London calling: Europe’s cities spark on-demand and travel start-ups

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It is almost 9pm as I drag my bike on to the pavement in central London, a Szechuan-style beef brisket swaddled in my delivery bag. I have spent the evening careening across town for Deliveroo, a start-up that specialises in ferrying hot meals from nice restaurants to people’s doors. I have already picked up Thai food near Tottenham Court Road and deposited it with a management consultant working late near Trafalgar Square, and scurried to Soho to collect an emergency consignment of bubble tea for students at the London School of Economics. Deliveroo’s algorithm assigns orders to nearby drivers via our smartphones, as we zip around on scooters or bikes to avoid the traffic. No leg of my journey has been more than a mile, and my best time from collection to delivery is just over eight minutes.

European Tech Entrepreneurs

Europe’s Top 50

Our panel picks Europe’s best talent

Interview: Daniel Ek

Spotify’s founder talks about what comes next

Watch out Silicon Valley

Skype’s Niklas Zennström on why Europeans have an edge

Top 10 under 30

The young tech entrepreneurs changing the way we work, play and buy

Europe à la mode

The continent is at the heart of fashion technology innovation

How did we pick them?

Judges considered factors such as innovation, impact and global standing

VIDEO: Founders Forum tech roundup

From flying cars to eye-tracking devices, what people got excited about at this year’s Founders Forum

PODCAST: Tech bubbles then and now

Brent Hoberman, creator of Founders Forum and co-founder of Lastminute.com, talks to Caroline Daniel, editor of FT Weekend

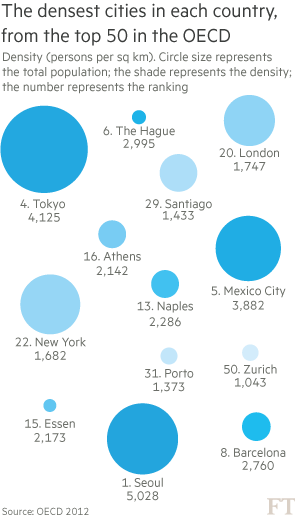

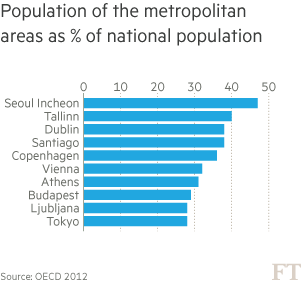

Observers of Europe’s technology sector commonly lament the lack of companies that rival Google, Apple or Facebook in size and innovation. But Deliveroo is one of a clutch of start-ups in areas such as travel, money-transfer and on-demand services that are capitalising on the distinctive features of Europe. The key to their growth? The fact that Europe’s cities are more tightly packed than their international counterparts. Of the 50 densest metropolitan areas in the OECD there are 22 in Europe — the same number as in Asia — but only one from the US: New York, which is still outranked by the likes of Barcelona and Liverpool.

Will Shu, a former American investment banker, co-founded Deliveroo in London three years ago. The idea was to create a better version of the “on-demand” food culture he had seen in Manhattan in the early 2000s, where a grid-based street system and a pool of cheap labour made it quick and easy for restaurants to deliver. When Shu moved to London in 2004, he was shocked by the lack of options for food on demand. “I ended up walking to Tesco or Burger King and getting something to eat,” he says.

Now Shu is using smartphones and cyclists to do for Europe what low wages and a logical streetscape did for Manhattan. The company charges about £2.50 per delivery. “We have a simple model: population density, restaurant supply and affluence,” he says. “When I think about our business I think about neighbourhoods, not even cities or countries.” So far Deliveroo has expanded throughout the UK and into Dublin, Berlin and Paris. On busy days in a single district of London, it processes close to 1,000 deliveries. Two-thirds of its customers repeat order, on average nearly 20 times a year. London in particular “lends itself to that kind of service because it’s more or less a collection of villages rather than one monolithic blob with highways”, notes Neil Rimer of Index Ventures, an investment group that has put money into Deliveroo.

Philipp Rode, the executive director of LSE Cities, a think-tank, says that many start-ups are thriving on “a shift towards inner-city appreciation — what we’re seeing is a return to the city,” he says. Increasingly, people prize perks like good transport, bike lanes, walkability and sustainability over owning a car or buying a big house. “There was a postwar obsession with suburbanisation and moving out of the city but now people are finding their way back,” says Rode. At the same time, smartphones — always on, always on us — have brought digital technology closer to people’s day-to-day reality. As a result, Rode reckons the next wave of technological innovations will come from companies that understand how people live in Europe’s metropolitan areas — “the hyper-urban condition created by public transport and higher-density living”, he says.

A vivid example of how to make the most of Europe’s landscape is BlaBlaCar, a Paris-based service that lets you hitch an intercity ride with people who are already taking a car. The company has 12 offices around the world and two million users a month, across countries including Russia, Turkey and India.

“If we’d started in the US, we probably would have failed,” says Nicolas Brusson, the founder and COO. One reason Europe was a good place to grow the company, he says, is that the distances are often manageable by road — rather than having to take a plane. Another is Europe’s superior public transport. “It makes it much easier to get into a car,” says Brusson. “If you’re in LA and you want to get to the Bay Area from Venice Beach, there’s no way to get to the pick-up point except by bus” — an unappealing prospect because of the decrepit service.

Bill Tompson, an economist at the OECD, says European cities tend to be denser because they are older, having emerged when everything had to be closer together to be accessible. “But then the automobile changed the way we built cities — and now we’re in deep trouble,” he says. Europe’s centres are also closer to one another, allowing people and ideas to cross-pollinate. “Europe’s advantage is not just the density of its cities but the density of the urban network itself — which depends not just on city size, but on connectivity,” says Tompson.

Several start-ups now use Europe’s transit network as a springboard for sophisticated journey-planning apps, like London’s CityMapper and Berlin’s GoEuro, which suck in data from buses, trains and trams to work out the best way to get from place to place. Naren Shaam, GoEuro’s Indian founder, was inspired to build his company in Germany after attending business school in the US. He saw how Europe’s web of cities meant that a greater proportion of the population travelled by train and bus — but that it was hard to understand how all the services fit together, especially when making international trips. “People in Europe get more vacation and they travel a lot more,” he says. “The cultural experience is different, too — I’m sitting in Berlin but a few hours later I can be in the Czech Republic or Rome.”

The inherent internationalism of Europe’s cities has helped spawn companies in areas such as cross-border communication and money transfer, the need for which is more apparent when you have lots of countries, currencies and immigrants coexisting. Skype, the internet calling service that Microsoft bought for $8.5bn, was founded in tiny Estonia — and its first employee, Taavet Hinrikus, went on to found TransferWise, a currency-transfer company in London. The opportunity for these businesses comes from being forced to look past their own tiny patch of turf and to treat the patchwork of Europe as a single entity, argues Brusson. “We sell as many phones, buy as much food,” he says. “The issue is that European companies fail to tackle it as a single market. Then along comes someone like Amazon and conquers us because they already have economies of scale from the US.”

Something that unites cities on both sides of the Atlantic is that they tend to be home to both the richest and poorest. On the way to my last Deliveroo order, I cycle past a foodbank serving homeless people dinner. Less than a minute later, I’m met at the door by a woman wearing a white satin nightgown, who tells me she uses Deliveroo at least three times a week. The cheek-by-jowl quality of European city life is undoubtedly a source of commercial opportunities — but it’s hard to escape the fact that there are some problems the start-ups have yet to solve.

Sally Davies is FT Weekend’s digital editor

Photographs: Jon Arnold / AWL Images; Alexander Babic; Dreamstime

Comments