Is the UK’s plan to revive ‘left behind’ areas running into trouble?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the market town of Halifax in northern England, a 1980s leisure centre has been boarded up, and encircled by a steel fence.

The site in West Yorkshire should be a hive of construction activity after winning money from the government’s “levelling up” fund for a new gym and swimming pool, but with high inflation adding more than £4mn to the project’s £28mn cost, the local council has reluctantly put the plan on hold.

“It’s a horrible decision to have to make but we’re not the only council that’s going to be in that position,” said Jane Scullion, acting leader of Calderdale council, which covers Halifax. “We couldn’t write a blank cheque.”

Calderdale’s predicament speaks to the government’s increasing difficulty in keeping the Conservatives’ 2019 election pledge to level up “left behind” areas and narrow UK regional inequalities.

It is not just inflation that is undermining projects such as Halifax’s North Bridge leisure centre. The allocation of billions of pounds worth of central government funding for community schemes has slowed after the political chaos that led to the UK having three prime ministers in less than two months.

Local leaders are increasingly questioning how much of the levelling up agenda will ever materialise. Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s Autumn Statement on Thursday is expected to involve a squeeze on capital spending for infrastructure projects, on which much of levelling up relies.

Scullion said part of the problem was inadvertently caused by the government being “in a hurry” to deliver schemes including the revamp of Halifax’s leisure centre, as it looked to provide communities with evidence of improvements by the next election.

The project had been allocated a £12mn grant from the £4.8bn levelling up fund. It was one of nearly 400 schemes to have won funding from that pot and four similar ones: the Towns Fund, the Future High Streets Fund, the UK Community Renewal Fund and the Getting Building Fund.

But such projects are facing multiple headwinds as inflation reaches a 40-year high, supply chains seize up and hundreds of local authorities compete for limited resources in the construction industry. “So we were up against other places, which also had an effect on costs,” said Scallion.

Calderdale council is in contact with civil servants about the future of Halifax’s leisure centre. But after three different levelling up secretaries in just four months, two Whitehall officials said the Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities was in “chaos”.

Only just over a third of the Levelling Up Fund has been allocated, with the second round of distributions running months behind schedule. Jack Shaw, a local government expert at Cambridge university’s Bennett Institute of Public Policy, said just £243mn, or 5 per cent, has actually been spent, according to data obtained under a freedom of information request.

“There’s just loads of problems getting money out the door,” said one government official, adding that the levelling up department was falling behind on spending its budget.

The department said it remained “firmly committed” to all the projects given grants in the first round of the Levelling Up Fund and would be allocating the second batch soon. “We understand the pressures councils are under and are working closely with them to ensure vital public services are protected and levelling up projects delivered,” it added.

The return of Michael Gove as levelling up secretary last month — four months after he was sacked by the then prime minister Boris Johnson — has raised hopes in some quarters that the policy can be put back on track.

“Having Michael Gove back is a good thing,” said Linda Taylor, leader of Cornwall council. “He recognises the fact there needs to be streamlining of how the government gets funding out into the local areas.”

She added that Cornwall had been excited to receive £99mn from the Town Fund and Future High Streets Fund, £14.3mn from the Getting Building Fund and £132mn over three years from the UK Shared Prosperity Fund — the post-Brexit replacement for EU development money.

However she conceded that apart from a small amount of seed funding, the bulk of the money had still not arrived, with Cornwall waiting for Gove’s department to sign off its investment plan in order to access its share of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund.

Taylor said the funding could have a “groundbreaking” impact on the county, which is seeking to grow new industries, including space exploration and mining for critical minerals such as lithium and tungsten.

Still, with so many councils bidding for local improvement projects, business groups warned that the levelling up agenda was failing to underwrite efforts to secure skilled jobs essential to any serious attempt to narrow regional inequalities.

Mark Bretton, national business chair for the Local Enterprise Partnerships, which were started in 2011 to help co-ordinate local government and business development, said the multitude of bidding processes were too “fragmented”.

“That’s not how a business would run its world,” he added. “To have 10 people bidding for the same thing 10 times over is not the way to play it.”

The government’s levelling up funds represent only the “quick wins” of the broader agenda set out eight months ago in Gove’s mammoth 330-page white paper on tackling regional inequalities.

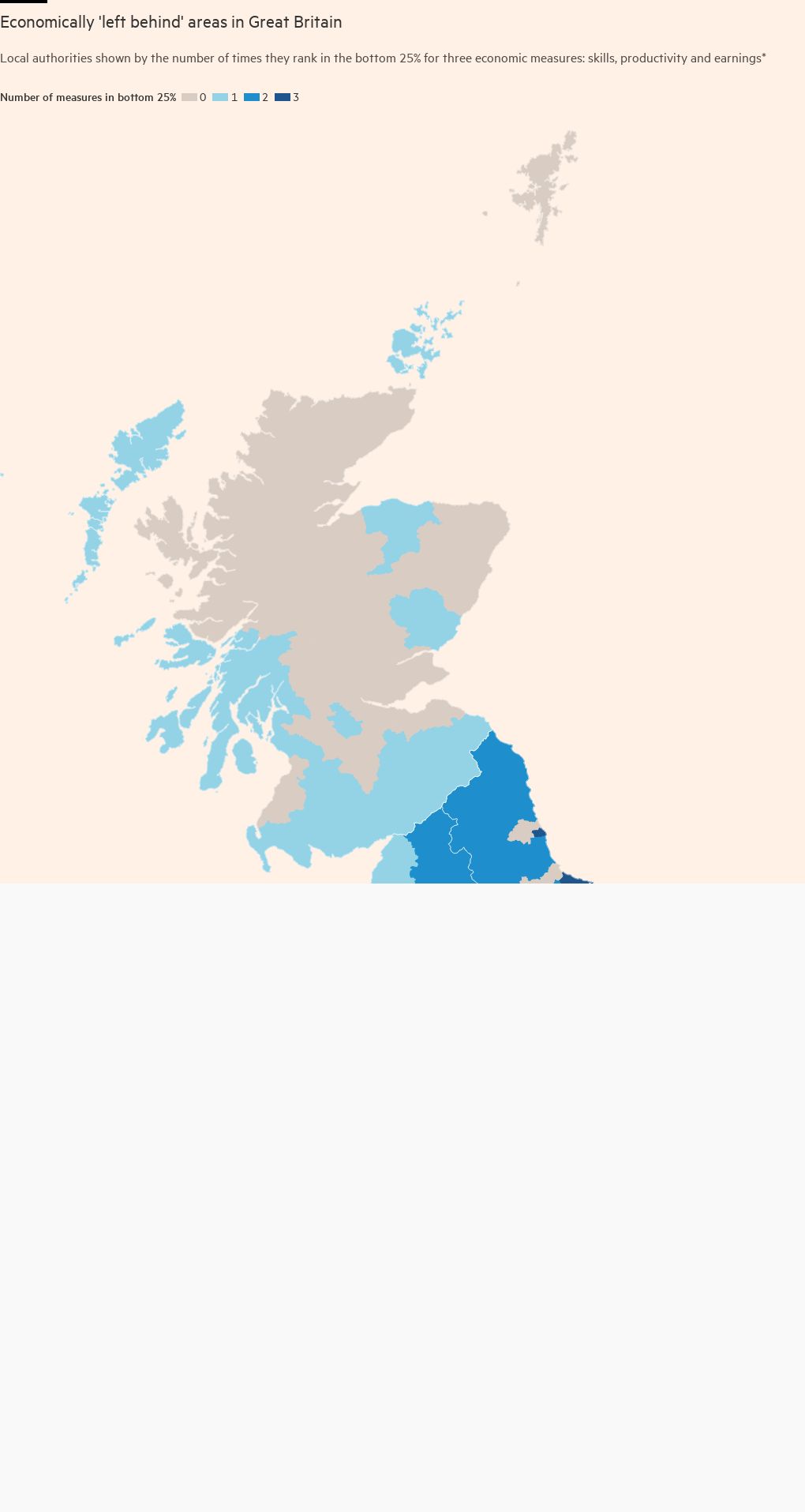

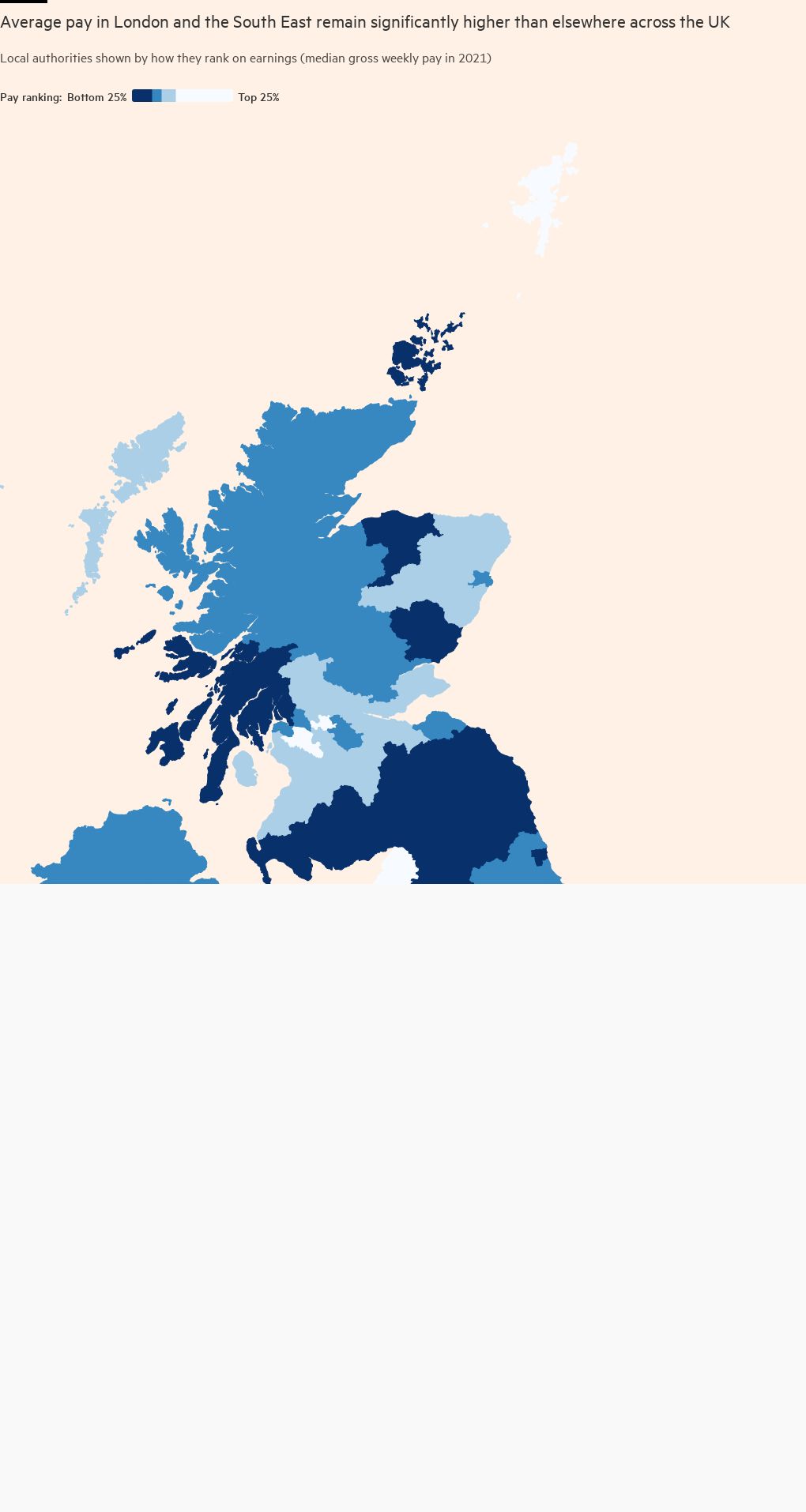

It outlined vast divides in incomes, health, transport infrastructure and research and development spending across the UK, resulting in 12 policy “missions” designed to concentrate the minds of policymakers.

Some progress has been made, with plans for elected mayors in the East Midlands and North Yorkshire to champion their areas finalised over the summer.

The mayors of Greater Manchester and the West Midlands are hoping for enhanced devolution arrangements in the coming months. Cornwall is expecting to conclude a new mayoral deal in 2023.

But plans for 12 levelling up directors to lead on the agenda across the UK’s nations and regions have stalled, after hundreds of candidates applied last spring but none were appointed.

Andrew Carter, head of the Centre for Cities think-tank which focuses on urban regeneration, said the levelling up initiative was now mired in a “general feeling of delay” after a summer of disarray in Whitehall.

“I’m still a believer in levelling up, but while the government is still rhetorically committed, no real progress has been made,” he added. “What we now need from Gove — and sooner rather than later — is to say what bits of that agenda he’s really going to prioritise.”

While waiting for clarity, local government is braced for a fresh round of austerity in Hunt’s Autumn Statement after the spending cuts introduced during the 2010s by the then chancellor George Osborne.

Even some of the architects of the levelling up agenda are starting to doubt it can really deliver. Rachel Wolf, co-author of the 2019 Tory manifesto, said the initiative faced “big challenges” ahead of the next election.

“The only big options available to the government are to pull every non-financial lever they have,” she added, including devolution and moving more R&D funding out of the greater south east of England, as promised.

“But the truth is, it is now going to be very hard to tell the voters who chose Conservative for the first time in 2019 that their lives have improved as a result,” said Wolf.

Comments