Bangladesh smartphone keyboard sparks political controversy

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

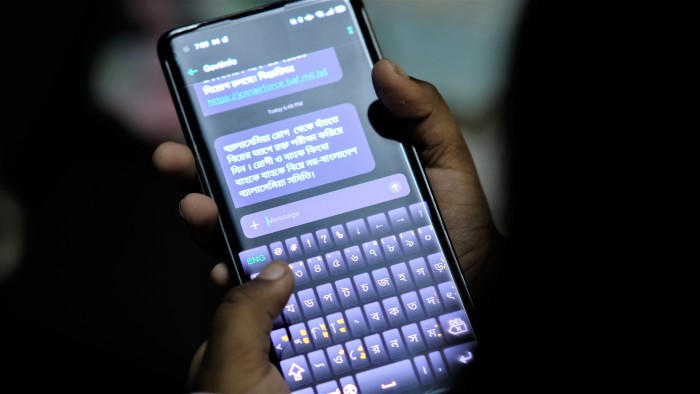

Bangladesh’s telecom regulator has made it mandatory to install a particular Bangla-language keyboard in all Android smartphones sold in the country — a controversial move given that the company that produces the keyboard is owned by the incumbent telecom minister.

The keyboard software in question is called Bijoy, which means “victory”. It is made by Ananda Computers, a company formed more than three decades ago and owned by Mustafa Jabbar, the minister of post and telecommunications.

Although Jabbar has denied any wrongdoing, watchdogs said the issue was part of a troubling larger pattern in Bangladesh, while industry players said the directive created a hassle in a market that is home to about 170mn people.

Bijoy is considered the first successful commercial Bangla keyboard layout and Jabbar is credited with designing it in the late 1980s. After decades of selling the keyboard layout for PCs, Ananda Computers released a version for smartphones.

In January, the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) — a division under the control of Jabbar’s ministry — issued an order to the country’s mobile phone importers and manufacturers that they would not be issued “no objection” certificates to sell smartphones if they did not have Bijoy pre-installed in their products.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

On January 24, local media reported that an attorney had sent a notice on behalf of Mohiuddin Ahmed, president of the Bangladesh Mobile Phone Consumers' Association, demanding that the directive be withdrawn and threatening legal action if it was not.

The Bangladesh chapter of Transparency International, a global corruption monitor, sees the directive as a blatant use of state power for personal profit and said such a move would disrupt the market and create an uneven playing field for competitors.

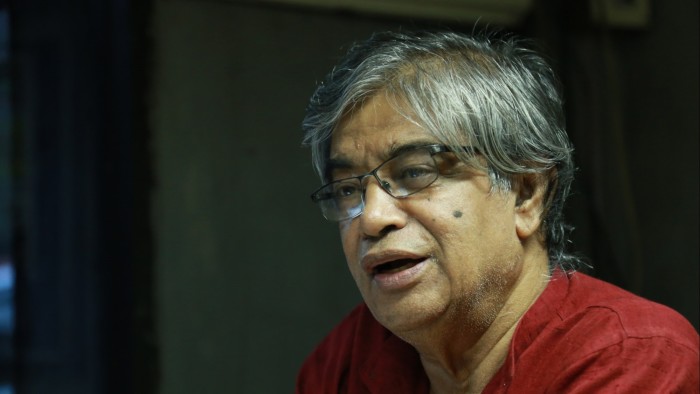

Bangladesh is no stranger to corruption, according to TI, which ranked it 147th out of 180 countries on its latest corruption perceptions index — the worst in south Asia after Afghanistan. While graft usually comes in the form of underhand dealings or shell companies, Iftekhar Zaman, executive director of TI Bangladesh, suggested this might be the first time “a person of such power openly misuses his position for personal gain”.

Jabbar, known as a tech pioneer in Bangladesh, insisted he was doing no such thing. “I run a government office and I just help implementing a government-prescribed standard,” he said. “It’s nothing but my duty.”

The minister, previously the top executive in the largest private associations of both software and hardware companies, explained that the current national Bangla keyboard standard — which uses the Bijoy layout — was approved five years ago by the Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution, the government agency that provides standardisation certification.

“So, BTRC just asked to keep the standard keyboard in the smartphones from now on,” he said. “There is no wrongdoing here.”

Under the constitution, certain office holders including cabinet ministers are prohibited from maintaining lucrative positions in private companies. They are expected to renounce their executive roles upon taking office, though this is not always done in practice. In Jabbar’s case, he is still the proprietary owner of Ananda Computers, but the day-to-day operations are handled by others.

In any case, Jabbar insisted that since the Bijoy keyboard Android package kit — a file format used to distribute smartphone software — could be obtained for free from the telecom regulator, the rule would not benefit him.

“Why [is there] a notion that I am doing that for my business gain?” he said. “I am not making money out of it.”

Critics said it was not that simple.

Some noted that despite its long history, Bijoy was one of the least popular Bangla keyboards for Android phones, which dominate more than 90 per cent of the market according to the Bangladesh Mobile Phone Importers’ Association. Even if it was free, they said that if Bijoy was mandatory, Jabbar’s company would still benefit in other ways.

Before the directive, Bijoy had been downloaded more than 50,000 times. As of Sunday, that figure had surpassed 100,000. But both numbers pale in comparison to the more than 50mn downloads of Ridmik, the most popular keyboard option. Ridmik Classic, another layout from the same competitor, had been downloaded more than 10mn times.

Bijoy also had a much lower average user rating than Ridmik. Officials from Ridmik Labs declined to comment when asked for their reaction to the government directive.

“So, now Bijoy will have access to huge [amounts of] users’ data, which is of course a very valuable, sellable product,” said Md Assalut-uz-Zaman, an expert on information technology. “Besides, the worth of the free marketing it gets is immense . . . A product which historically did poor business now gets a boost courtesy of a government directive,” he said.

Zaman, who runs a company that produces business analytics software, said Bijoy’s ownership would surely benefit from being tied to the roughly 9mn new Android smartphones that enter the market annually — a figure confirmed by the BMPIA. More than 85 per cent are now locally manufactured or assembled by a total of 14 companies.

Zaman said that a product such as a keyboard, virtual or physical, could be standardised by the national agency but that did not mean the government could intervene to make a particular one compulsory for users. “The tech world doesn’t function that way, especially in an open economy under a democratic government,” he said.

An official at the Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution said that out of 4,500 standardised products and services, only 229 were on a “compulsory list”, none of which were keyboards. That means there is “no obligation from the government” to make it mandatory, the official added.

Mobile phone manufacturers, meanwhile, say the directive will create technical difficulties for them and increase costs.

Rizwanul Haque, vice-president of the Bangladesh Mobile Phone Importers’ Association, said Android usually had the same Android package throughout the world. “It means we will need to pay a certain fee to Google to bring in the Bijoy APK (Android package kit) during the manufacturing stage,” said Haque, also the owner of a company that assembles three different Android smartphones in Bangladesh. “It obviously is a hassle.”

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on January 25, 2023. ©2023 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved.

Related stories

Archrivals China, India move in to fund same Bangladesh port

India’s top court rejects Google plea to block Android ruling

Apple hires workers in India as it looks to open first flagship stores

Comments