Tanzania’s digital doctor learns to speak Swahili

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

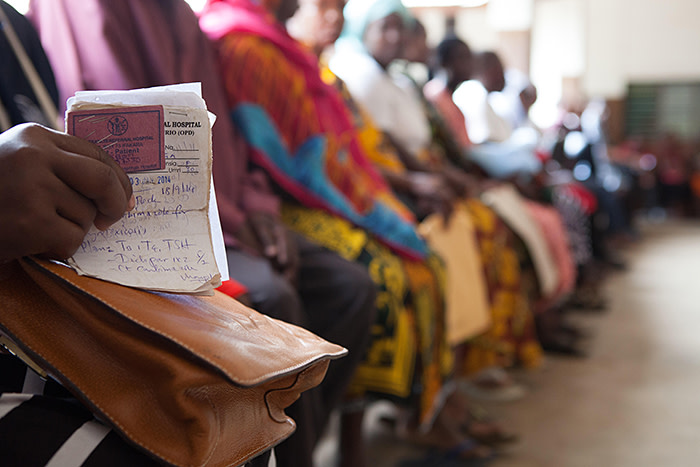

With one doctor per 25,000 people, the Swahili-speaking east African country of Tanzania struggles to serve the needs of its 59m people.

Life expectancy is 62 for men and 66 for women, while just two-thirds of the population live within 5km of a health facility.

“Traditional models will not fix this problem,” says Hila Azadzoy, managing director of the Global Health Initiative unit at Ada Health, a Berlin-based artificial intelligence-powered medical company. “Technology can empower users to take decisions about their own health by putting the power of AI into their hands,” she adds.

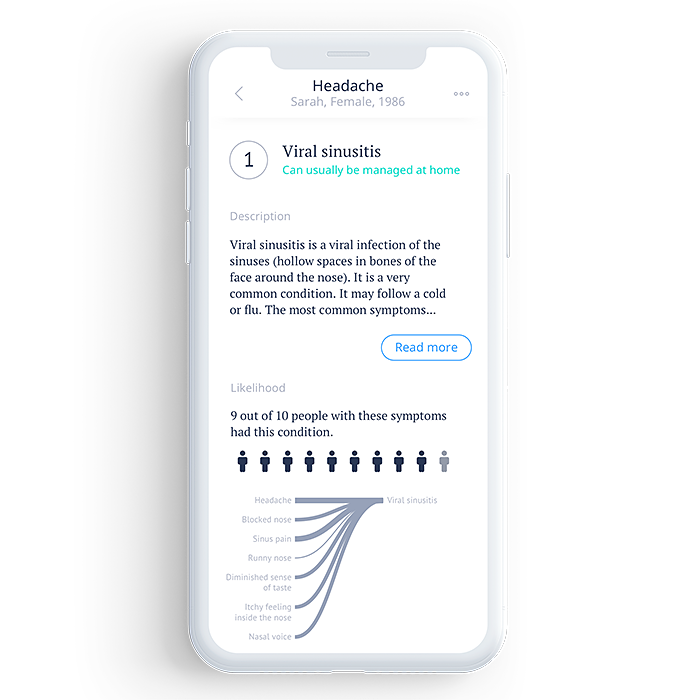

Available since 2016, Ada Health’s chatbot symptom checker app has attracted 9m users worldwide, including 3m in low- and middle-income countries. The free-to-download app invites users to input symptoms and pre-existing medical conditions before using AI-based questioning to pinpoint possible diagnoses — it then recommends next steps such as resting or seeking professional help.

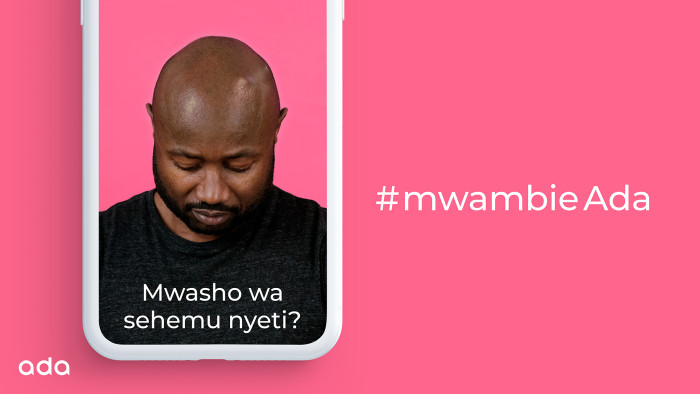

The digital doctor now speaks Swahili — the lingua franca of 100m people in east Africa — thanks to Ada’s Global Health Initiative. Launched last November, the project is aimed at improving access to healthcare in developing countries by offering reliable medical advice via its chatbot app.

Ada, which was designed in 2011 to help doctors in Germany diagnose rare diseases, now faces the challenge of integrating into a country hampered by poor infrastructure and a shortage of medical staff.

The app can help Tanzania overcome obstacles of low accessibility and unaffordable healthcare fees, says Nahya Salim, a lead clinician at Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences in Dar es Salaam. “The lower levels of the healthcare system are overwhelmed with too many patients and not enough resources,” she adds.

Salim, who partnered with Ada to build the app alongside Swiss non-profit group Fondation Botnar, believes it will improve access to healthcare by encouraging “timely and appropriate health seeking behaviour”, though the user base remains limited to young city-dwelling men. This is the demographic that is most likely to use smartphones, Salim explains, while adding that Ada must increase awareness of the app across the population. The company says it is working towards this. Its target is 1.5m users in the country by the year-end, although it is yet to reveal its current user numbers and only 7.5m Tanzanians own a smartphone capable of downloading the app.

Aidan Peppin, a researcher at the Ada Lovelace Institute in London, says that involving locals in the app-building process is vital to ensuring that Ada can integrate with the population. Ada Health says it has worked with local partners to make the app culturally relevant.

Despite the similarity in names — both a nod to 19th century British mathematician Ada Lovelace — Peppin’s institute is more sceptical about AI’s prospects for solving health problems. “These apps use a crude reductive process,” Peppin says. “In medicine there are too many unknown anomalies and AI can only deal with what it has seen before, it can’t make inferences.”

Sheena Visram, an associate editor at the Future Healthcare Journal and a clinical dietitian, agrees: “Digital health can supplement and enrich decision-making but it isn’t a silver bullet. Clinical decision-making is multifactorial, often with clinicians of different specialities working together to deliver patient care.”

Although trust and accuracy have been problems for various symptom checking apps, Ada acknowledges that it offers a “probabilistic assessment of possible causes for symptoms”, rather than definitive diagnoses.

Ada’s Swahili language app was built in a year by a 250-strong team, including 60 doctors, which prioritised diseases prevalent in east Africa such as malaria. While donors such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have financed Ada Health projects, the company also runs a for-profit model and has raised $69.3m from investors since 2011.

Replacing doctors is not Ada’s intention — instead it says it wants to facilitate interaction between users and healthcare experts while deterring unnecessary clinic visits by providing health information via smartphones.

Visram agrees that Ada can relieve pressure on Tanzania’s healthcare system by educating and triaging patients, but adds that training doctors and building hospitals must follow so that tech can be harnessed to improve health results.

Peppin concurs: “Unless tech is integrated with existing physical systems there’s a risk of creating serious health burdens and stretching existing infrastructure.”

Comments