Non-profits fill gaps in the broken market for antibiotics

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Push-pull action will be needed if the battle against antimicrobial resistance is to succeed.

The pull has to come from financial incentives to repair the broken market for antibiotics and make it worthwhile for the pharmaceutical industry to bring promising drugs to market. Yet despite signs that governments and the industry are beginning to tackle this — such as by finding ways to pay companies for developing drugs that will not be used under normal circumstances — there is still a long way to go.

But the push side is looking more encouraging. A ferment of research is producing new antibiotics, using technologies ranging from conventional “small molecule” chemistry to more biological approaches that enlist other microbes or viruses to attack harmful bacteria.

Philanthropic and government-backed organisations are supporting this research, funding academic teams and small biotech companies to take new antibiotics from discovery through pre-clinical testing and into early trials in human volunteers.

The global non-profit partnership Carb-X (Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator) has the largest portfolio. Governments and charities have provided it with $480m to invest between 2016 and 2022. It has so far funded 75 innovative projects, says Erin Duffy, chief scientist. “Our goal is to take programmes through first-in-human studies,” she says. “They can then be picked up for development and launch by other groups.”

One of the novel approaches supported by Carb-X is a project by Eligo Bioscience in Paris. It uses Crispr, the gene-editing technique, to alter the DNA of viruses known as phages that naturally attack and kill bacteria.

Eligo researchers will design phages to target and destroy antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the patient’s gut, without harming the beneficial bacteria that make up the human microbiome.

Once non-profits have developed promising drugs as far as they can, it then falls to others to bring them to market. An obvious candidate to do this is the new $1bn AMR Action Fund, launched in July and funded mainly by the pharma industry. Like Carb-X, it is based in the great US bioscience hub of Boston.

The fund aims to invest in 15 to 20 novel antibiotics — and bring two to four of them to market by 2030.

Besides Carb-X there are two smaller but still substantial funds investing in antibiotic research. One is the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) created in 2016 by the World Health Organization and Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi).

GARDP aims to deliver five new treatments by 2025, focused on the drug-resistant bacteria identified by WHO as posing the greatest threat to health and development. This includes babies with sepsis, sexually transmitted infections and hospital-acquired superbugs.

The third key investor in new antibiotics is the Repair Impact Fund set up in 2018 by Novo Holdings of Denmark, the business arm of the Novo Nordisk Foundation, which has screened 180 proposals and made nine investments so far. Its latest call for investment proposals, issued during the summer, has brought in another 74 submissions, says Aleks Engel who runs the fund — which is also based in Boston, the emerging centre of antimicrobial-resistance research. The various funding bodies compare notes and often co-invest in the same projects.

“The encouraging news for us is that we are seeing exciting innovations in the early pipeline that we hadn’t heard about before,” he says.

Asked which of the new approaches he is most excited about, Mr Engel chooses microbiome or “living therapies” that use benign bacteria to kill bad bugs. This is the technology adopted by Seres Therapeutics, also of Boston. It has a product called SER-109 in late clinical trials that consists of purified Firmicute bacteria in spore form. They are manufactured from bacteria extracted from the stools of healthy human donors, with potential pathogens inactivated.

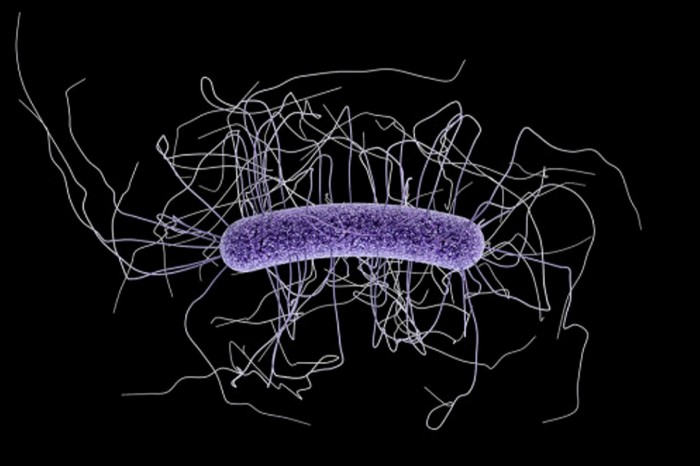

Studies show that SER-109 can reduce recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection, one of the most serious AMR diseases, by restoring the diversity of a health gastrointestinal microbiome.

“I would expect the FDA to approve Seres’s drug as the first microbiome drug,” says Mr Engel.

Like Ms Duffy of Carb-X, he believes the launch of the AMR Action Fund will make a big difference. “We are thrilled by this new fund coming to life,” he says. “Without it, we were afraid to have our companies stranded after phase 1 trials without enough investment.”

Even so, everyone involved in pushing new antibiotics out of the world’s research labs is counting on more action from governments and health services to pull them on to the market.

Comments