Behind the scenes at the making of a Bordeaux classic

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

At this time of year, the vineyards of Bordeaux are at their most desolate, the vines standing frozen and naked in the earth like so many bundles of sticks. But down in the cellars, the new vintage is starting to take shape, as the freshly fermented wine embarks on its miraculous transformation in the oak barrels.

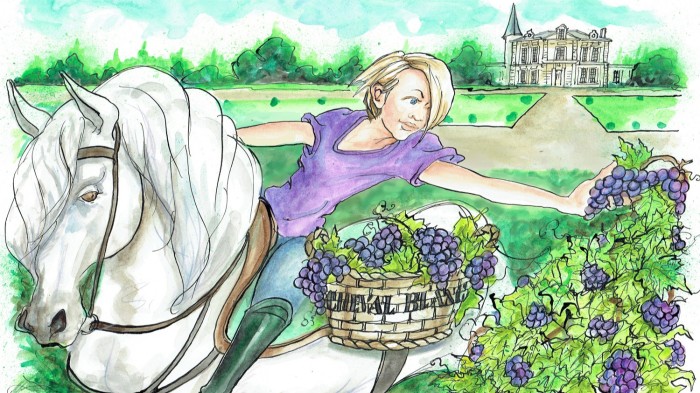

I’ve been thinking about that wine a lot lately, because just a drop or two of it might have something to do with me. Last September I had the pleasure of taking part in the harvest at Château Cheval Blanc.

This fairytale estate in St Emilion doesn’t welcome visitors very often. But for one day in every harvest, they invite 60 guests to seize a pair of secateurs and take part in the vendange. As I quickly discovered, grape-picking is an onerous task. It’s the repetition that does it. You’re doing the same little movements over and over again. Squat, clip, chuck, shuffle, squat, clip, chuck, shuffle, up and down the rows. Then, just when your quads are about to give out, you have to heave your grape-filled bucket up and over your head and empty it into a pannier on someone’s back. It makes Pilates look like a walk in the park. We only did an hour of picking in all – a pathetic amount. But by the time we finished we were all pouring with sweat.

Even so, I loved it: the click click click of secateurs going up and down the rows, the gossipy chatter between the vines as the pros sped along behind us, clearing up our mistakes; the hunt for each pendulous bunch of purple grapes, veiled in a powdery bloom so they are almost blue; the snip, and then the satisfying weight of the ripe fruit dropping into your hand; the juice, the stickiness, even the mud.

Cheval Blanc is famous for making red wines that are dominated by Cabernet Franc – unusual for an estate on the Right Bank, where most blends are majority Merlot (on Bordeaux’s Left Bank, by contrast, the dominant grape is Cabernet Sauvignon). Cabernet Franc has a lot in common with Cabernet Sauvignon – it’s got that same cassis fruit, but with a more green, leafy character like blackcurrant bush. “It gives the wine a lot of points, like pixels almost, which means that over time the wine retains more definition,” says Cheval Blanc’s boss, Pierre Lurton.

Over lunch in the beautiful gardens, we slaked our thirst with Cheval Blanc beer (brewed for pickers only, I’m afraid) and vast jeroboams of Cheval Blanc 1989 (£4,750 for a 12-bottle case from biwine.com) – “a mythic vintage”, says Lurton. Despite its age, the wine had a cool silkiness – it smelled of cedar, green peppers and lilies about to go over the top. On the palate, black cherry and cassis narrowed to a fine point of bitter black chocolate. It was magnificent and, as Lurton said, still sharp in focus. Let’s hope the 2019 vintage achieves the same.

Alice Lascelles is Fortnum & Mason Drinks Writer of the Year 2019. @alicelascelles.

Comments