Why Germany’s energy package is undermining EU unity

Simply sign up to the EU energy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

European leaders have been quick to condemn Germany’s bumper energy package, claiming that Berlin’s decision to go it alone puts households and companies in the rest of the bloc at risk of paying higher energy prices.

Mario Draghi, Italy’s outgoing prime minister, has said the €200bn package, unveiled last week, undermines unity. “Faced with the common threats of our times, we cannot divide ourselves according to the space in our national budgets,” he said.

France’s finance minister Bruno Le Maire and his Irish counterpart, eurogroup chair Paschal Donohoe, have echoed Draghi’s calls for a more co-ordinated response. They were joined on Wednesday by Ursula von der Leyen, the EU commission president, who has called for a bloc-wide ceiling on the price of gas — a measure Germany has objected to.

Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán, who has spent much of this year locked in disputes with Brussels, has been even more critical, decrying the package as “cannibalism”. Orban called out the measures for falling foul of EU rules on state aid by helping German companies “with hundreds of billions of euros” at the expense of rivals elsewhere.

Are claims that Berlin’s package is outsized correct?

Germany’s finance minister Christian Lindner may have insisted that the Comprehensive Protection Shield is “proportionate” to the size and vulnerability of the German economy. But, by any reasonable standards, the package is large.

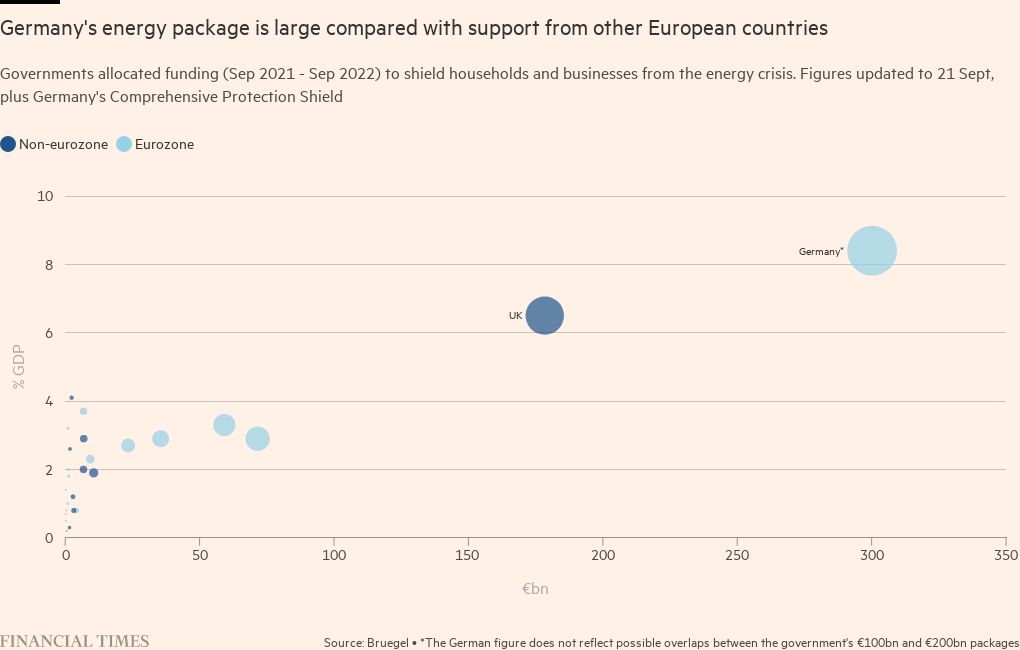

The €200bn plan, much of which will be financed with debt, corresponds to 5.6 per cent of the country’s economic output in 2021.

Although Lindner has said the package will cover two years of spending, it comes on top of the €100bn of support already allocated by Berlin. Between the two packages, German companies and households could receive 8.4 per cent of gross domestic product in energy subsidies, though there may be some overlap.

Together, the €300bn figure is more than double the financial support provided by Italy and France combined, the region’s largest economies after Germany. In GDP terms, the package is at least three times as big as the support offered by most other eurozone countries.

Antonio Fatas, professor of economics at INSEAD, said the size of the package “raised valid questions about whether this constitutes state aid in support on its business”.

The figures announced are a cap, however, and the German government could end up spending less should energy costs fall. This is indeed what happened in the case of the country’s Covid-era economic stabilisation fund, which was also criticised by member states for its largesse. The fund had an original limit of €600bn to bail out companies hit hard by the pandemic, but has only used around €50bn of the funds available.

So what is Germany’s justification for such a large package?

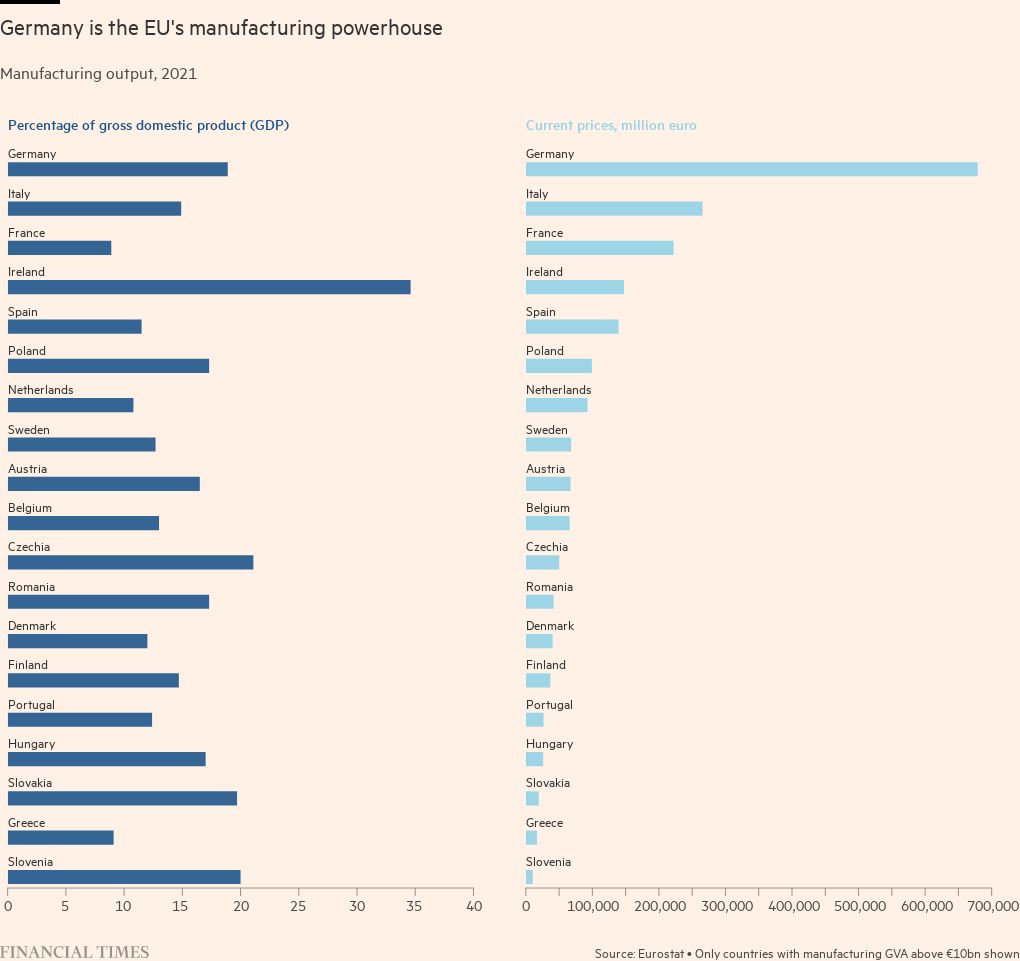

Germany is the eurozone’s manufacturing engine. Its factory output in 2021 was larger than that of Italy, France and Ireland combined.

Its energy-intensive companies have, therefore, been hit particularly hard by the impact on energy costs of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Some defenders of Germany’s policy say this justifies its fiscal largesse.

Others argue that, while a pan-Europe solution to the energy crisis would have been the best solution, the package would benefit other countries in the region — especially those with close trading relationships.

“It is still preferable to lack of fiscal support at all and a deep economic contradiction in Germany,” said Silvia Ardagna, chief European economist at Barclays Bank.

“It is in no EU country’s interest, given close trade ties within the single market, to have Germany’s economy weaken excessively,” said Sandra Horsfield, economist at Investec, an asset manager. “A massive terms of trade shock [such as the European energy crisis] leaves only undesirable options on the table. It is a matter of choosing the least bad among them.”

Will Germany’s package lead to higher prices elsewhere?

That is possible. Nick Andrews, Europe analyst at Gavekal Research, argued that by lowering bills, the German package is likely to result in stronger demand, pushing up gas prices on Europe’s wholesale markets.

“While German companies will benefit from lower energy prices, their counterparts across much of Europe will pay more, undermining their competitiveness,” said Andrews.

Berlin claims that the package will maintain the incentives to save energy as it will only subsidise a basic allowance of gas and electricity. It would also have to comply with state aid rules on energy subsidies, which were revised in July.

The package could also complicate life for the region’s policymakers.

Energy is the main reason why eurozone inflation reached a fresh record high of 10 per cent in the year to September, more than five times the European Central Bank’s 2 per cent target.

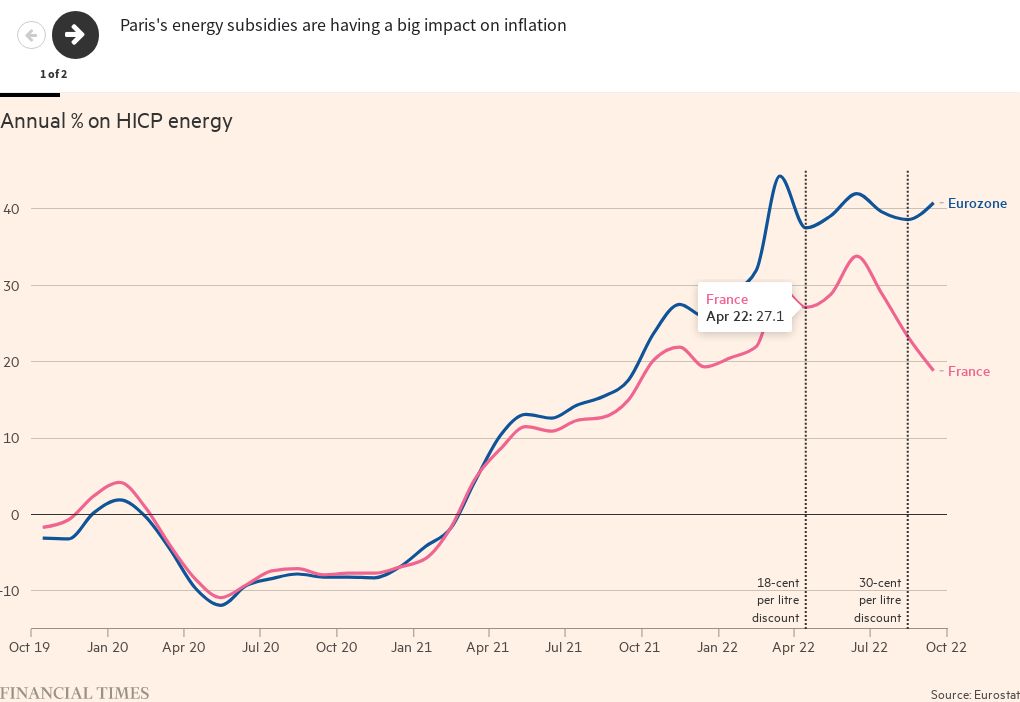

France’s 30-cent per litre rebate on the price of fuel at the pump that came into effect in September, nearly doubling the previous rebate of 18 cents introduced in April, combined with the maintenance of a tariff shield on gas and electricity prices, pushed down energy inflation to below 20 per cent in September — far lower than the eurozone average.

Given the size of Berlin’s package, the divergence in inflation between Germany and the rest could be even greater. A one-size-fits-all monetary policy would, Andrews said, become “more challenging to devise and a great deal less effective in execution, adding to the fragmentary forces at work in the eurozone”.

Does the package raise the risk of a market panic?

Since Germany launched its programme, its borrowing costs have fallen. Other countries are not in such an enviable position.

The market turmoil in the UK, triggered by unfunded tax cuts, is a reminder of the perils that many countries are facing if they try to support their households and businesses with greater generosity.

Yet, with Germany refusing to co-operate on EU-wide gas caps, some countries, particularly in eastern and southern Europe, may end up with little choice but to risk a borrowing crisis and spend extra funds to subsidise households and businesses.

Claus Vistesen, chief eurozone economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said national initiatives were justified because “the EU can’t act quickly enough”.

However, Fatas said, while co-ordination was difficult, given the severity of what Europe potentially faces this winter, there was “no other way to move forward” than a common solution.

Comments