Dada meets Dostoyevsky: William Kentridge in Basel

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

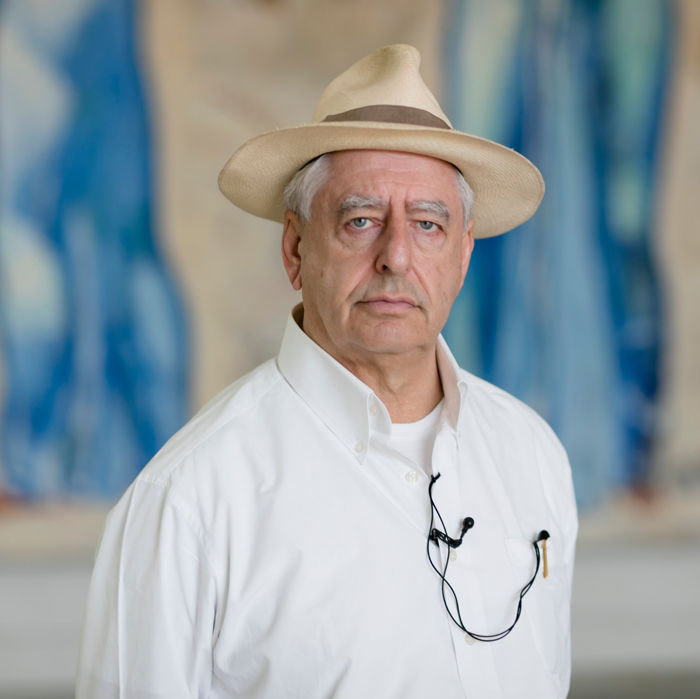

William Kentridge contains multitudes. The South African artist draws, films, writes, directs, performs, makes and collaborates. Often all in the same work. His touch — think Dada meets Dostoyevsky — is feather-light but his grasp of politics, science and history is heavy.

As such, his work requires a less-is-more curatorial approach. His best shows feature a smattering of his different media — drawing, film, performance — and give the viewer time to dwell among the millefeuille of his sensibility. Pace yourself then at his new, marathon retrospective A Poem That Is Not Our Own, which opened at Basel’s Kunstmuseum this week.

The bulk of the show, which unfolds over the institution’s three spaces, is installed in the Gegenwart building. It starts with a timeline which weaves Kentridge’s own life story into his country’s history of apartheid and eventual transition to democracy. His experience of that tortuous journey has made the artist, whose father Sydney Kentridge was a legendary civil rights lawyer, one of the most eloquent blame-singers for his country’s decades of injustice.

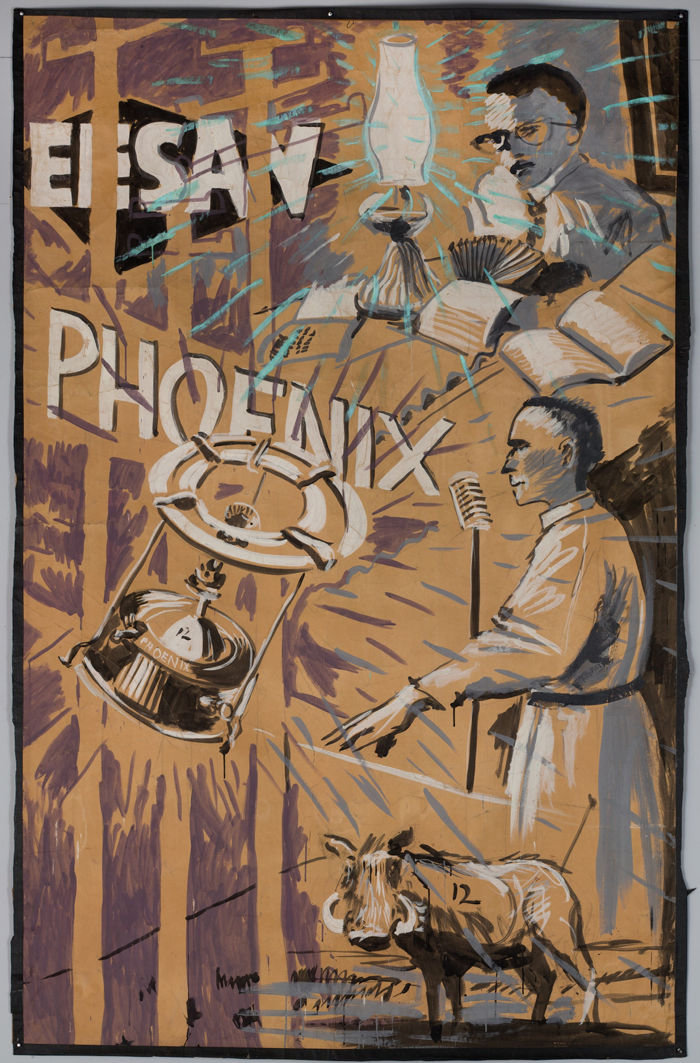

Thus we learn that Kentridge was born in Johannesburg in 1955, the year that residents of Sophiatown, a district that was a flourishing hub of black culture, were forcibly evicted under the Natives Resettlement Act of 1954. This sets the scene for “Sophiatown” (1986-89), a sequence of backdrops Kentridge made for the eponymous stage production by the Junction Avenue Theatre Company — a rare example of a multiracial ensemble — which recounted the Sophiatown eviction.

In chalky-white and black gouache on brown paper, many of these images have never been shown before in Europe. With their kaleidoscopic melange of advertising slogans, music scores, clocks and figures (a horn-playing typist, a shadowy man in a hat), they are embryos of the startling visual collisions that are Kentridge’s alphabet.

But spare a moment, too, for the documentary film that accompanies them. Entitled Freedom Square and Back of the Moon (1986), it was co-directed by Kentridge and Angus Gibson. As well as clips of Sophiatown on stage, there are interviews with men who grew up there, such as the ex-gangsters who speak wistfully of their memories of snappy outfits and amiable muggings. So much more linear than Kentridge’s later work, this elegy for a community smashed by white fascism reveals the abyss of emotional loss which the artist usually buries under his madcap surrealism.

Reinforced by the meticulous timeline, Kentridge has never left his audience in any doubt that it is the Kafkaesque history of 20th-century South Africa which underpins his work.

Right now, however, as the wider world slides into dystopia, he looks like the prophet for a bigger picture. In particular, he bears witty yet sensitive witness to the confusion so many of us feel as we struggle to balance our interior worlds with the current state of global politics and the welter of information which accompanies it.

A sequence of his notebooks and drawings from 1976 to 2018 — which features his beloved Moka espresso machine (a regular actor in his oeuvre) and the musing, “What am I? I am one of my sensations” — show the irreconcilable coexistence of the everyday with the existential that is quotidian reality.

As he matures, his handling of contradiction has grown both bolder and more delicate. At Basel, he unveils “Kaboom!” (2018), a three-channel film installation that has been adapted out of his performance “The Head and the Load” (2018), which premiered at Tate Modern last summer.

As so often, he shoots his characters as anonymous shadows, obliged to dance like puppets to a dissonant soundtrack while fragmented sentences proclaiming “this is not true” float around them.

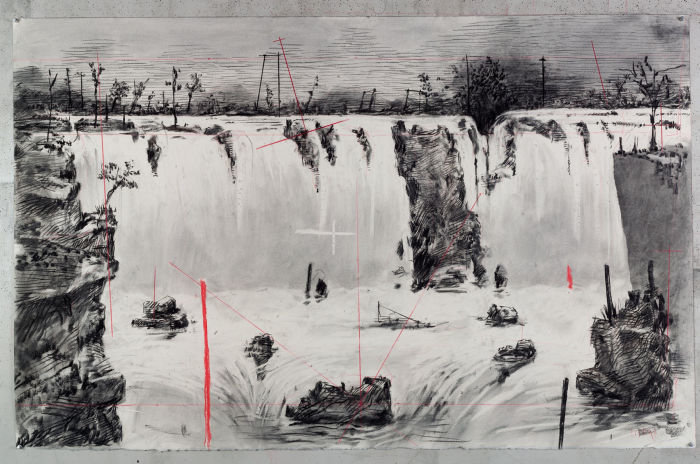

In truth, the kernel of “Kaboom!” is the thankless service of two million African porters and carriers used by Britain, France and Germany during the first world war. Against maps of colonial Africa, Kentridge pastes snippets of army lists — 31 are out of action for disease; 344 pairs of mittens. Meanwhile random scribbles in red pen — we see him drawing frantically in the film — testify to the artist’s hopeless effort to make sense of war’s cruelly scrupulous chaos.

Kentridge’s observation that the “sound of rational argument [is] hiding a deep irrationality” is elaborated in his newest work. Never shown before, and still “in progress”, “The Mouth is Dreaming (work in progress)” from 2019, is a two-channel video installation that proffers a borderless, entropic world.

Dissolving from derelict classical museum to barren mining landscape, from animal to miner, theatre to studio, this is an animated planet of mysterious forces where birds draw their own flightlines, and fountains of blue ink flood charcoal hills.

The artist is everywhere and nowhere; peering hopefully into a museum vitrine, then morphing into a coffee pot; trying to draw with both hands at once, while a miner chips indifferently between them. His red pencil marks intrude again in an effort to exert control, but there’s no stopping a world where too many horses — colonialism, capitalism, the mirage of international development — have already bolted.

In the midst of the Basel Kunstmuseum’s permanent collection, Kentridge has installed the film “Drawing Lesson 50: Learning from the Old Masters (In Praise of Folly)” (2018). Here he watches himself draw at a table, mystified by his alter ego’s practice. “But what is the responsibility of the artist?” he asks, and to his fury receives a reply in Latin.

“He would have been better advised to be a mender of shoes,” is his damning judgment on himself. Such psychic splitting is a symptom of a world that’s out of joint. But the breadth, courage and relevance of his mature work leaves us fervently hoping Kentridge won’t take his own advice.

To October 13, kunstmuseumbasel.ch

Comments