A Gio Ponti pilgrimage in Italy

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

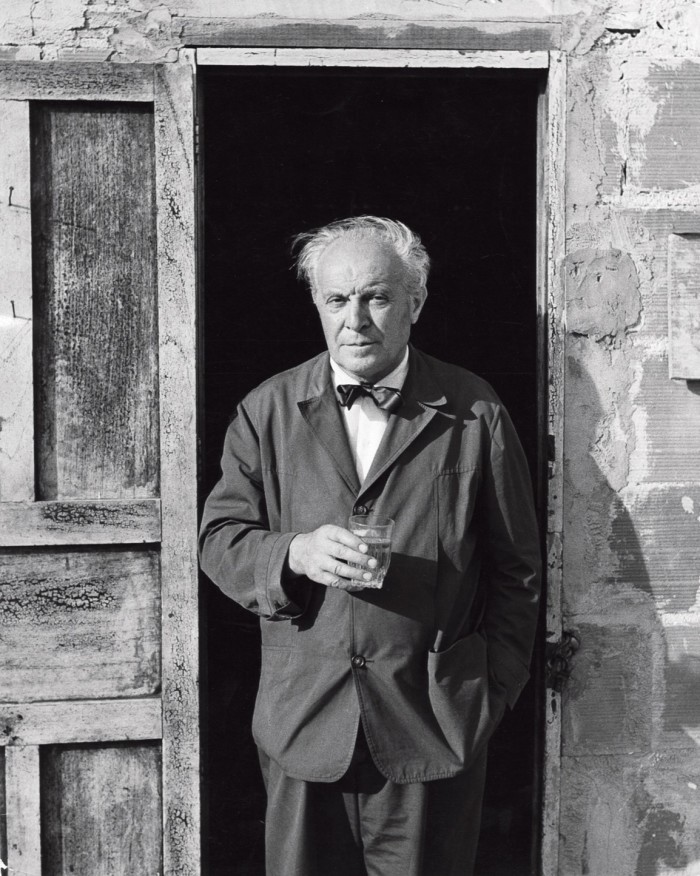

Architect, designer, artist and writer: Gio Ponti was a polymathic powerhouse whose mind-blowing output spanned everything from spoons to skyscrapers. His pioneering take earned him the mantle “the father of modern Italian design”. Ponti’s buildings can be found across the world, but left an indelible imprint on Italy – in particular on his hometown of Milan, where numerous landmarks still stand today, offering a glimpse into his life and work.

Ponti lived in several houses in Milan, but it is his final home, in an apartment block he designed on Via Dezza, that makes the best starting point for a Ponti peregrination – not least because it also housed his ground-floor model studio, which today is run as an archive by his grandson Salvatore Licitra. Some of Licitra’s fondest childhood memories are of gatherings at the family apartment on the eighth floor, where Ponti resided from 1957 until his death aged 87 in 1979. “It was a magical space full of curious and attractive objects: ornaments, sculptures and paintings,” he recalls. “Our grandparents were always happy and had fun joking around with us children.”

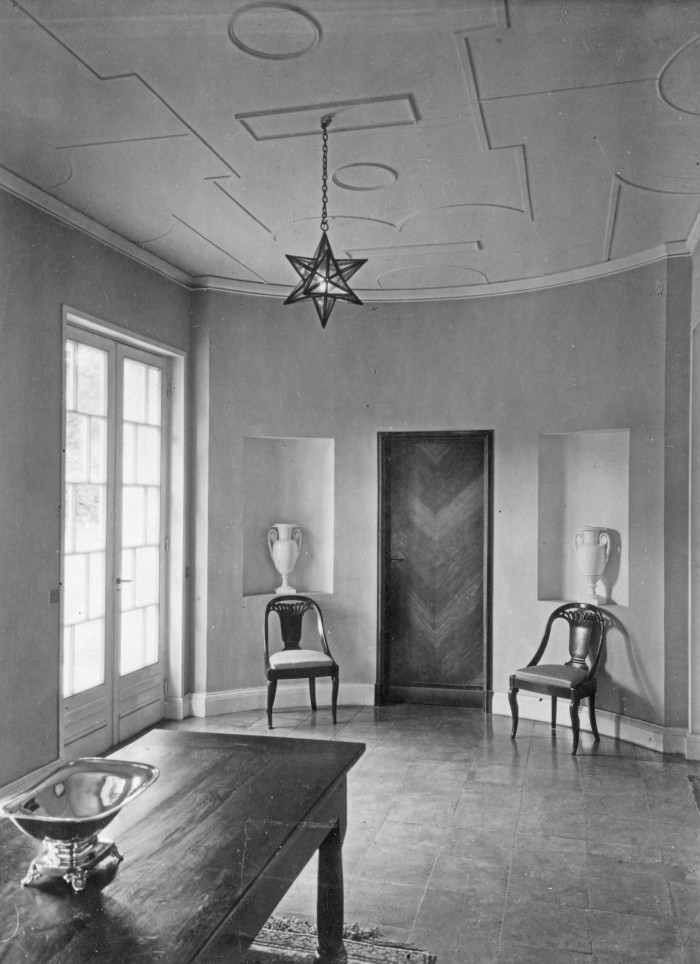

Ponti poured all his ideas about design and architecture into Via Dezza, a vision of modern living, constructed as stacked segments, housing customisable, open-plan apartments with “movable walls” to close off spaces. The homes also showcased Ponti’s “furnished windows” (a distinct feature of the façade underlined by colour, which inside became a “fourth wall” accessorised with drawers, cantilevered tops and shelving). In his own art-peppered apartment, the chairs and beds were identical throughout, and the floor and ceiling clad with handmade coloured tiles.

Licitra remembers how bright and welcoming it was. “The handmade striped ceramic floor united all the spaces as if it were a single stage on which to represent domestic life. Walkable, open and full of objects, it was so exciting,” he says. “It reflected my grandfather’s intense creativity but also proposed a simple life.”

Licitra admits that his grandfather, a workaholic who could be “inattentive” at times, made no distinction between work and home, where visitors constantly came and went. “Work was conceived as an expression of his personality, and family life was totally open to his business contacts.” But his enduring impression of his grandfather remains one of a man who was an eternal optimist. “His main working tool was enthusiasm, which he communicated to collaborators and clients who inexorably became friends and members of a sort of extended family.”

Licitra did not follow in his grandfather’s footsteps as an architect, instead studying philosophy before taking up photography. But fate decreed that he would become the custodian of Ponti’s legacy later in life – at Via Dezza. “My mother, Lisa Ponti, had kept both the photographic archive from his studio (a collection of images of Ponti’s work from the 1920s to the 1970s) and his correspondence for years, in order to work on the book Gio Ponti: The Complete Work 1923-1978 [published in 1990], which was entrusted to me in 1996, when I set up the archive.”

Imagery aside, the collection includes more than 100,000 letters written and received by Ponti, revealing relationships with fellow architects, artists, politicians and industrialists. Licitra, meanwhile, has continued to add to the trove with new photos and documentation, creating a historical resource available to researchers (by appointment) and loaned to museums and exhibitions. “The goal is to represent Ponti’s work against the background of the cultural history of the 1900s,” he says, as he unpacks boxes returned from the blockbuster Ponti exhibition at Rome’s MAXXI in 2019. He points to his collaboration with the furniture company Molteni&C, which has reissued pieces from some of Ponti’s most important houses using original drawings from the archives.

Why does he think his grandfather’s designs, so instrumental to the mid-20th-century Made in Italy movement, still resonate today? “Definitely luck: Ponti jokingly claimed to be ‘persecuted by luck’ for being able to live, work and exercise his creativity at a time of phenomenal technological innovation and social change,” Licitra says, adding that curiosity also played its part. “He loved and studied Italian cultural heritage, the arts and craftsmanship with a lively curiosity, not motivated by nostalgia but rather reworking these elements like an artist and illuminating them with a contemporary light.” Communication was the thread that bound it all together. “His work was constructed to communicate a message. It lived in the gaze of the public.”

I ask him which landmarks he would recommend to visitors making the pilgrimage to Milan. “It’s a very long list,” he jokes, but reels off a roll call of names. “Certainly the Pirelli skyscraper and the two buildings designed for Montecatini from 1936 and 1951. Then there’s the house in Via Randaccio from 1925, Ponti’s first house; Casa Rasini from 1933; an example of what Ponti called ‘typical houses’ in Via De Togni; and the church of San Francesco.”

Via Randaccio, the first of four family villas Ponti designed and lived in, is certainly worthy of an Insta snapshot – just don’t use a long lens, as it’s also Licitra’s home – and lifts a curtain on Ponti’s early style influences. “It’s an elegant tribute to Palladio’s architecture. All the pieces by Ponti are somehow special,” he says of the pale‑green villa replete with neoclassical details. Ponti did not begin life as a modernist and his aesthetic continually blurred into the eclectic.

By the time the four-storey building was completed in 1925, Ponti, having married Giulia Vimercati (in 1921), was part of Italian high society and working in partnership with Mino Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia at their architectural firm. A chance meeting with the owners of the Richard Ginori ceramic factory landed him the role of creative director – and solidified what became a lifelong love of ceramics. His work here, also influenced by neoclassicism, flew in the face of the modernist “functionalists” of the time, earning critical acclaim.

A compulsive collaborator, he produced projects thick and fast: he conceived cutlery and candlesticks for silversmiths Christofle (and designed the famed L’Ange Volant house for its director Tony Bouilhet on the outskirts of Paris in 1926), and chandeliers for Murano glassmaker Venini. His furniture designs were diverse: luxe creations for Il Labirinto group (which he co-founded in 1927) were countered by affordable pieces for the department store La Rinascente. As a flag-flyer for democratic design, he showed examples at the Venice Biennale and Monza Triennale, and tirelessly promoted the work of others, particularly new talent. Ponti not only used his social connections to this end, but in countless articles (he somehow found the time to launch the design and architecture magazine Domus in 1928 and the art title Lo Stile in 1941) documented fresh thinking as an important aspect of Italian culture. A mouthpiece for modern living, he aided Italy’s transition into the design hub of the world.

Casa Rasini – the red-brick tower, which was the last Ponti designed with his friend Emilio Lancia in 1932 – hints at a gear change towards full-throttle modernism, as do his “typical houses” or Domuses, built between 1931 and 1936: simple externally but new and modern inside. FontanaArte, the lighting and furniture company he founded with designer Pietro Chiesa, provided other creative outlets (iconic designs ensued, such as his Bilia and Pirellone lamps and the Tavolino 1932 table, which are still in production today).

Ponti’s work took a decidedly modernist turn when he established his own architectural firm in 1933, bringing in the engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncin as partners. The Montecatini office building on Via della Moscova – its façade punctured by grid-like rows of windows – offers a glimpse of their vision.

By the time Ponti conceived his most famous building in 1955 – the Pirelli Tower – he was at the zenith of an incredible career. An early example of a skyscraper, overlooking Piazza Duca d’Aosta, his glinting edifice – some 127m high and wafer-thin when viewed from the side due to its bevelled edges – was Italy’s tallest building until 1961. “She is so beautiful that I’d love to marry her,” Ponti declared when Pirellone (“Big Pirelli”), as she became known, was completed.

These were Ponti’s golden years, symbolised by arguably his most iconic design, the Superleggera chair for Cassina (1957) – a new take on a traditional ladder chair, where the superfluous was subtracted to produce the lightest design. He called it his “chair-chair devoid of adjectives”.

Of course, his work rarely fitted neatly into boxes, and for much of his career he explored a love of decoration with the artist Piero Fornasetti. Their decades-long partnership intensified in the 1950s – Ponti’s designs became canvases for Fornasetti’s graphic patterns and motifs as together they aimed to bring art into more people’s homes.

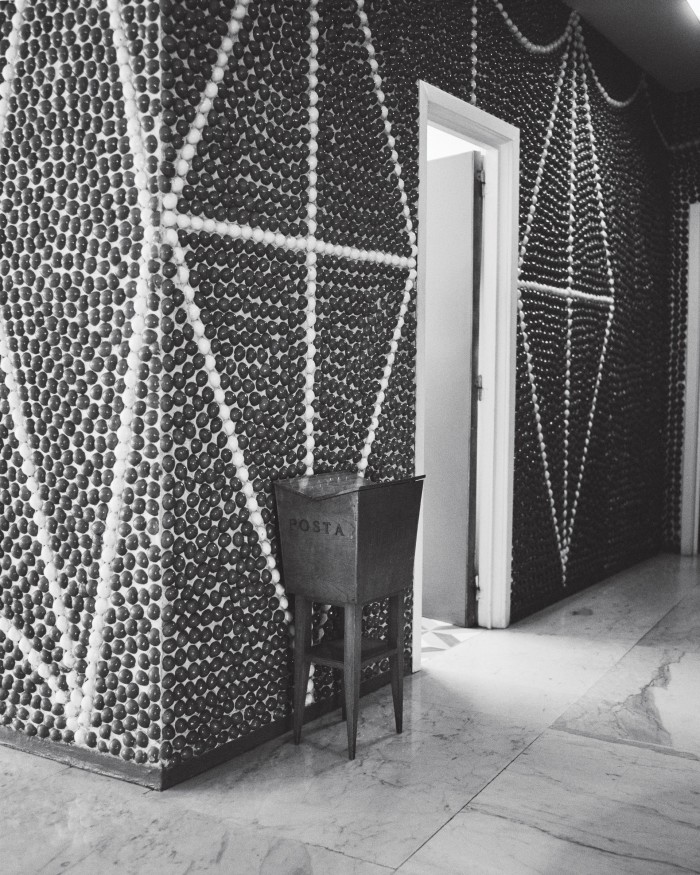

Obviously today, only those fortunate enough to own or rent a home in one of Ponti’s buildings can immerse themselves in his vision. But the rest of us can experience it – even if only for a short spell – by leaving Milan for the Parco dei Principi in Sorrento. Licitra believes Ponti would be immensely flattered that his vision for the five-star hotel (which he designed in 1960) remains largely intact. “He worked hard on hotels and wrote texts on what they should be like; he wanted them to be desirable places.” For Licitra, the hotel represents “a new brisk and modern use of an ancient tradition”, given that Ponti was commissioned to build atop an existing Gothic dacha on the Bay of Naples. He created a buzz with his modernist extension, which appeared to hover over the clifftops, and lavished attention on the interior finishes, using pebbles and ceramics.

“Ponti wrote that a hotel had to be visually exciting. Colour was a fundamental tool of his work, and here the colour of the sea was the protagonist,” Licitra says of the interior’s striking blue-and-white scheme. “He played a game with ceramic tiles, taking advantage of the handicraft tradition of nearby Vietri, while creating 33 tile designs that could combine to generate different decorative motifs. This gave every hotel room a different floor design, but also the very precise geometry combined beautifully with the imprecision of Vietri’s hand-painted ceramics.”

A 243km detour to Taranto brings the Ponti story full circle to 1970, when he was approaching 80. Here stands the Concattedrale Gran Madre di Dio, a skeleton-like cathedral perforated by slits and apertures, including what Ponti called a “door to the sky”, that celebrates its 50th anniversary on Sunday 6 December. It is an exceptional work of art in a drab port city. But then, that’s the point. “Ponti always said he was an artist in love with architecture,” Licitra concludes.

Gio Ponti Archives, gioponti.org. Molteni&C, molteni.it.

GIO BRIO: A TIMELINE OF ICONIC DESIGN

1925

Ponti’s family home, 9 Via Randaccio, Milan

The first of four villas designed and lived in by Ponti, and reflecting his early influences in its neoclassical detailing.

1926

Villa Bouilhet “L’Ange Volant”, Garches, near Paris

Ponti became friends with Tony Bouilhet, owner of the Christofle silver factory, who asked him to design a villa. According to Licitra, the project was to be “an elegant competition with French culture”, a distinct “casa all’Italiana”.

1928-79

Founder and editor, Domus

Ponti edited the design and architecture magazine until his death, only taking a hiatus between 1941 and 1948, when he launched a second title, Lo Stile, an art magazine that also promoted craft.

1933-36

Casa Rasini, Milan

This was to be Ponti’s last building designed with fellow architect Emilio Lancia. In 1933, he established his own architectural firm and took a decidedly modernist approach.

1949-51

D.151.4 armchair

The D.151.4 was conceived (with slight variants) for the interiors of several ocean liners designed by Ponti, and has now been reissued by Italian furniture brand Molteni&C (£3,792).

1952-55

D.655.2 unit

Produced by Molteni&C using original drawings kept in the Gio Ponti Archives, the D.655.2 features hand-painted white drawer fronts with applied handles in elm, Italian walnut, mahogany and rosewood (£5,915).

1953

D.153.1 armchair

The D.153.1 armchair was part of the furniture designed for Ponti’s private Via Dezza house. This re-edition, produced by Molteni&C, is based on the original drawings from the Ponti Archives (£4,192).

1953-57

D.154.2 armchair

The D.154.2 armchair was originally designed for Ponti’s Villa Planchart in Caracas, and has been re-issued by Molteni&C (£4,130).

1955-60

Pirelli Tower, Milan

Italy’s tallest building at the time, this early skyscraper, designed for the Pirelli tyre company, is Ponti’s most famous building. It was radical, with its diamond footprint, tapering silhouette and modern, airy interiors.

1957

Apartment building, Via Dezza, Milan

This building showcased all of Ponti’s architectural and design ideas, and was his final home – he lived on the eighth floor until his death in 1979. It is now the site of the Gio Ponti Archives, run by Ponti’s grandson Salvatore Licitra.

1960-62

Hotel Parco dei Principi, Sorrento

The Ponti-designed hotel still welcomes guests to this day. It is a showcase for his love of tiles and colour – its blue-and-white scheme inspired by the intense hue of the sea and sky that frames the Amalfi coast.

1970

Concattedrale Gran Madre di Dio, Taranto

A religious man, Ponti designed several churches, but this cathedral stands out for its sail-like structure referencing the city’s maritime history, and a façade of slits and apertures that gives it a weightlessness.

Comments