How Salman Toor became the art name to know

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Last November, Four Friends by Salman Toor reached a new record for the artist at auction, selling for $1.5mn at Sotheby’s New York – far above an upper estimate of $400,000. The painting, which shows two men dancing in a New York apartment while two others sit looking on, sipping cocktails, has the elegance of a Watteau painting updated to 21st-century life. It’s one reason some have called the Pakistani-American artist’s work “Queer Rococo”.

Four Friends was a highlight of Toor’s breakout 2020 exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum, How Will I Know. He has since had institutional shows at the Baltimore Museum of Art and now at M Woods in Beijing, with the prices rising to match. Londoners will have seen his work in last year’s group show My Reflection of You at The Perimeter; next month they can see another in Close at Grimm (4 March to 6 April). “There’s something about the intimacy and sensitivity of Toor’s paintings that touches me,” says The Perimeter’s owner Alexander Petalas, who has several in his collection. It’s a sentiment echoed by the model Edie Campbell, an early collector of Toor’s work. “I find his work very moving… there’s a real crackle of energy to it.”

Much of this has to do with Toor’s reorienting his work toward the personal, celebrating the community he has made his own. Born in Lahore 40 years ago, the young Salman was a brilliant pupil and an excellent draughtsman, but he was also a self-described “sissy”, to the dismay of his conservative milieu. He went to Ohio Wesleyan in Delaware, Ohio, to study for a BA in Fine Art in 2002, before heading to New York, in 2006, to do a Masters, and for a while made a living as a painter of more classical, technically proficient paintings until he decided to start making work that spoke directly to and about him. It worked.

Today, Toor lives in New York. He became a naturalised American citizen in 2019; the new status mostly means ease of travel, he says, “although maybe it’s starting a family here” too. Currently spending time experimenting in the studio, he has agreed to be interviewed for HTSI on condition that the exchange is done as a Q&A. A droll, laconic talker, he is as happy delving into the state of contemporary Pakistani art as the horrors of Emily in Paris. Also, his dismay at Europe’s lack of air-conditioning. “We like to give emissions in the summer!” he jokes.

Poignant portraits of young men recur throughout your work. Did you, as a youngster, imagine the life and career you’d have today?

I didn’t anticipate this at all. I’m very lucky. When I started working here in New York, I was able to pay for an apartment through my earlier paintings. I showed in Karachi, I showed in Dubai; and to be honest, I think that it would have been OK to continue doing that. But this was a total surprise. I could never have imagined that I would have the studio that I have right now. I would have died if you had shown me the materials and the space, so it’s completely magical.

Your paintings often show moments of fleeting intimacy or connection; there’s often a sense of a threshold being crossed. Why do you keep returning to these brief encounters?

I grew up in a homophobic culture; I went to an all-boys’ prep school, and I also grew up in a pretty conservative, culturally Muslim family. There was zero visibility of forms of affection in public spaces. So yes, for me to do these paintings is to be on the verge of a threshold. But there’s another kind of threshold I’ve crossed in the near-20 years I’ve spent in New York. In 2006, when I came here from Ohio, this was a post-9/11 country, so there wasn’t any of the Gen Z discussion about gender or misogyny, things like that. The culture changed, and I changed. I felt like I’d been doing paintings that were very, very academic, and I wasn’t really interested in contemporary art. But I was skirting around the more meaningful things in my life, which was the struggle to be out, to make connections between the culture in which I was born and the culture that I have adopted, and the friendships that mean everything to me. So I decided to do other work in the studio. It was just bursting out of me.

What were the images that inspired you as a child?

My high-school friend’s parents collected art, and had libraries; my parents are not really readers. So I had access to the deliciousness of art monographs – Caravaggio and stuff like that. But my grandmother had a bunch of prints of paintings. She had a portrait of this white woman in a grey dress and grey hair, standing against a stone column; I found out later, when I went to college, that it was The Honourable Mrs Graham by Thomas Gainsborough. I just remember feeling something seeing these artists from Europe: from another part of the world, from a completely different time. There was a sense of this very tragic heroism – of finding both the romantic and the grisly. That was very valuable.

The Doodler shows a child hiding in a bedroom, drawing away; The Game has an ominous father figure standing, tense, over a small boy caught playing with dolls. Does making these pictures help you better face your past?

Yes, for sure. I feel like it gives me ownership. It’s a way of communing with people that are otherwise very difficult to commune with; a way of loving and liking things that are difficult to like.

A delicate, elongated nose characterises many of your figures. Why?

It’s about a sense of humour. A lot of the time, I might be painting someone really vulnerable, and I feel like if it was a pity party or too sanctimonious, it would just kill the painting. I want it to have a marionette feel: a little bit wooden, but at the same time someone who can be hurt.

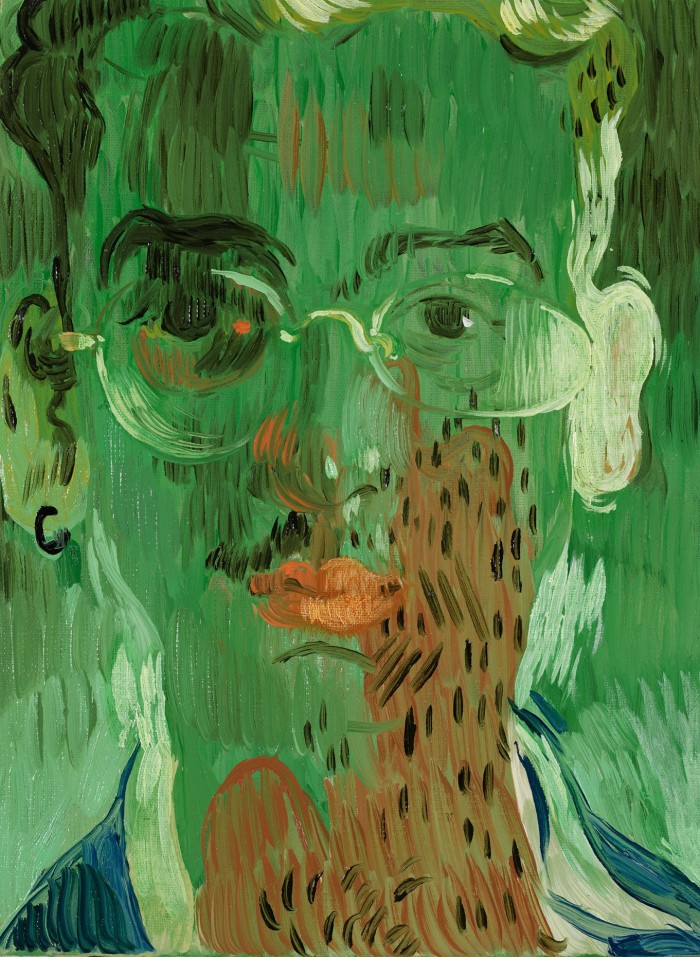

Your use of green in your paintings is also distinctive?

The two things about green that really get me going are that, first, it’s this very seductive way of looking at the world – a “through a wine bottle” kind of thing. But also, it’s got these cartoony, villainous associations I really like. Sort of toxic Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or absinthe, or Slytherin, or poisonous gas.

And now creamy, eerie yellows seem to be coming to the fore…

It’s a van Gogh palette of sickening colours! Anything that’s nauseating is good, because sometimes, if I feel like my paintings are verging on the quaint, I want to undo it. I’m like: “No! Vomit!”

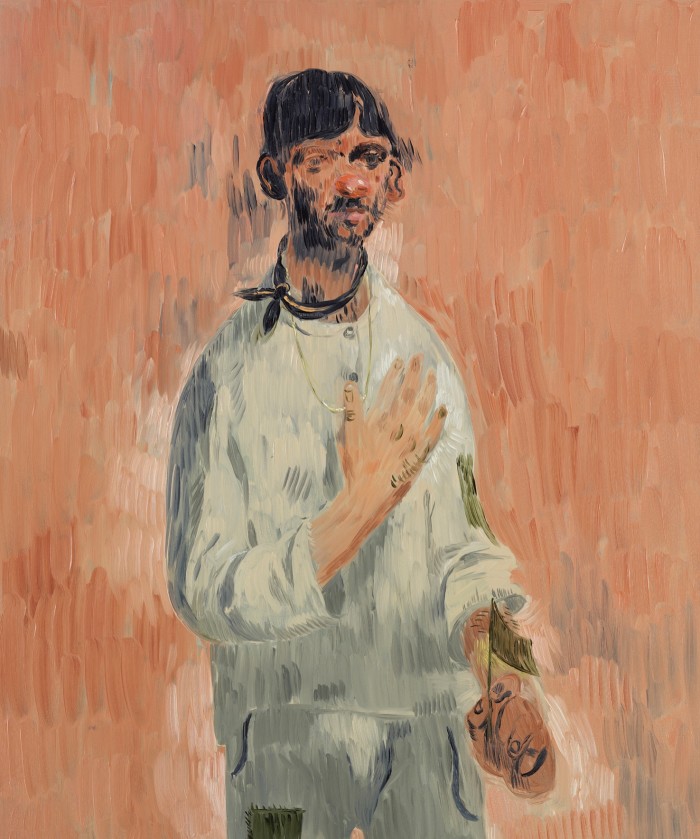

At London’s the Perimeter last year, viewers will have seen your Immigration Men; figures standing with their personal affairs laid out on a table in front of them. It’s a composition you return to again and again. Are they political?

I was interested in having both a sense of outer perception and an inner self-portrait. It’s about another threshold: that feeling that I still have – coming from one part of the world into this, the English-speaking world, or Europe, or whatever – that those two things are sometimes at war with each other. I guess I want the viewer to become the immigration officer and decide who should be let in – and why.

Apparently, your “intimate paintings are a salve for our isolated times”. Would you agree?

No! I would never think of my paintings as salves. I mean, a painting could be a salve for me, maybe, when it’s not driving me insane. But: no!

Figurative painting is back in fashion, but for a while it wasn’t. Did you feel like you were against the current?

Completely. When I graduated from Ohio and moved to New York, there were only a few artists doing it. But I guess, with the culture changing, from 9/11 all the way to BLM and Gen Z, personal stories have become so much more important. Also, with the rise of social media, everyone has to speak for themselves. Those stories, frankly, have changed the conversation in a way that I never thought it could be changed. That is incredible.

Do you think this change is here for good?

Oh, no, no, no, no…! It’s gonna go away. But I’m really enjoying it right now – thanks!

Is your latest museum show, at M Woods, a culmination?

It’s a continuation. I have been thinking of doing things like video, so we might see something like that. And I am finishing a graphic novel that I started with a friend seven years ago. I like the medium of painting, but the stories in the painting are equally important to me.

The title of your hit show at the Whitney stole from a Whitney Houston song. Should all exhibition titles be taken from Whitney songs?

No! I had a show in New York called Time after Time, and then I used a Sade title for my show at the Baltimore Museum: No Ordinary Love. I’ve done Sade, I’ve done Whitney… Maybe I should do Mariah? Actually, for the Chinese show they wanted me to do another song title, and I said: I’m done. So it’s just called New Paintings and Drawings.

Why the song titles though?

Lightness. The works do have to do with queerness and immigration and race, and I just didn’t want to drown them with heaviness.

Another feature of your work is your love of things – stocked dressing tables, buckled shoes, candlesticks and so on. Are you fond of arty clutter?

I am an aspirational minimalist, and I fail at it, but I keep trying. I’m a hoarder, but I like to organise. I actually cleaned last night, and I’m in a very organised apartment right now – it’s just giving me shivers of pleasure to walk around it.

How do you know if a painting has worked?

Ah – that’s simple. I have to refrain from taking a picture of it when a session is over – which takes six to seven hours, at least, because it takes me three hours to just control myself. After that, if I’m into it, I’m like: “I’m just gonna live here, I’m gonna die here in front of it, this is my life! I have nothing else to do.” But I don’t photograph it. When I come in the next day, I sit in front of it, I open my eyes – and I know.

Salman Toor: New Paintings and Drawings is at M Woods, Beijing, until 9 March

Comments