Can doubling down on basic skills rescue left-behind children?

Simply sign up to the Education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

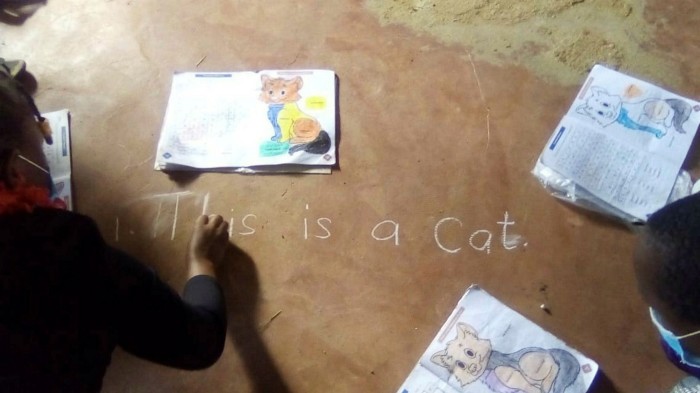

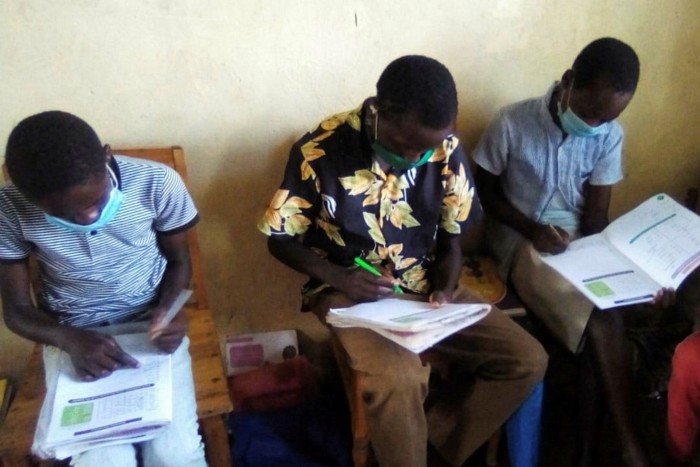

Every two weeks, Mercylona Sabwami, a teacher at Nalutiri Primary School in western Kenya, gives students five-minute written tests to see whether they have understood their English, Swahili and maths lessons. On Fridays and Saturdays, she tutors those who struggle, to help them catch up.

“They are often willing to learn but because of their background — poverty at home, their parents have separated, the lack of food, or basic needs — they can’t just settle in class and they end up dropping out,” she says. “We embrace them as our own children . . . so they feel school is a place where they can find peace of mind.”

Sabwami is part of a programme run by the Zizi Afrique Foundation which, since 2018, has joined a growing number of organisations in lower and middle-income countries implementing “teaching at the right level”. Developed in India, this approach uses simple assessments, followed by accelerated and individualised learning, to keep pupils on track.

Many educators believe such innovations are desperately needed. Despite a greater political and financial focus on education since the late 20th century — which has sharply raised school attendance — outcomes in some regions remain poor. According to The World Bank, more than half of children in lower-middle-income countries cannot read proficiently by their 10th birthday, rising to 90 per cent in low-income nations.

The proportions are scarcely better for numeracy, and the absence of these “foundational skills” in primary education undermines children’s progress through secondary school and into work. Fewer than 3 per cent of 15-year-olds in Cambodia, Senegal and Zambia have minimum proficiency in reading, according to the 2018 Pisa (Programme for International Assessment) study by the OECD in 2018, for instance.

This weakness has sparked intensifying — but far from unanimous — calls for policymakers, funders and international organisations to prioritise the “foundational learning” of literacy and numeracy in primary school. Proponents says this must be backed by better, more frequent measurement of attainment to increase focus and accountability — and drive improvement.

Professor Pauline Rose, director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning Centre at Cambridge university, says: “Foundational learning is absolutely the number one priority. It’s at the crux of the learning crisis. If you don’t tackle the problem of education in those early years, it’s really unlikely many children will be able to catch up. They drop out or learn very little.”

Professor Abhijit Banerjee is director and co-founder of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which has conducted rigorous testing of “teaching at the right level”. He stresses that there have been considerable achievements since 1990, when delegates at UN World Conference in Jomtien in Thailand pledged “education for all.”

“Thirty five years ago, if you talked about education, people would shake their head and say poor parents don’t want to send children to school because they don’t believe in it, it’s expensive and they want them for their labour,” Banerjee says. “But, since 1990, there has been a massive explosion of participation. The surprise has been that most children are in school, their parents are keen, and none of that pessimism held up.”

Budgets have risen, helping the construction of new schools, the recruitment of teachers and the purchase of books in most parts of the world. The result has been a surge in attendance — including a sharp rise among previously excluded groups, including girls, the disabled and marginalised rural and poor children.

But that success in quantity has overshadowed quality, with growing class sizes often leaving teachers struggling to give sufficient attention to individual students. Depending on the system, some pupils can move automatically into higher grades without the basic skills needed for more advanced learning; others stay at the same level and become demotivated.

Luis Crouch, senior economist with RTI International, a non-profit research group, says: “If you don’t get the foundations right, they won’t complete. If you sit in Grade 1 for two years and Grade 2 for two years, that’s four years gone by and the kid will drop out.”

Crouch calls for an overhaul of unproductive, old-fashioned teaching methods that focus on rote learning and memorisation rather than processing and understanding. Those often include teaching in the languages of former colonial powers — notably English and French — which are remote from children’s everyday lives. Others cite a broader legacy of curricula and education systems focused on elites.

Not everyone is convinced that foundational learning is a magic bullet. Despite multiple pilot programmes that have been rigorously tested, and demonstrated local success, few have scaled up successfully across a region or a country — let alone across different parts of the world. Outcomes overall remain disappointing.

Drawing on recent studies of children in Ethiopia who have returned to school after they were shut by coronavirus last year, Cambridge university’s Rose stresses that “early years” education is also important. Children who attended pre-school were better prepared to learn in school and to catch up on their post-Covid-19 return.

David Archer, head of public services at ActionAid, the development charity, cautions: “An excessive focus on literacy and numeracy alone can be counterproductive, especially in the early years when social and emotional development and a range of non-cognitive skills should also be considered foundational.”

Such views have led to ambivalence, including a suspicion by teachers’ unions that a focus on literacy and numeracy performance can lead to gaming, manipulation and a reductive assessment of teachers and schools. Ministers also face pressure to tackle the more immediate concerns of secondary students seeking work.

International organisations such as Unesco and the UN-backed Global Partnership for Education have been reluctant to prioritise too far, stressing instead countries’ autonomy and the greater funding required to meet all the objectives of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal for education.

Yet with domestic budgets squeezed following the pandemic, and some donors such as the UK cutting back help, others suggest that a doubling down on foundational learning is needed to achieve further progress.

Lant Pritchett, director of the Research on Improving Systems of Education programme at Oxford university, argues that many school systems fail their elites, let alone disadvantaged groups. He calls for stronger but nuanced accountability, with systems that measure outcomes more than inputs, and which emphasise the value of teachers and reward innovation.

Robert Jenkins, education chief at the UN Children’s Fund, instead stresses “formative assessments” — low-stakes, regular testing to help support teachers such as Mercylona Sabwami in Kenya. “The focus should be at the school level,” he says.

For him, “summative assessments” can follow, to track the performance of children across whole school systems and drive broader improvement. Longer term, finding ways to harmonise and integrate the two types of measurement — perhaps with the help of technology — will be pivotal.

For now, children, parents and policymakers alike are relying on teachers like Sabwami, who says she is driven by a passion because “if I don’t help, God will punish me because a learner will not be helped and will end up quitting rather than embracing education.”

Improvement on a larger scale will require greater human, as much as divine, oversight.

Comments