Artist Mit Jai Inn: ‘My work is a process, a living condition, not painting’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Visitors to Dreamday, a solo exhibition by Thai artist Mit Jai Inn, can tread across a carpet of silvery, pigment-flecked paint. Other gallery-goers touch the multicoloured dots of the freestanding canvas scroll nearby or trace their fingers through the thick ribbons that form an eight-metre tunnel in the middle of the room. An atmosphere of childlike free play, not formality, complements the trippy, hyper-sweet surfaces of these minimal forms — the interactive aspect is clearly all-important. “Art for me is not just something in the corner. It should be close to you,” explains Jai Inn at Bangkok’s Jim Thompson Art Center.

Born and raised in northern Thailand, the artist is known domestically for socially engaged art projects. He co-founded Chiang Mai Social Installation, an artist-run festival series that took place in temples and other public spaces across Thailand’s second-largest city in the 1990s. In 2015, a year after the country’s last coup d’état, he launched Cartel Artspace, a non-profit Bangkok gallery where artists often broach the country’s pseudo-democratic climate. Informed by cosmopolitan influences, from Theravada Buddhism to Joseph Beuys, these and other initiatives fly in the face of commercial developments in Thailand, such as state-sanctioned biennales.

Most are also calculated reactions against centralised forms of power. In 2022, for example, Cartel Artspace staged a strident exhibition of ephemera from the country’s recent student-led protest movement, just as its leaders were slapped with draconian sedition, computer crimes and lèse-majesté charges.

For most of his 30-year career, Jai Inn’s art-making — a seemingly placid form of “expanded painting” centring around bold manipulations of canvases, paint and people — has also existed outside the system. “I’ve never really earned a living my whole life,” he says. But that is changing, albeit on his own terms. Gallery representation and biennale appearances over the past decade have helped his international profile to grow, while the works produced in his mountain studio in rural Chiang Mai have taken on an immersive, often epic scale: towering tapestry-like hangings; pools of linseed oil and viscous paint; a 100-metre wall of canvas streamers fluttering in a flower field.

A practising, if irreverent, Buddhist, 62-year old Jai Inn views his labour-intensive exploration of the materiality of colour at the heart of this new chapter, or rebirth, as a form of release. “The focal point is meditation,” he says, referring to how he smooths and scrapes blends of recycled oil paint, gypsum powder, pigments and reflective minerals using palette knives, hands and fingers. “My work is a process, a living condition, not painting.”

The unspoken art-historical references to action painting and colour-field painting, abstraction and postmodernism that characterise Jai Inn’s psychedelic forms reflect his years in Europe, where he arrived in the late 1980s after studying at Silpakorn University, Bangkok’s pre-eminent — yet conservative — fine art school. “At that time, I was disillusioned with everything. I looked down on every artist and type of art,” he says. But his years in Berlin and Vienna proved edifying. While doing his masters at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, he worked as a studio assistant for the Austrian artist Franz West and became interested in radical notions of art authorship and ownership: essentially, he started giving his art away.

Jai Inn’s belief that the social connections and sensory energy circulating around art objects trump orthodox considerations, such as scarcity, provenance or price, intensified when he returned to Thailand in 1992. One memorable “social installation”, as he calls them, was a midnight walking tour in Chiang Mai in 1995; participants tied to a jute rope carried rocks through city streets. Another was Dreamday’s early-December opening, where 74 objects in cheerful pastel colours (papier-mâché stones, otherworldly-looking metal lamps) were gifted to visitors in an adjoining gallery. In exchange, they consented to open their homes up to the public. “Bangkok Apartments” is a new, post-pandemic iteration of his career-shaping 1991 thesis project, “Vienna Apartments”. “Some say you cannot give work away, because you have a contract,” he says mischievously. “But I deal in my own way. In 2023 I plan to give away another 1,000 works!”

Despite ancestral ties to western art canons, some of the works accompanying Jai Inn’s latest social intervention are loosely inspired by northern Thai culture. Draped down the left side of the art centre’s facade, “People’s Flag” (2022) — a seven-metre-long canvas with bands of bright colour — speaks to memories of his mother, a member of the ethnic Yong tribe, wearing the paa sin, a multicoloured, sarong-like skirt. “I’ve turned the colours of paa sin’s woven cotton into a national flag . . . Not a macho flag, like Russia’s or Thailand’s, but something more ladylike. A new flag for the people.”

The central piece “Dream Tunnel” (2021) obliquely references the Thai royal court’s recruitment of silversmiths from another northern tribe, the Tai Khun. The exterior of its double-sided sliced canvases, which dangle neatly from the rafters like yarn from a weaver’s loom, is wreathed in silvery metal paint. Its effect is more contemplative than provocative, but Jai Inn stresses that it alludes to the erasure of cultural identities and craft traditions. “Our tribes have been hijacked,” he says, leaning against the courtyard wall at Jim Thompson Art Center, puffing on his third cigarette.

The titles of his recent exhibitions more openly signpost his belligerent views on the direction of society in his homeland, where colours are freighted with cultural symbolism. Held at galleries in Taipei, Hong Kong and Manila, The King and I, Royal Marketplace and Junta Monochromes each framed Jai Inn’s candy-coloured environments — which he likens to “stages or set design” — as sarcastic metaphors for Thailand’s societal spectacles, illusions and anxieties. Where does the innocuous-sounding Dreamday, a new iteration of a 2021 solo exhibition at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery, fit in his hall of mirrors? “It’s about the day of them,” he snaps, clearly referencing the country’s rulers, something his maltreated canvases never do.

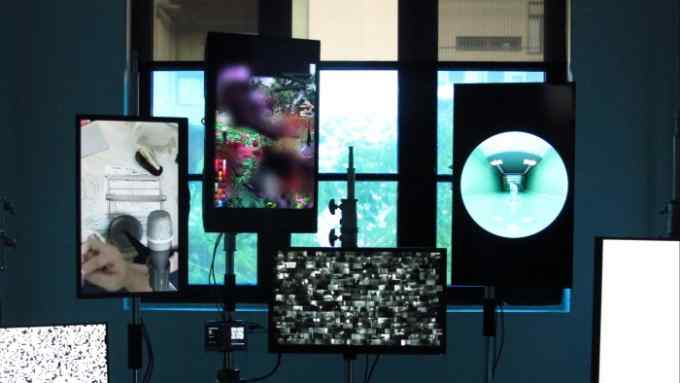

Despite these ominous undercurrents, the show has a liberating and, yes, dreamy quality. Breaking what Gridthiya Gaweewong, artistic director of the Jim Thompson Art Center, calls the “perspective-monopoly of the wall”, Jai Inn’s interactive, polychromatic artworks offer a form of escape and empowerment — not a grim reality-check — while “Bangkok Apartments” is designed to bring strangers together.

Like the adventures preceding it, Dreamday is an exhibition informed by his concept of the sangha, or Buddhist community, and his belief that art should point towards and shape a more equal society. “In my eyes, the duty of the viewer is not to view art,” he says, “but to give it function, to make it practical in daily life. Art for me is about the utopian dream of everyday reality.”

To February 2023, jimthompsonartcenter.org

Comments