Why housing is the key to the next Fed pivot

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is co-founder and chief investment strategist at Absolute Strategy Research. David Bowers contributed to this article

Investors are desperate for signals about any “pivot” by the Federal Reserve. It may be that US housing will be more important in forcing the Fed to ease than either inflation, or unemployment.

Over the last century, housing has helped define the swings in the economic cycle, being a key driver of investment, employment, and consumption (especially white goods). As one recent research paper put it. “Housing IS the Business Cycle”.

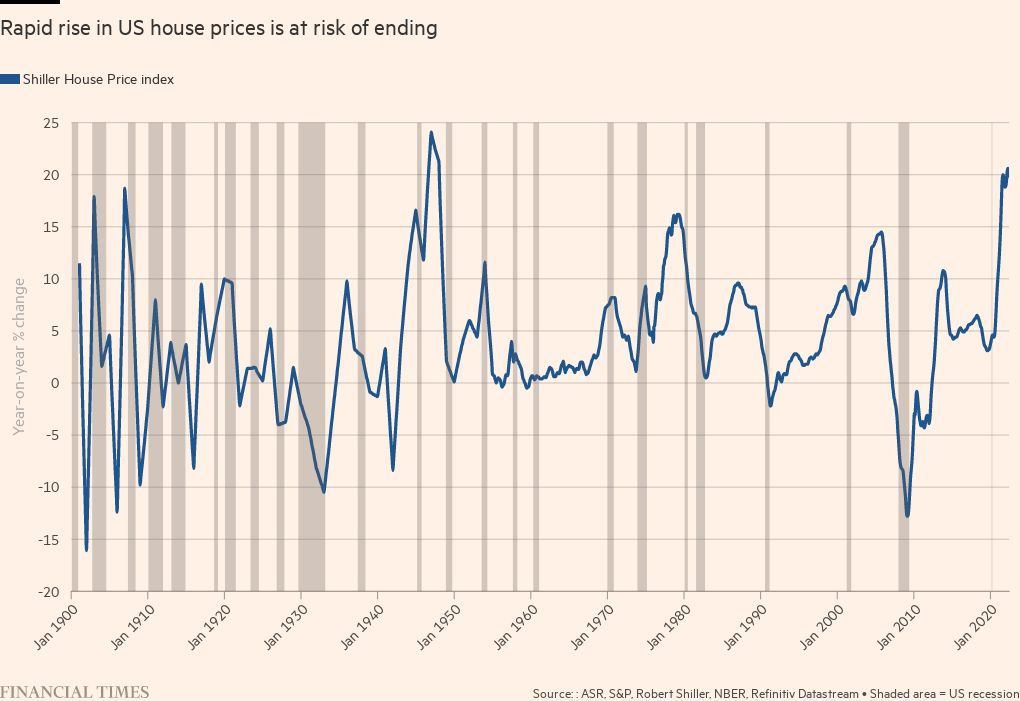

Easy monetary and fiscal policy, post-pandemic, has helped fuel 20 per cent US house price inflation (the fastest seen since December 1946). Three-year house price inflation of 46 per cent in nominal terms and 28 per cent in real terms has only been matched by the bubbles of the early 1980s and mid-2000s in the past 70 years. However, these “good times” for US housing look to be ending as property faces a perfect storm of rising financing costs, squeezed demand and increased supply.

Investors often focus on mortgage rates and refinancing activity as key drivers of housing demand, but trends in real income tended to play a bigger role. These are being squeezed by the rise in CPI inflation. The US house price to income ratio is now at a postwar high of 4.8x, and with financing costs rising, affordability is at its lowest since just before the subprime crisis. Consumer confidence about this being “a good time to buy a house” is now lower than at any time since 1980. But just as demand is being challenged, the potential supply (homes started but not completed) is at record highs.

The consequences of this demand/supply imbalance are beginning to emerge. New home sales of 511,000 in July were down almost 50 per cent from two years earlier. At the same time, the National Association of Home Builders index has fallen faster this year than at any time other than the start of the pandemic.

The importance for the real economy is that new home sales lead housing starts. If starts slow by 600,000 in the next 12 months to below 1mn (as our models suggest), this could cut about 1.5 per cent from US gross domestic product.

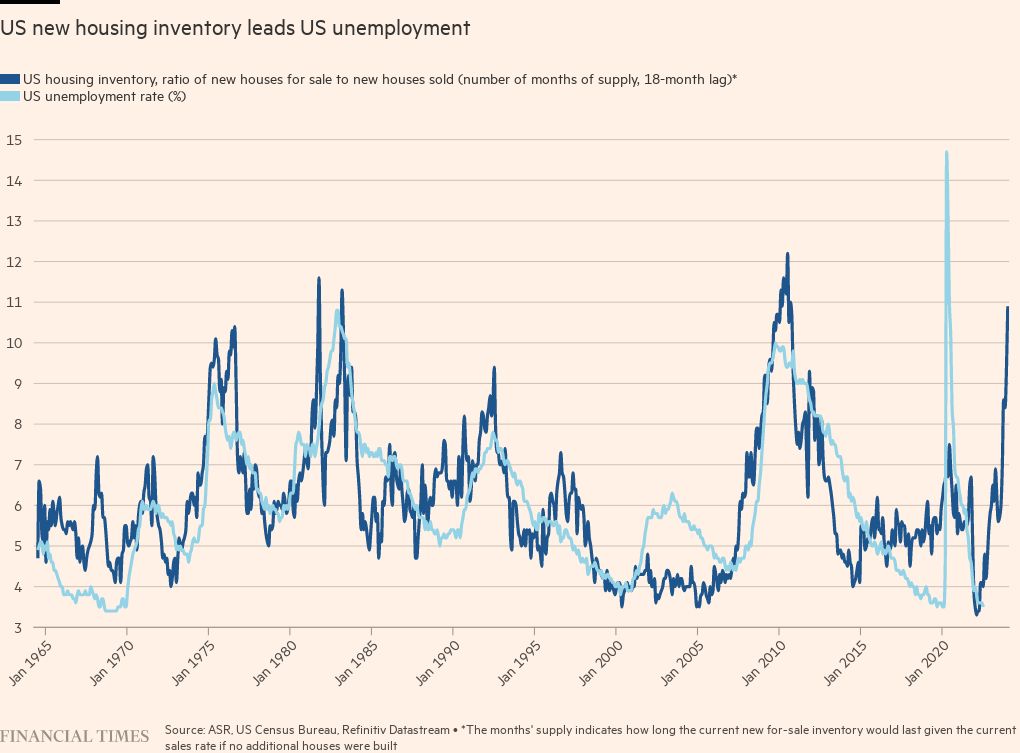

Slower new home sales pushed the inventory/sales ratio up to 10.9 months of supply in July. These inventories typically lead unemployment, suggesting that the unemployment rate could be more than 5 per cent in 18 months’ time — definitely not the “soft landing” hoped for by many investors.

We hear two main counters to this narrative: first, low existing-home inventories constrain current supply, and second, healthy consumer balance sheets limit any demand risk.

While the existing-home inventory is currently low, at only three months’ supply, the changes in new-home inventories lead existing-home inventories by three months, suggesting the inventory of existing homes could increase quickly by the end of 2022.

While household balance sheets remain strong, historically this has been no protection against recession. Strong balance sheets were often seen prior to previous recessions. Also, consumer confidence about their financial position is worse than any time other than the global financial crisis. The reality is that the bulk of this wealth is owned by a minority of higher income households.

The investment consequences of housing downturns are many. Equities suffer as new home inventories rise, the economy slows, unemployment rises, and profits go into reverse. Housing-related equities and commodities struggle.

But the key market risks from this housing cycle are likely to lie with those non-bank mortgage lenders central to funding the post-crisis housing boom. However, these risks multiply if the slowdown in house prices spreads into commercial real estate (as it has tended to in the past 70 years), potentially posing broader risks to US financials and “alternative” assets.

In conclusion, US housing is central to both the real economy and financial markets, making it potentially critical to the timing of any Fed pivot (perhaps more so than either inflation or unemployment). Historically, US rate cycles typically only turn as the Fed is forced into easing by financial crisis. It is unlikely that this time will be different.

Given the importance of housing for the US economy and markets, perhaps it is time for the Fed and other central banks to follow the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, and explicitly add housing into their policy mandates. After all, housing is the business cycle.

Comments