Lunch with the FT: Edmund de Waal

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

“I can’t believe we’re having a picnic in this place,” says Edmund de Waal. The prospect before us does look like something out of wonderland. In a huge, double-height, white-cube art gallery, a tiny table for two is set in a corner beside a vast glass wall giving on to golden sands and rolling waves. On a tablecloth decorated with boats stands a bottle of red wine, a Thermos flask, tin plates in pink and gold Coalport Sevres design, linen napkins wrapped around silver cutlery, a pile of roast salmon sandwiches, and a platter of vacherin and Montgomery’s cheddar. An azure menu card promises “A Picnic by the Sea”; a tartan rug awaits should we wish to relocate to the beach.

Midway through installing his new commission for Turner Contemporary in Margate, which opens March 29, the ceramic artist has agreed to break for lunch – ordered from a favourite deli close to his south London studio, as it is Monday and the museum’s café is closed. In jeans and a blue shirt with a hard hat to hand, de Waal is scrambling about a giant scissor lift when I arrive, but he leaps up to greet me with a hug.

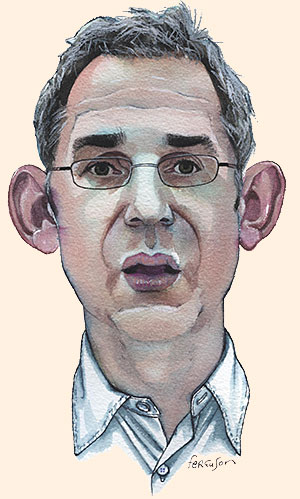

Bounding nervous energy, with a long taut face, tense features and darting hazel eyes behind black-rimmed glasses, he gestures first at the spectacular vista of the North Sea and clouds – “I want lots and lots of empty space so you can gaze up at the sky” – and then at the provisional assembling of his work “Atmosphere”.

Created in response to “the beautiful specificity of place”, this is composed of nine large vitrines, suspended at different levels from the ceiling of Turner Contemporary’s Sunley Gallery, holding 200 small celadon and grey porcelain vessels. Together they create a quiet drama of repetition and variation as each is marked by subtle distinctions in tone, texture, colour. They catch the bright, mutable light from the sea and mimic impressions of shifting horizons, evoking nature, painterly responses to it from Turner to Gerhard Richter, but also the austere language of minimalism. I think of Donald Judd’s shelves, but de Waal mentions Wallace Stevens’ “Anecdote of the Jar”, where a “gray and bare” jar “took dominion everywhere”.

“Did you ever write poetry?” he asks before confessing, “I did, of course, absolutely! Poetry has been the core, poetry is the core. It’s funny because I’m 50 this year and I’m now allowing myself to talk about poetry, to make poetry and to write poetry, and I’m loving that return.” His Margate exhibition includes for the first time a text piece: a corridor converted into a “life-size notebook” of favourite quotations, opening with JMW Turner’s “atmosphere is my style.”

“Why wouldn’t you want to bring into conversation, you know, Rilke and Turner and Ruskin and Baudelaire?” de Waal rushes on. “If you’re standing in Margate looking out of the window, all those people are looking out of the window with you. When thinking about the changing landscape of clouds, I remember Constable’s beautiful letter about lying on his back and doing ‘a great deal of skying’.” He looks around and adds, “We could just spend an hour looking at the sea!”

…

As he leads me to our picnic, de Waal, tall and skeletally thin, calls to mind a walking version of one of his own sober, elongated vessels. Ascetic yet an attentive host, he offers wine but declines himself – “I need to be up a ladder all afternoon” – in favour of mineral water. He has obsessively made pots since he was five years old; by the late 1990s he was exhibiting them in progressively more complex combinations, marrying craft to sculpture and installation. In the 21st century, public commissions such as “Signs and Wonders” (2009), in the uppermost cupola of the Victoria and Albert Museum, established him as one of Britain’s most original conceptual artists.

He became a household name, however, as a writer. His 2010 memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes, tracing the fates of his paternal grandmother’s family, the wealthy Ephrussi from Vienna who fled Nazism to Britain, through stories about a collection of Japanese netsuke, was a bestseller translated into more than 20 languages. De Waal has never felt writing and making art are separate: “I don’t really suspend one activity for the other. It sounds incredibly bogus but there is so much writing in making pots, and so much weight and shape to the writing.”

We begin with a starter of thick beetroot soup – “borscht”, de Waal jokes, “to join our different paths of Mitteleuropa together”. (My mother’s family came to Britain from Berlin in 1939.) But The Hare is, I think, more than an account of European displacement; it is about the inevitable fragmentation of history, art, lives.

“I’m working through private ideas in public,” de Waal explains, “and a lot of these are quite odd, to do with language, survival, memory. I’m going back again and again into what collecting means. Collecting is the attempt to hold memory together, which you know is not possible – memory is diasporic, it disperses. Someone who makes objects of incredible fragility and insecurity and puts them with a name into a cabinet or on a shelf 35ft in the air” – he motions towards “Atmosphere” – “is saying, it’s there, but for how long? It’s a bet. You make a pot in west Norwood and take it to Margate or Madison Avenue and the world slightly changes, people come or don’t come. That valuing of the slightness of something, I really love.”

Madison Avenue refers to his inaugural American show, last autumn, at Gagosian Gallery; its title, “Atemwende”, or Breathturn, comes from “Der Meridian” by Romanian poet and Holocaust survivor Paul Celan. New York’s reaction was ambivalent: the New York Times called de Waal “ostentatiously precious and ultimately naive” and lamented that “he has a deep training in and love for the art, craft and history of ceramics that . . . has been overtaken by the ambition to be an installation artist”.

An essay by critic Adam Gopnik, on the other hand, suggested that de Waal’s central challenge was “remaining loyal to the very British, handmade, small-scale ceramics that were his first devotion while still seeking the scale . . . of American abstraction”. “Why can’t you be in the grandest gallery on Madison Avenue and have an installation about Paul Celan and fragments?” asks de Waal. “It’s all possible! Jesus, the work has lot of rigour and thinking behind it!”

He loves “the rigour of The Well-Tempered Clavier or early Donald Judd or Mies van der Rohe – but then within that kind of rigour you can do a very relaxed and humane and open thing about having some pots, a cluster of pots. That’s the human side. The scale of things is fascinating. I’m hugely hugely hugely ambitious. I want to work in the best, most interesting spaces, be present, but I’ve got no iota of grandeur in me. I never had any expectations of ‘success’, but I had utter expectation of being able to work, do what I wanted to do.”

As we move on from the soup to what the menu calls “a hearty seaside sandwich” – salmon interleaved with chopped vine tomatoes and crunchy bitter salad, moistened with balsamic vinegar and olive oil – I ask how British is de Waal’s cultural identity? “I’m lapsed from everything. Lapsed Quaker, lapsed Anglican, new Jew, wannabe Buddhist.”

He was born into a clever, competitive clerical family, the third of four boys. His parents, who have separated, are Reverend Victor de Waal, who was Dean of Canterbury Cathedral and now, aged 85, works in a refugee centre in Islington, and Esther de Waal, a vicar’s daughter, who lives alone in Wales and continues to write books about spirituality.

“There were real complexities to growing up in public, in a clerical family you are very much on view, though one positive is that it can give you a slight fearlessness in talking to people. And robust argument is a wonderful environment for any child.” Two of his brothers are writer-activists on human rights, in Africa and the Caucasus, and one is a barrister, “so we’re all out there in the world doing things, that’s good. We’ve gone in different directions; we knew intuitively the best thing was to give each other lots of room.”

As a child, de Waal singled himself out from his literary family by working with his hands, only to become the most celebrated author of them all. “Certainly, there was a lot of self-defining about saying there are some things that can’t be brought easily into words”, he recalls. “I really did make an awful lot of pots. I was very much in flight from words, trying to close that down. I had a very strong self-image of someone who had to do that strong craft life – making things of beauty which also had utility. They weren’t very good – well, some of them were very beautiful, they were pretty well made, I was a pretty good studio potter. It was a very long apprenticeship.”

He compares it to learning to play the piano: “Any musician has been through that journey. Everyone understands it with music, and until a generation ago everyone understood it in the visual arts. If you’d talked to Cy [Twombly] in old age or Jasper Johns or Ellsworth Kelly they’d say, ‘Of course you have to learn’: it’s about developing articulacy in a medium.”

De Waal’s training began in his early teens at King’s School, Canterbury, where he was taught by potter Geoffrey Whiting, a disciple of Bernard Leach, in the 1970s considered the father of English studio pottery. Leach was heavily influenced by Japanese ceramics, and de Waal studied in Japan before reading English at Cambridge, where “I was liberated because I knew I was going to be a potter not an academic. But I read Stevens and Pound, and I did bloody well, I got my first!” It was at Cambridge that he first met Sue, whom he later married, but after graduating she worked in overseas aid, while he went to Wales where he lived reclusively making inexpensive domestic pots in earthy colours which no one wanted. (The couple, who have three children, now live in London.)

Stuck, he returned to Japan in 1991 to research a book demystifying Leach. “It’s anxiety of influence – you choose which father to kill, and in my case it was Leach. He was very self-aggrandising and I hope I managed to put that down – that slightly hectoring overseriousness, a very English adopted seriousness rather than the real, attentive unpicking of problems and ideas over time. He believed it was the world’s fault for not understanding the value of craft and the object, it wasn’t anything to do with him and the objects he made, the world owed makers a living and seriousness. That’s such shit. There’s a hangover of that in the craft world, real anger that the world doesn’t understand. My response? Well, I don’t know how to begin . . . ”

At this point he laughs at his earnestness, and suggests that my next sentence should be “He spluttered into his cheese.” We now notice that the vacherin is beginning to run in the sun, and we alternate slivers of the creamy French and sharp English cheeses while de Waal continues, “Manifestly, the connections between things, ideas and people are there for the making. Begin again! That crossness is something I put down and walked away from. Leach just came off my back. Well, it’s easy to say it in this beautiful space looking out at the sea.”

With Leach deposed, “the making got more liberated”, de Waal began working in porcelain, opening up his more lyrical, philosophical strain, and responding to art history – his allusions range from the purity and elegance of Chinese porcelain, to the English cathedral architecture with which he grew up, to the simplicity of Bauhaus.

We abandon the cheese – “you must take these back for your children, the vacherin has to be eaten today” de Waal insists, wrapping it up for me – and sample the dessert, a chocolate mousse, infused with orange, deliciously rich but too filling to finish. Then we leave our corner table to survey the polishing of “Bauspiel”, a group of abstract forms on a plinth intended as “a cheerful conversation with Bauhaus building blocks, but in [Turner Contemporary’s] beautiful David Chipperfield series of volumes with sea and light, it was too good a chance not to have a cityscape.”

Such works ask, how much meaning can an object hold? Why do objects matter? “That’s a bit like asking why does music matter,” de Waal answers, slowly. “Music is the first bit of pacing of the world for a child. Objects are as core as music, they are less talked of, we fall away from them culturally quite quickly, but you can reclaim objects as a central part of being a human being. It’s not that they define you but the objects that have been made through history have always been made with something extra in them – that extra pulse of attention, pleasure.”

The Hare distils that care and delight in prose but in writing it de Waal also discovered “how real stories are fissured, they break up and become dangerous. I thought I’d got it covered and knew the emotional range and shape of the story, that it was complicated but safe, but it got more complicated, painful, in danger of changing me. My English friends think I grew up with Goethe and Linzertorte but ask the child of any refugee and they say the same – for your emotional safety your parents tell you nothing at all.”

The gaps between the sayable and the unsayable, order and fragility, seem to me leitmotifs connecting de Waal’s literary and visual work. “The poets that you care about are always fiercely finding these places where they stop and the unsaid happens, and that’s so present in sculpture,” de Waal suggests. “It can be as delicate as the way in which a sculpture meets the floor or how light changes around it. I’m completely completely completely optimistic. I work with porcelain, and the world is full of shards, broken things, and I know that my work will end up as shards and that’s the cause of so much happiness and optimism, that you’re part of something, going on and on.”

‘Edmund de Waal: Atmosphere’, Turner Contemporary, Margate, to February 8 2015, turnercontemporary.org

Jackie Wullschlager is the FT’s chief visual arts critic; read her Titian review

——————————————-

Beamish & McGlue

461 Norwood Road

London SE27 9DQ

Beetroot, horseradish and ginger soup x 2 £5.90

Flute sourdough loaf £1.65

Salmon sandwiches with roasted vine tomatoes and bitter leaves x 2 £9.90

Chocolate mousse x 2 £7.00

Cheese plate £7.40

Packet of crisps £2.25

Bottle Belu water £2.00

Bottle Saumur-Champigny £13.90

Total £50.00

——————————————-

Letter in response to this article:

Exquisite pleasure of the perfect pot / From Dr Anne-Carole Chamier

Comments