for delivery in 2025 trading just below $65 a barrel — not as exciting as the go-go era of $100 a barrel crude a the beginning of this decade, but still high enough for most companies to comfortably earn strong returns.

“There’s a bit of a disconnect as investors are struggling with the volatility and uncertainty,” said RBC Capital Markets analyst Biraj Borkhataria.

“But these are major companies that are likely to continue generating cash for investors for many years to come, and no one knows quite how the energy transition is going to play out just yet.”

The investment case is based, in part, by a growing expectation oil companies will need to keep dividends high to keep attracting uncertain investors. With concerns about long-term demand for oil percolating, they are also seen as less likely to pursue the type of ambitious, highly complex projects such as Arctic exploration that have so often proved a sinkhole for investors’ cash.

Mid-sized oil companies in particular, including those involved in the US shale patch, may need to focus more on shareholder returns rather than rapid expansion.

Nick Stansbury, who heads Legal & General Investment Management’s strategy in commodity markets, said the entire industry needs to keep its focus on investors.

“It’s getting harder and harder to attract capital into unloved sectors, and oil is definitely unloved. I don’t think this is a short term phenomenon, even if the particularly extreme valuation anomaly we’re seeing now corrects itself in the coming months.

“The structural challenges the industry faces aren’t going to go away, so energy companies of all sizes need to clearly articulate how they will allocate investors’ capital and prioritise shareholder returns in a manner that rebuilds confidence.”

Some investors say it also makes sense to hold traditional energy stocks as a hedge for those who are increasingly ploughing money into renewable energy projects, should oil and gas companies end up outperforming newer forms of energy.

The energy majors themselves are also spending more on diversifying their businesses as part of the energy transition, branching beyond oil and gas to invest in renewables and businesses like electric utilities they see benefiting from the shift towards electric cars.

Mr Bracket at Bernstein, who acknowledges the long-term uncertainties around investing in traditional oil and gas companies, nevertheless says he has taken to adapting the old maxim made popular by Warren Buffett: that the time to be greedy is when everyone else is running scared.

“You know what we’ve taken to telling investors: ‘Be oily when others are fearful’.”

Mr Dudley at BP will hope enough investors can be convinced to run against the herd.

Comments