British design phenomenon Barber Osgerby: ‘Our job is to give a dopamine hit’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ask British industrial designers Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby about the defining moments of their career and Barber will probably recount the time he went into a shop, only to find a £2 commemorative coin the pair had designed for the 150th anniversary of the London Underground in his change. There was also the “pretty scary moment in 2014” when they suspended a revolving metal, mirrored installation the length of a Boeing 737-700 for BMW in London’s V&A Museum. “On the opening night there were 400 people from the design community standing beneath it sipping champagne. I remember looking at it and thinking, ‘If this goes down now...’” Barber says. “The piece highlighted the Raphael Cartoons in the Raphael Gallery, which are all owned by the Queen. Basically, it was the equivalent of putting her paintings into a NutriBullet.”

Or there’s the experience of designing the 2012 Olympic Torch, which was carried across the country for 70 days leading up to the opening ceremony. “It was such an incredible feeling – only we couldn’t look as Steve Redgrave ran into the stadium,” laughs Osgerby. “If it had gone out, we’d have probably ended up working in Woolies.”

It’s these kinds of projects – experimental, exhilarating and nerve-racking – that keep the creative blood pumping for Barber and Osgerby. They may be known for a design approach that instils simplicity into form and function, but they like being out of their comfort zone, working at what they call the “scarier side of challenging” and frequently venturing into unfamiliar design.

This is why their work is so diverse – there has been furniture for design brands such as Vitra and Cappellini and lighting for Hermès and Louis Vuitton. They have turned their hand to fabrics, tiles and showers, collaborated with Coca-Cola, Sony and Levi’s and overseen large-scale architectural projects. “We don’t see the boundaries and we’ve never conformed to being put in a particular box,” Osgerby says. “I think that’s what’s kept us really energised and creative as a studio.”

It’s this resistance to being straitjacketed by expectation that brought the pair together. They met as students at the Royal College of Art in 1992, but found the architecture and interiors course they had signed up for too lacklustre for two eager and ambitious designers, and vented their frustrations by joining forces to get their ideas out of the sketch book and into the world. Luck brought them a commission to design a west London restaurant (they later worked on Damien Hirst’s restaurant Pharmacy, in Notting Hill). That early commission produced a design for their Loop table that sat on a shelf until they convinced Chris McCourt, the owner of Isokon Plus (the furniture company that appointed Walter Gropius as controller of design in 1934, who was succeeded by protégé Marcel Breuer), to put it into the range: it was the first to be added to the collection for 33 years. Loop, which marks its 25th anniversary this year, was a breakthrough piece, now held in the permanent collections of both the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

The pair are celebrating this milestone at their studio in London’s Shoreditch, an airy whitewashed space punctured by colourful design objects and vibrant sketches pinned to the walls. They employ around 10 people at this hub and there are two further arms of the business, Universal Design Studio (their architecture and interior-design practice, which fitted out the east London outpost of the Ace Hotel) and MAP, a “strategy-led creative consultancy”. Both of these businesses are now housed in Clerkenwell, having been acquired in 2018 by AKQA, which bought a majority stake in them for an undisclosed sum. As one of the biggest digital and design agencies in the world, AKQA employs 2,200 people globally and according to its annual report in 2019 had a turnover of £31m in the UK.

The pair fit in well in this part of town. Barber sports dark-framed glasses under short dark hair, while Osgerby, slightly tanned, has a sweep of brown hair that he constantly scrapes back with his fingers. Both essay a kind of laidback nonchalance, in casual shirts and jeans rolled over trainers and boots, as they take me through the list of projects they are launching this year, which kicked off with the launch in February of a floor-standing version of their Bellhop lamp for Flos (you might have seen the Supreme tabletop version). There’s one in a corner of their studio, its tall, brightly coloured profile designed to be as visually engaging when it’s not in use as when it is illuminated.

Next to their worktable is their On & On chair, part of a sustainable collection for Emeco, which went on sale in March. “Lots of products are now made from recycled plastic but they get downgraded into insulation or put on roads because you can’t make more furniture from them,” Barber says of the project’s eco ethos. “But Emeco has been working on plastic that can be endlessly recycled. So when our chairs reach the end of their life, they can be remade into more of the same thing. They’ve closed the loop in the cycle.”

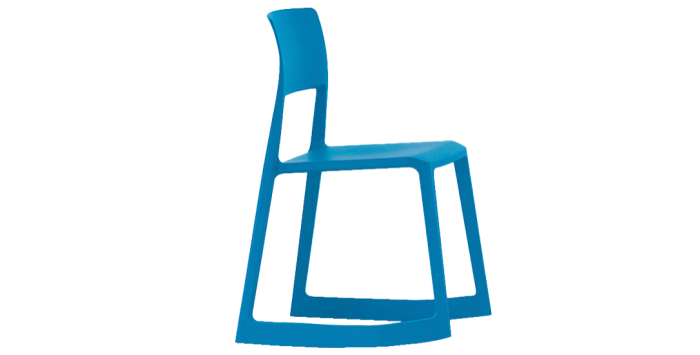

Another chair – a special 2020 edition of their stackable Tip Ton chair for Vitra from 2011 – is revised in 100 per cent recyclable polypropylene. There are sketches too of their new Axor One shower, which will be unveiled this month: “It has precise temperature control but with the very simple functionality of a tap.” And in one corner is a stack of rainbow-coloured Rimowa suitcases – they are producing new colours for the luggage brand as part an ongoing collaboration, as well as aluminium products. Looking forward, they’re excited for us to see their limited-edition furniture (a chance to “experiment and play around”) at an upcoming Galerie Kreo show in Paris, which follows a similar showcase of their work by the gallery in 2018.

“I guess you could say we’re restless,” says Osgerby of the sheer breadth of their work. “There’s something in us that is always trying to find a problem to fix. The most terrifying thought for me is to know that tomorrow will be pretty much like today.” He admits that on some subconscious level, they are trying to recreate that charged creative atmosphere and cross-pollination they found at the RCA (the side of college life they did enjoy). “You could walk into one room and sit at somebody’s table cutting fabric or soldering a circuit board,” he says. Barber agrees. “I think it was pretty marginal that we ended up doing this. I could have easily done photography or sculpture,” he says. “I suppose being a designer felt right at that moment and we pursued it.”

Pursuing this career as a duo has had its benefits. “Working for others felt like a trap, even though I’m sure there were things we could have learnt. But as we started out as students, we had nothing to lose,” Osgerby says. “People say, ‘Weren’t you brave for setting up on your own?’ but actually we weren’t brave. It was an experiment that happened to work out for us.” While they’ve gone with the flow, embracing opportunities that have come their way, they’re selective when collaborating. “The most important thing for us now is to design things that have some kind of meaning and offer a new use – and certainly with that use there should be a small ecological footprint,” Osgerby says.

Barber nods in agreement. “You want to design something that people won’t get tired of. It should be with them for the rest of their lives – and ultimately, the best sustainable story is a piece made to last a lifetime, if not two or three lifetimes,” he says. “Sustainability has been viewed as a novelty in the industry but this is all going to change. People know they don’t need to consume; there’s been a switch to vintage, so I see fewer launches in the future and a new response. For me, knowing you’ve got a good product is when you realise that it’s just as simple as it could get.” The ability to subtract without taking away has become the designers’ calling card, but it’s also an approach that comes with challenges. “The problem with really simple projects is that they’re the toughest thing to realise without rinsing the soul out of an object. There’s simplicity and there’s minimalism, and they’re two very different things,” says Osgerby. Barber stresses the point: “An object needs to have a personality to live in a space. Our job is to somehow give a dopamine hit through usage. We want to give people joy daily, whether it’s a spoon or a sofa – they are using it, loving it and can’t think of replacing it.”

All their designs begin as sketches. “In our Phaidon book [published 2017] there’s a photograph of a sketch we did of Tip Ton from a hotel bar in New York, which was genuinely the breakthrough moment,” says Barber. These design sessions have often been lubricated with a drink or two, admits Osgerby with a grin. “In the early days we’d head to Ed’s family house on Holy Island to design. We’d get the beers in and order food and we would sit there and just sketch,” he says. “At the end of the night there’d be acres of sketches going down the corridor of the house. Of course, we’d wake up worse for wear and there’d be about one per cent in there that was usable.”

There is a kind of understanding between the two that reveals their long friendship. They are considerate of each other, allowing the other to speak before they offer up an idea. “The funny thing is that we both grew up in families as one of three boys, so you grow up knowing how to have that kind of interaction,” Barber says. They find strength as a partnership to deal with the ups and downs of the business. “I can’t really imagine doing this on my own because you need a sounding board and someone you trust to get a really honest opinion,” Barber says. It’s also kept their feet on the ground. “You can’t be a prima donna,” agrees Osgerby. “When you’ve known someone since you were 21 and you’ve worked with them forever, they are going to call you out.”

Do they ever argue? “Rarely,” says Barber, “but the weird thing is we’ve become more opposite in our views as we’ve become older. There’s probably more conflict in the design process but it doesn’t end in a bust-up, it just means that there’s more to talk about.”

They find some of what they do crazy. “There are joyous moments in the process and there’s a lot of pain but usually it’s quite amazing. Take our Bodleian chair for the Bodleian Library. I mean, the last chair commissioned for it has been there for 100 years, and the one before that for almost 300 years. It’s going to outlive us and carry on,” Barber says. “We should have scribbled our names on it,” Osgerby concludes. “Ed and Jay woz here.”

The B&O story

1996

Loop Table, Isokon Plus

When the Loop Table went into production in 1996 it was the first new design to be manufactured and sold by Isokon Plus since Ernest Race’s redesign of the Penguin Donkey bookcase in 1963.

2011

Tip Ton Chair, Vitra

Angled so that it tilts when the sitter shifts forward, the chair straightens the pelvis and spine. It weighs just 4.5kg, is stackable and also 100 per cent recyclable.

2012

Olympic Torch

Facilitating grip, the perforated surface of 8,000 laser-cut circles symbolised the 8,000 people who would carry it leading up to the opening ceremony. It is held in the collections of the V&A, the Design Museum in London and the Olympic Museum in Lausanne, Switzerland.

£2 coin, The Royal Mint

Commemorating the 150th anniversary of the London Underground, the design depicts a 1967 Victoria Line train emerging from a tunnel. It uses the New Johnston typeface

Tobi-Ishi table, B&B Italia

Inspired by large ornamental stepping stones found in Japanese gardens, which represent balance and harmony, the legs are replaced by trapezoidal supports.

Bell lamp, Louis Vuitton

Part of Louis Vuitton’s Objets Nomades Collection, this is a hand-blown “bell” of frosted Murano glass, surrounding an LED light. The leather strap facilitates carriage but also gives it its distinctive design. It is held in the permanent collection of the Design Museum, Helsinki.

2014

BMW Double Space, V&A

Double Space was an immersive experience – two massive mirrored panels suspended from the barrel-vaulted roof of the Raphael Gallery at London’s V&A.

2018

Soft Work, Vitra

Soft Work developed as a response to radical shifts in working habits where advances in communications technology mean that people can work anywhere.

2019

On & On chair, Emeco

A durable chair with a round seat, the On & On (unveiled in 2019 but now available to buy) is made from a plastic that can be recycled into new chairs at the end of its life.

2020

Bellhop Supreme, Flos

A limited edition, this portable LED tabletop lamp with four dim settings is sold exclusively by Supreme. It is wireless and USB-chargeable, with a battery life of 24 hours.

Comments