A passion for abstraction

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Long before it was even formed, the Schulhof Collection found its destination, one summer day in Venice in the 1950s. Novice collectors Rudolph and Hannelore Schulhof were staying at the Gritti Palace and witnessed one of the legendary sights of mid-20th century Venice biennales: Peggy Guggenheim, exotically dressed – on occasion she was swathed in gold lamé – being rowed down the Grand Canal in her private gondola. The next day the couple visited Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, where Guggenheim’s collection of Picasso, Kandinsky, Pollock was sometimes open to the public.

The Schulhofs were developing an interest in contemporary Italian art and stopped outside Guggenheim’s bedroom, arrested by an abstract composition. “We weren’t sure who the artist was, and I said it was [Giuseppe] Santomaso,” Hannelore Schulhof recalled. “My husband said it was someone else, and just then the door opened and she came out and said ‘You’re absolutely right!’ and then she invited us in . . . We started to talk about other artists, and she was very warm to us.”

The Schulhof collection of abstract American and European art from the 1950s to the 1990s begins, chronologically, more or less where Peggy Guggenheim’s modernist holdings end. It is an outstanding group of works: rigorous, restrained yet emotionally engaging pieces by prominent postwar figures including Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Ellsworth Kelly, Joan Mitchell, Frank Stella, Jean Dubuffet, Antoni Tàpies, Anthony Caro.

Following Hannelore’s death last February – Rudolph died in 1999 – the donation of more than 80 works to the Guggenheim, Venice, acknowledges the Schulhofs’ admiration of Peggy and the museum, and their love of Italy. A significant proportion of the pieces went on display in October; all will be fully shown, permanently, from May 2013. Their arrival represents a triumph of American-European and private-public relationships; at a stroke it transforms one of Europe’s loveliest museums, a light, bright, bizarrely single-storey neo-classical palace on the Grand Canal, into an institution that comprehensively covers 20th-century international art.

Everything about the Schulhof story, from acquisition to discrimination and focus to inspired bequest, is a model of a deeply considered, intensely felt private collection, with the couple’s intellectual yet grounded taste apparent throughout. The Schulhofs knew the artists they collected, explored their work in depth, understood their oeuvre. There are drawings by Philip Guston of exciting immediacy and directness, gifts of the artist. An ink drawing and collage inscribed “for Hannelore and Ruda” came from a visit to Eduardo Chillida in San Sebastian, complementing an early purchase, the taut oak sculpture, “Meeting Place”, a richly textural work that is also a fusing of geometric elements.

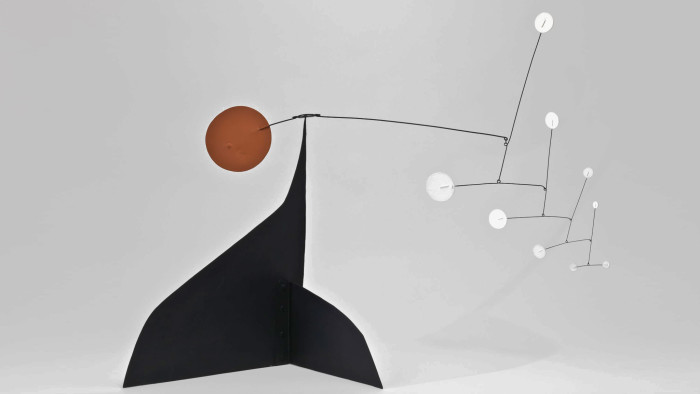

A fine late Rothko, “Red”, was bought from the Marlborough Gallery, Rome, after the Schulhofs visited the artist in his studio there, working with wide open windows to the strains of Don Giovanni. And several Calders – a moment of intersection with Peggy Guggenheim’s collection, which now has a superb range of mobile and static sculptures – were acquired during a friendship with the American artist. Hannelore used to dance with Calder on holidays with the Maeghts, the family of the legendary dealer, in Provence. The lyrical, majestically swaying “Yellow Moon”, which hung in the sun room of the couple’s home at Kings Point, Long Island, and the unlikely red-painted steel “Cow”, an abstracted figure seeming to pirouette, which now commands the Guggenheim courtyard, are among dramatic arrivals in Venice.

Calder embodies the existential force, grace and wit characteristic of this collection. The Schulhofs lived a charmed life and unashamedly loved beauty but, as refugees from Nazi Europe – Rudolf was born in Czechoslovakia in 1912, Hannelore in Berlin in 1922; they married in Brussels in 1940 before fleeing to New York – they remembered hardship and fear. Mental toughness, hard-won stability, sometimes a striving towards the spiritual are implied in the formal perfection of many of their works. “Art is almost like a religion. It is what I believe in. It is what gives my life a dimension beyond the material world we live in,” Hannelore said.

She recounted, according to the museum’s excellent catalogue, that the first work that “stopped me dead in my tracks” was a Jackson Pollock, encountered at a fundraiser at an ice rink in 1947. Intrigued, she took an art history course at the Museum of Modern Art; a few years on, when his greeting card business – supplying Catholic archdioceses – prospered, Rudolph took Hannelore to Justin Thannhauser’s Madison Avenue gallery to choose a present. A Rouault was selected, but Schulhof, unable to afford it, offered a lower price. Thannhasuer replied, “Look, you’re both so young. Why are you trying to buy the work of a dead artist? Why don’t you start collecting contemporary art?”

A business trip to Milan, where Rudolph opened an office, led them to the Galleria del Naviglio and Jean Arp’s bronze “Bust of Gnome”. The first painting they bought was Afro Basaldella’s abstraction “Yellow Country” (1957), fresh from the artist’s studio; in the 1960s they acquired Alberto Burri’s violent charred oil on masonite “White B”, also from the artist, and two “Concetto spaziale” paintings that are dazzling examples of Lucio Fontana’s equivocation between destruction and refinement.

Works by Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Robert Ryman followed in the 1970s, Tony Cragg and Anselm Kiefer in the 1980s, Jenny Holzer and Anish Kapoor in the 1990s. Minimalism is the unifying aesthetic, but not narrowly so, while the range of expression – calm and still (Agnes Martin) or agitated (Cy Twombly’s oil and crayon graffiti-like 1960s paintings), densely packed (Joseph Cornell) or rhythmically open (Robert Mangold) – dramatises the possibilities of the abstract idiom, diverse ways of balancing shape, colour, line.

In a market-driven, over-conceptual art world, the Schulhof Collection is a reminder of art’s lasting values and joys. The Schulhofs had no interest in individual trophy pieces, never sold a thing, displayed their collection at home, and gave one piece of advice: “Buy with your eyes, not your ears.”

Schulhof Collection, Guggenheim Museum, Venice, www.guggenheim-venice.it

Comments