Romania must avoid association with Europe’s ‘bad boys’

Simply sign up to the EU economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The second world war did not truly come to an end in Romania until the anticommunist revolution of 1989. Such is the contention of Dennis Deletant, one of the world’s leading scholars of modern Romania, in Hitler’s Forgotten Ally, his 2006 book on Ion Antonescu, Romania’s military dictator in the early 1940s. The nation’s disastrous wartime alliance with Nazi Germany was followed by more than 40 years of vicious communist rule that left Romania one of the poorest and most atomised societies of eastern Europe.

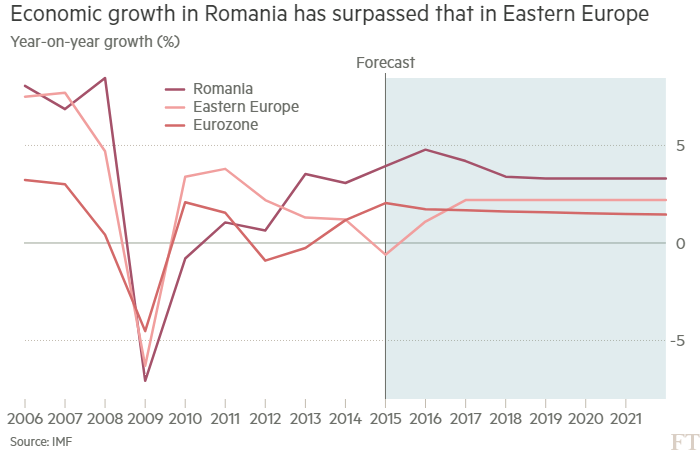

Only against this historical backdrop is it possible to appreciate the admirable strides Romania has made, despite its shortcomings and self-inflicted troubles, over the past quarter of a century. Burdened with a fragile democratic record before 1939, destitute and isolated under Nicolae Ceausescu, the communist dictator from 1965 to 1989, Romania today is a more open, outward-looking society that is increasingly confident in its European skin. A Nato member since 2004, Romania joined the EU in 2007. In the first half of this year, it boasted being the bloc’s fastest-growing economy.

In order to secure Romania’s future prosperity and stability, the nation’s political classes, business leaders and society as a whole will need to demonstrate the will and ability to engage in the next phase of Europe’s development. Germany and France, supported by other western European countries, are gearing up for a new effort at the economic, financial and perhaps even political integration of the eurozone. At the same time, western European governments are impatient with what they regard as the provocative behaviour and undemocratic tendencies of certain central and eastern European states, especially Hungary and Poland.

For Romania, it is a fundamental national interest not to be relegated to some diplomatic and economic backwater of Europe where, as so often in its history, it would be at risk of being manipulated by greater powers, including Russia. Two consequences flow from this. First, Romania must uphold domestic democratic standards and the rule of law in such a way that it will not be bracketed with the “bad boys” of the ex-communist half of Europe and thereby lose influence in the EU. Second, Romania must continue to strengthen its public finances, business competitiveness and other areas of economic performance to the point where it could one day join the single currency.

Naturally, Romania must not try to run before it can walk. If a country acquires eurozone membership before it is ready, there exists the danger of an economic catastrophe — as Greece, Romania’s fellow Balkan state, can testify. Nonetheless, 19 of the EU’s present 28 states are in the currency union. With the UK poised to leave the EU in March 2019, Romania is set to be part of a shrunken group of eight non-eurozone states. Their voices may be heard less loudly in Brussels, Berlin and Paris.

This prospect is of obvious concern to Romanian policymakers — and they would do well to learn the lesson of Greece’s experience. A year before it adopted the euro in 2001, Greece was deemed to fulfil the EU’s headline criteria for eurozone entry, covering inflation, budget deficits, public debt, exchange rate stability and long-term interest rates. Yet none of this put Greek membership of the eurozone on a solid, durable foundation. Neither would it, for the foreseeable future, in Romania’s case.

As in Greece, the real questions are whether Romania’s political culture can fully purge itself of corruption and cronyism; whether the rule of law can prevail over opaque networks of politically connected private interests; and whether public institutions are strong enough to defend themselves from political pressure. As Greece discovered, eurozone membership exacts a punishingly heavy price from a country where state institutions and the law are hostage to political party interference and where a system of clientelism operates in which government contracts are awarded only to those with the right connections.

Over the past four years, Romania has made more progress in clamping down on corruption among its political and business elites than some outsiders would have imagined possible. Brave, determined individuals at Romania’s anti-corruption directorate deserve credit for this, as does President Klaus Iohannis, who since his election in 2014 has proved to be a staunch defender of high standards in public life.

Unfortunately, these same four years have also traced an unmistakable pattern of attempts on the part of influential politicians to neutralise the anti-corruption effort. After mass street protests erupted in February and forced the government to withdraw a decree that would have decriminalised some acts of corruption, it seemed plausible to argue that Romanian society had come of age and would no longer tolerate flagrant abuse of power by the political classes. There is indeed a heightened sense of disgust among young, urban Romanians as regards official corruption.

Yet in August the government proposed new measures aimed at shaking up Romania’s judicial system. Under the proposals, the president would no longer have the right to name top-level prosecutors, including those attached to the anti-corruption directorate. The proposals would also reduce the directorate’s powers so it would not be able to investigate magistrates. Both the European Commission and the US embassy in Bucharest expressed concern that the proposals would undermine the independence of the Romanian judiciary. The US embassy warned that “establishing the rule of law requires a strong and independent judiciary, as well as independent prosecutors who can pursue criminal conduct without political interference”.

The political elites that emerged from Romania’s post-1989 transition to democracy and capitalism exercise a tight grip over public life. Increasingly, however, these tainted elites do not meet the aspirations of the generation of Romanians born just before and after the fall of communism. The question is when, and to what extent, this generation will have the chance to take on the responsibility of ensuring that Romania plays a full, constructive part in Europe’s future.

Try the FT’s dynamic country data dashboard

Romania: news and data

See the latest Romanian business and finance news, alongside economists’ forecasts for GDP, inflation, current account and the leu-euro exchange rate — all in one place

Comments