Has the restitution debate undermined the market for African art?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“A tidal wave of change is coming” to the market for African art, according to Adenike Cosgrove. She is the founder of Imo Dara, an independent website established to connect collectors of African art with reputable scholars and dealers, an initiative that responds to the ways in which the urgent worldwide concerns over the past looting and theft of classical African art now impact on the market in similar historical works.

The “imminent shift in taste” she identifies on the horizon is one spurred just as much by the recent boom in the market for Modern and contemporary African work as it is by the knock-on effects of debates over the return of colonial-era plunder. These are developments that are almost always considered in isolation, but Cosgrove is part of a growing school of thought that recognises both as tributaries to a broader whole.

Last year, Imo Dara’s State of the African Art Market report included analysis of both camps — classical African art and Modern and contemporary. Debates over restitution have had a clear effect on the former market; Cosgrove identifies that, of 355 collectors surveyed, 29 per cent believed they would shift away from collecting classical African art, while 37 per cent believed that it would become more difficult to sell such works in years to come. Meanwhile, there has been a wave of new collectors from Africa entering the market for Modern and contemporary work.

That is not to say that the market for classical African art is on its way out. Cosgrove stresses that, while high-profile cases of looting dominate press headlines (chiefly the Benin Bronzes), the vast majority of works on the market today would have been given as gifts or freely sold. “It is important not to deny the agency of the African in these transactions,” she says, adding that is also important for the small coterie of respected and established dealers and collectors in this field, well represented at Tefaf, to define clearly what is loot and what is not.

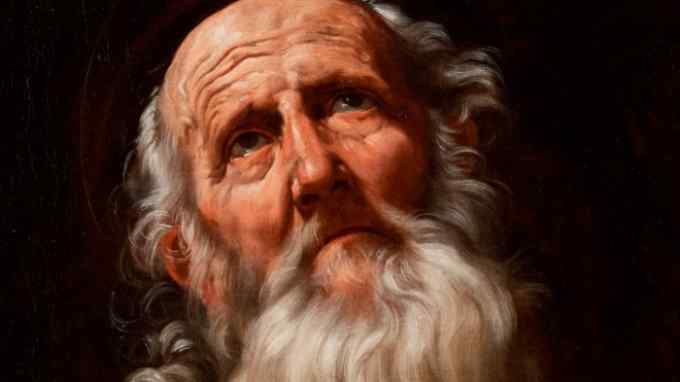

“We have to listen to the descendants of the creators of these great objects,” says Bernard de Grunne, who runs a long-established dealership in the Sablon district of Brussels. He suggests that “some museums are nervous” about restitution, but emphasises that for his collector base, assurances as to provenance and authenticity of the works he deals in are cast-iron. “The established corpus of masterpieces has been known for at least 40 years and I do not believe there will be new major discoveries coming out of Africa,” he says. That means collectors and dealers have less cause to confront fears of more recently looted objects that are currently plaguing the antiquities market. De Grunne brings to Tefaf a collection of Mumuye sculptures from Nigeria, remarkable for their use of negative space.

Serge Schoffel, also based in Brussels, is more nervous about the impact of restitution, speaking of a new “hesitancy” on the part of collectors to enter the market. But he says that it has historically been the job of dealers to “raise African art to the same level as western art” and that in this regard nothing has changed. Alongside works from Papua New Guinea and New Island, he brings to Tefaf sculptures from Sierra Leone, Gabon and Nigeria.

Lucas Ratton in Paris, who comes from a long line of African art dealers, including his famous great-uncle Charles Ratton, speaks of the “positive effect” of greater attention to provenance research. “The market has become much more focused in the last 10 years,” he says. “I would feel very safe in the market as a buyer today.” Ratton is one of a younger generation of dealers who are diversifying their offering, presenting African artworks alongside international Modern and contemporary art and design. A highlight of his display at Tefaf is a magnificent fetish figure made by the Songye of Gabon, which he bought at the high-profile Périnet sale at Christie’s last year.

For Parisian dealer Bernard Dulon, “the future of the market will be very good” — not least because “the most important developments of the next century will obviously be in Africa”. Collectors from Africa, he says, are “just at the beginning” of entering the market for classical works. For Dulon, restitution is less “a legal issue than a moral one — because many countries in Africa have no access to their past. But soon they will be rich — and they’ll be buying it back.”

At Tefaf this year, there will be a booth dedicated to more recent works of African art. Ayo Adeyinka of Tafeta gallery deals in Modern and contemporary works, predominantly by Nigerian artists. Most of his collector base, he says, resides in Africa, and “African collectors have always collected classical African art alongside [African] Modern and contemporary,” he says. For now, the dealers in older material at Tefaf are more likely to point to the entry into the market of collectors who want, in Dulon’s words, a “fantastic sculpture to go with their Rothko”.

But Adeyinke highlights younger dealers of traditional works who have begun to sell contemporary African work alongside their usual fare as evidence that the “longevity” of the African art market lies in its ability to diversify — a trend which Cosgrove also highlights. As institutions in Europe and the US are looking to plug gaps in their collections of Modern and contemporary African art, and new museums springing up on the African continent are seeking to bridge traditional and modern art forms, both Adeyinke and Cosgrove predict that private collectors and dealers will shift their habits to present a more holistic narrative of African art history.

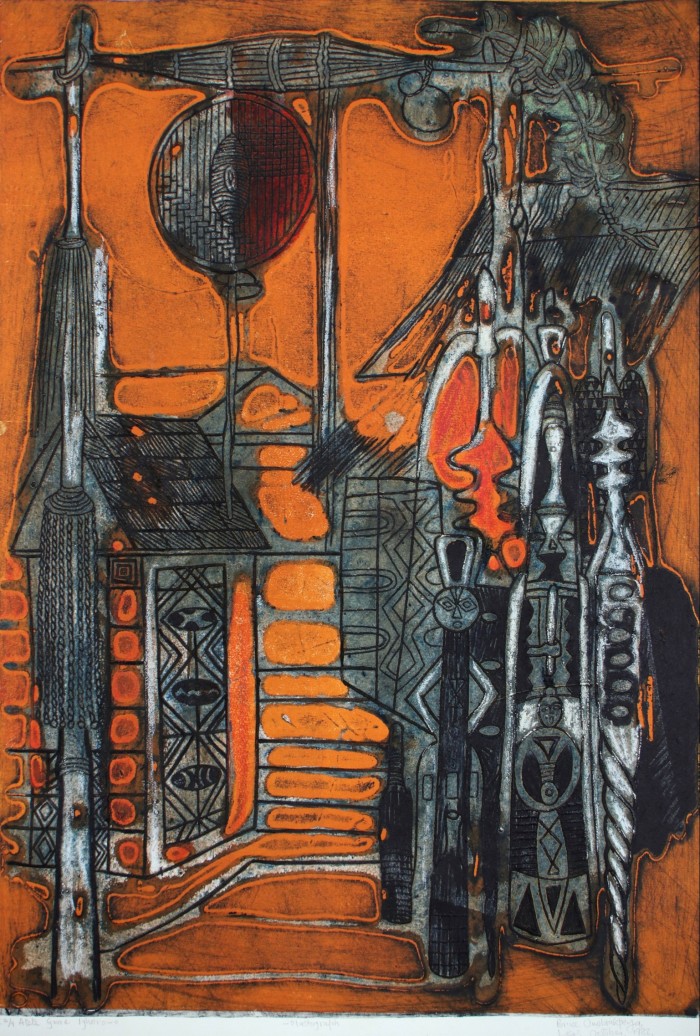

Tafeta’s stall includes a sculpture by Bruce Onobrakpeya, now in his nineties and receiving his first US museum retrospective at the High Museum in Atlanta later this year, as well as a drawing by Uche Okeke (1933-2016), whose work has recently been acquired by MoMA. Both of these artists were profoundly influenced by the aesthetics of the precolonial past. Tefaf visitors this year have a rare opportunity (in the west) to see modern African works in proximity with the traditions to which they responded. There are welcome signs that, before long, such opportunities will become rather more common.

Comments