The Silver Economy: Financials bank on elderly for new revenues

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A few years ago, HSBC was caught selling long-term investment bonds that might never pay out to elderly customers as old as 93. There was a scandal and a humiliating £10.5m regulatory fine for the UK’s biggest bank. Similar stories have since unfolded at Santander and Barclays, deterring lenders from focusing on such a sensitive segment of the population.

“There is a danger that the older generation becomes underserved because the regulatory risk is too high and that is a shame,” says Steve Pateman, head of UK banking at Santander.

The timing could not be worse. Faced with a bleaker profit outlook in the wake of the global crisis and with new technology disrupting old ways of doing things, many banks, insurers and asset managers are desperate for new sources of growth. At the same time, an ageing population does have a genuine need for better products and services.

In mid-September in Milan, Federico Ghizzoni, UniCredit’s chief executive, called a summit of 30 of the bank’s top staff for a day of brainstorming. Italy’s biggest bank was keen to grasp the challenges and opportunities of an ageing customer base in a country where dramatic social reforms, including brutal cuts to a once-generous state pension system, are under way.

“Our customer base is getting older,” says one person who was there. “That is both an extreme challenge and a big opportunity.”

UniCredit now has a special committee to follow through on the ideas generated there and two initiatives are already in train. In its investment advisory business, the bank is training 2,000 of its staff as home-visit relationship managers, mitigating the need for elderly customers to visit branches. Its wealth management unit, meanwhile, is focusing on extended families to increase the chances that children and grandchildren of ageing customers might become important clients when they have wealth in their own right.

Wealth management, for the obvious reasons of large revenue potential, is a hotspot for banks’ focus and fresh thinking.

Among the most striking innovations in the area is a new smartphone app launched by Merrill Edge called Face Retirement. Any customer with a webcam can tap on the app and watch themselves age on screen.

“Preparing for retirement is easier when it’s staring you in the face,” the Merrill Edge website tells visitors.

With a growing pool of older customers and a stagnant or even declining pool of workers, the question for the wealth management industry is how to expand assets under management and by extension the fees that are the sector’s bread and butter.

Kathryn Koch, head of global portfolio solutions international at Goldman Sachs Asset Management, says the combination of an ageing population and a shift towards greater individual responsibility for retirement savings is creating plenty of new opportunities. “The more time you have until retirement, the higher your ability to take risk should be,” Ms Koch says.

Goldman is one of a number of banks, including Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley, that are seeking to offset the risks in their core investment banking businesses by attracting more affluent customers, many of whom are retired or close to retiring, to boost their asset management activities.

Other fund managers have gone a step further, targeting investment in companies that are best placed to benefit from the surge of older people in the world’s richest countries as well as the fast-growing middle classes of emerging economies.

Johan Utterman, portfolio manager for Lombard Odier’s Golden Age Fund, says the bank is attracting new investors by emphasising the fact that population change is a certainty, unlike the vagaries of oil prices or inflation that can overwhelm sector-focused investment strategies. “You know these trends are happening for sure,” he says.

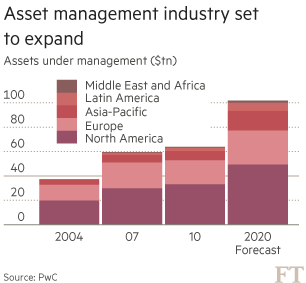

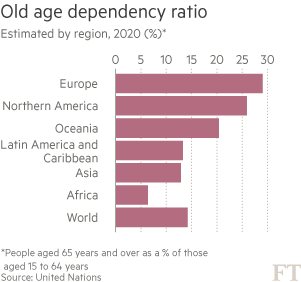

The number of people over 65 is set to double in only 25 years from 600m to more than 1.1bn, according to the UN’s latest global population forecasts. As the world ages, and people need to save more for retirement and healthcare, the asset management industry is expected to expand from $64tn of assets under management to $102tn by 2020, according to PwC.

The demographic shift will be most dramatic in Japan, which is expected have 69 old people for every 100 of working age by 2035. In response, Japanese banks have been putting on special services for older customers, such as inheritance seminars for elderly clients and their children, a will drafting kit and donation services.

FT series

How industries ranging from technology to entertainment are waking up to the opportunities provided by the world’s rapidly ageing population

Further reading

“Inheritance tax will increase next year in Japan, so we are offering an inheritance service with our partners and organising inheritance seminars across the nation,” says Masahiro Yamasaki, vice-president of product development and planning at Nomura Securities. “This is a very big issue,” he says, adding that the annual value of inherited assets in Japan is about Y50tn ($487bn).

Many people are not planning or saving enough for retirement, as illustrated by an HSBC-sponsored survey of 15,000 people in 15 countries published early this year, which found that one in eight people expect to never be able to afford to retire.

This should be an opportunity for pension companies and insurers. One of the most powerful trends looks set to be the increasing use of the latent value of property to boost retirement income.

UK insurer L&G reckons £1.3tn of wealth is tied up in the homes of Britons over 65. For many people, the house they live in is one of the few assets they own and certainly one of the few to have increased markedly in value in recent years. That has prompted growth in the market for what are termed reverse mortgages in the US, or equity release mortgages in the UK.

A poll by Baring Asset Management recently found that a record 7 per cent of Britons planned to sell their home to fund their retirement. But Rod Aldridge, head of BAM’s wholesale distribution business, warns that the trend may be going too far.

“It is worrying that the number of people relying exclusively on their property to fund retirement has increased again . . . Property prices can be volatile so relying on your home to provide all your income to fund retirement is risky.”

Reporting by Martin Arnold, Patrick Jenkins and Norma Cohen

Comments