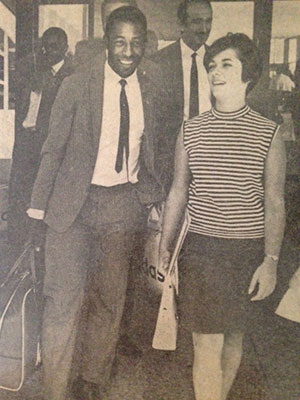

Making friends with Pelé

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the 1960s, hardly any academics – and certainly not female American sociologists – took Brazilian soccer seriously. But I did. I eventually published the first academic study of the Brazilian people’s passion for football – and formed a friendship with Pelé that still endures.

My interest in Brazilian soccer started in England. While I was at college, my brother arranged a clerical job for me at Macy’s foreign shipping office in London. That was in 1966, the summer that England hosted the World Cup. I had never heard of the World Cup. But now in London it was the only topic of conversation, and I joined in as a way to get my less-than-friendly co-workers to talk to me. After England won the World Cup, British reserve was suspended for two days as fans took over the streets.

WORLD CUP SPECIAL

Italy

Exclusive interview with top player Andrea Pirlo

Spain

How the reigning champions plan to do it again

Argentina

Can Messi ‘the Messiah’ live up to his name?

England

Why are they so bad

at penalties?

Cameroon

The team with ‘hemle’ and Samuel Eto’o on their side

Brazil

One man, a country’s hopes: superstar Neymar

Bosnia & Herzegovina

Their manager talks strategy for their debut World Cup

United States

How the US learnt to

love soccer

Colombia

Can the team affect presidential elections?

How to save a penalty

Dutch goalkeeper

Michel Vorm explains

Brazilian fans had come to England by the thousands, and after defeat, one fan attempted suicide by throwing herself into the Thames. BBC TV showed men and women in Rio de Janeiro weeping, flags lowered to half-mast and mobs burning players and coaches in effigy.

The following summer I joined a student exchange programme in Curitiba in southern Brazil. After I expressed interest in soccer, my host family (Dr Jose Carlos and Eduly Ross) took me to a match, where I was one of about 10 women in the crowd. Those BBC images flooded back, and I had my topic for my term paper, which I eventually extended into a senior-honours thesis.

My thesis showed that the lower-paid players in Curitiba fared better in life than most of their richer counterparts in Rio and São Paulo. The latter spent their big salaries on entourages, or lost it to corrupt money managers, then returned to poverty after playing. In Curitiba, club directors arranged factory or civil-service jobs for their players, who then stayed in the middle class after their careers ended.

Being a novelty, I got an insider’s look at soccer: club directors let me attend their meetings, and took me out drinking afterwards. I heard one talk about bribing a referee, while others described bribing players to throw games. The men either did not take me seriously, or underestimated my improving language skills and drinking capacity. I even got to inaugurate a soccer field at a local country club, where I was presented with a silver plaque inscribed to the “imperialist Yankee sent to spy on Brazilian soccer”.

Eventually I realised my ultimate goal – meeting Pelé. When I arrived in Santos, home of his team, I was warned that he was besieged by interview requests. But he agreed to see me because I was American and female – a combination that had to be seen to be believed. Pelé, then 27, was very polite and helpful.

In 1968, when Pelé came as the guest of the St Louis Stars (playing in the doomed North American Soccer League), I volunteered to serve as his translator. I took him to meet my family, then to see the St Louis arch, and on to a Baskin-Robbins, where he tasted flavours beyond the chocolate, vanilla and strawberry he knew. He was delighted to find a country where he could walk the streets without throngs of fans descending on him.

I started to study Brazilian fans in 1970 at Mexico’s World Cup. Pelé invited me to join the team’s party at their hotel if Brazil won the coveted tri-championship. But the architect Oscar Niemeyer convinced me I’d never get through the crowds, and said I should come to his party instead, as the team had promised to make an appearance (they didn’t). Missing that team celebration is on my shortlist of life’s big regrets.

My book Soccer Madness could not have been written without Pelé’s help. I got funding to go to Rio to research a book in 1972, but women living alone there were suspect then, and no one would rent me an apartment. I was running out of money. I finally met a landlord who agreed to rent to me if I could get a guarantor’s signature. My Brazilian friends’ parents all refused to help.

I prepared to return home in defeat but noticed that the Santos team were playing in Rio. I found Pelé and asked if he would serve as my guarantor. He laughed, saying that no one would believe the signature Edson Arantes do Nascimento (his legal name). Instead he called a friend, personally promising repayment if problems arose. Pelé knew I’d stay to carry out the work that he, too, believed was valuable.

I was trying to demonstrate empirically the paradox of sport: it bonds people while dividing them by the loyalties they hold most dear.

With intra-city club rivalries pitting rich against poor, and the national team tying together Brazilians from all regions, fandom served both pluralism and unity. When I showed photographs to the men I interviewed, more recognised a mid-level local soccer player than Brazil’s finance minister.

The University of Chicago press published Soccer Madness in 1983 to glowing reviews. And I’m still in occasional touch with Pelé. In 2006, he got tickets for me and my niece to see Brazil play Croatia in Berlin at the World Cup. One conversation there, more than anything else, reminded me of the healing energy of sport. A fortysomething German woman explained to me that her generation had always associated her nation’s flag with Nazi atrocities. This was the first time she had ever proudly displayed it.

And my Brazilian family? I remain a cherished member. In 2010, I returned to Curitiba for my “mother’s” 80th birthday.

Janet Lever is the author of ‘Soccer Madness’, available as an eBook from Waveland Press.

To comment on this article please post below, or email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments