Why Britain’s latest Brexit gambit won’t work

This article is an on-site version of our Brexit Briefing newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

Welcome back. Do you work in an industry that has been affected by the UK’s departure from the EU single market and customs union? If so, how is the change hurting — or even benefiting — you and your business? Please keep your feedback coming to brexitbrief@ft.com.

When Lord David Frost announced his latest plan to reboot the Northern Ireland protocol yesterday, he correctly observed that most of the “current friction” between the EU and the UK stems from the rancorous debate over Northern Ireland.

“If we can eliminate this, there is a huge prize on offer,” he wrote in the preamble to the document. “A better and more constructive relationship between the UK and the EU, without mistrust, and working effectively to support joint objectives.”

It’s hard to argue with that statement, and yet it is equally hard to square the substance of the Frost proposals with his gloss that it is all an even-handed, mutually consensual attempt to make the Northern Ireland situation work for both sides.

Because it is plainly not. The 28-page command paper does not offer detailed technical solutions to difficult problems; it is a return to old arguments and an assault on the fundamentals of the protocol itself, which leaves Northern Ireland de facto in the EU single market for goods in order that the rest of the UK could leave the EU on the hardest possible terms.

To make that deal work, Boris Johnson agreed that Northern Ireland should follow large tracts of EU laws and regulations that are set out in the annexes to the protocol. Logically, the enforcement of these rules needs to be under the writ of the European Court of Justice, since that court is the sole arbiter of EU law.

The Frost proposals demand that that structure is replaced with a “treaty-based” approach that uses an international arbitration mechanism.

At the same time, Frost wants UK goods — even if they do not conform to EU standards — to be allowed to circulate freely in Northern Ireland, so long as they are clearly labelled for consumption in the region.

And he wants for companies in Great Britain to be able to self-certify if goods are destined only for Northern Ireland, and if they are, to be exempt from all checks at the Irish Sea border.

For goods going in the other direction (from Northern Ireland into Great Britain) Frost has rejected the EU’s offer of avoiding formal export declarations by using other data sources, such as ship manifests, so that there is no record of goods leaving the EU single market, as is required by EU law.

The ECJ, as the enforcer of the rules of the EU single market would — in Frost’s vision — have no control over goods circulating in Northern Ireland, and no north-south border at which to police them.

The net result of this is a legal free-for-all that removes the border in the Irish Sea and — by inexorable extension — pushes it back either on to the island of Ireland, or into the sea between Ireland and the rest of the EU, thereby diluting Ireland’s place in the EU single market.

Frost is not naive. He knows very well that this proposal will not be acceptable. It is not legally or politically viable. Instead, it is an attempt to rewind the clock back to conceptual arguments that were lost back in 2019, but that the Johnson government now wants to try to win again.

To be fair to Frost, this protocol never looked like his favoured solution. He argued strongly for the “alternative arrangements” to create a light-touch north-south border, believing that the rest of the EU would ultimately force Dublin to accept this compromise.

He was wrong. Merkel and the EU27 held firm and Johnson then agreed the protocol in the space of nine days in October 2019 in order to “get Brexit done”. As we now know from Dominic Cummings’ blog, the prime minister was following instructions to do this and ignore officials “babbling” about Northern Ireland.

Having signed the deal to get Brexit done in 2019, Frost and Johnson then elected to sign a hasty Canada-style trade deal that, by taking the UK as far as possible outside the regulatory orbit of the EU, put the absolute maximum pressure on the Irish Sea border arrangement they agreed the previous year.

These were clear choices, the consequences of which cannot now be cast as unforeseen. Edwin Poots, then the Democratic Unionist party’s agriculture minister, specifically wrote to the government in June last year warning that if it concluded a super-hard EU-UK trade deal without a Swiss-style veterinary agreement to align rules on animal and plant products, the protocol would place “unacceptable burdens” on the people of Northern Ireland.

And so it has come to pass. Six months into the implementation of the protocol, the government clearly regrets those choices and is demanding a rethink based on a mish-mash of pleas to “trust us”, technological solutions and “mutual enforcement” concepts that it knows the EU won’t legally tolerate.

The extraordinary “section one” of the command paper tries to imply that Johnson almost signed the original deal under duress, because (in this telling) parliament’s insistence that the UK could not leave the EU without an agreement had “radically undermined the government’s negotiating hand”.

If that is correct, then by implication the demands in this paper suggest that Frost now believes the Johnson government has a stronger hand created by the deteriorating political and economic facts on the ground, and that he intends to use it.

From an EU perspective this is, as one diplomat described it to me, “gangster politics”. And given the EU is not going to agree to the UK’s core demands, this move seems destined to provoke further EU legal action (which Frosts says is unhelpful) and very likely a UK decision to trigger the Article 16 override clause.

Brexit Briefing

Follow the big issues arising from the UK's separation from the EU. Get Brexit Briefing in your in-box every Thursday. Sign up here.

It is not too late to pull back, but time is short. Businesses want clarity by the end of August on any new rules or extension to grace periods, which Frost has demanded as part of a “standstill” while a new deal is thrashed out.

Perhaps it is still possible, if the EU shows a high degree of flexibility, to keep the core of the protocol but transfer the “at risk” approach that governs tariffs to the agrifood arena, which is by far the largest source of friction. This would instantly reduce the burden of checks.

Still, this latest UK gambit hardly feels conducive to fostering an atmosphere of compromise. Indeed, it will be hard for the European Commission to avoid taking further legal action with regards to the existing agreement, if the UK keeps on this track.

None of this is likely to bring clarity for business or calm to Northern Ireland’s febrile politics. As Frost said, there is indeed a “huge prize” to be had in reaching an agreement. This feels like an odd way to go about grasping it.

Brexit in numbers

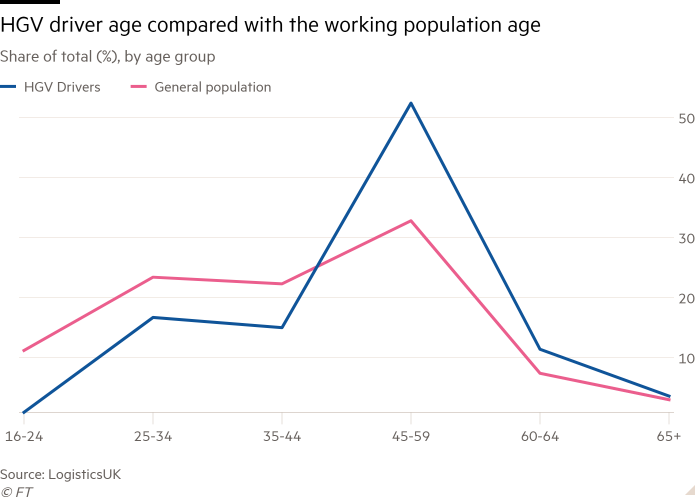

The UK lorry driver shortage, which is estimated at more than 60,000 by the Road Haulage Association, is biting ever harder, and is being further exacerbated by the “pingdemic” of self-isolations caused by the rising Covid-19 case rate.

The haulage industry has been lobbying the government hard for drivers to be put on the visa shortage occupation list, or for the creation of a temporary visa scheme for HGV drivers who are legally too low-skilled to qualify for a visa under the UK’s post-Brexit points-based immigration system.

This week those demands were rebuffed by the government, which instead offered a bunch of half-measures to address the problem. It has pledged to increase the speed of testing for HGV drivers; do more to encourage jobseekers into the profession and raise apprenticeship funding for drivers. It also wants to work with industry to make the profession more attractive by improving lorry park facilities, for example.

All of which is great in the medium term, say haulage industry chiefs, but nowhere near what is needed to address the short-term crisis. As Richard Burnett, the boss of the RHA said, the government proposals don’t “address the critical short-term issues we’re facing. The problem is immediate, and we need to have access to drivers from overseas on short-term visas.”

But ministers are unmoved — or at least the Home Office is unmoved — and in a letter to the industry this week signed jointly by the secretaries of state for transport, the environment and work and pensions, have basically said “sorry, bad luck”.

“We know businesses are under severe pressure at the moment and adapting business models,” they wrote, but add that ultimately “market mechanisms will be the predominant way in which this shortage is resolved”.

This is the political front line of Brexit, which rallied voters to the Leave standard by promising higher wages from curbing EU immigration, but omitted to mention that labour shortages could cause delays and scarcity.

This is a tension that is likely to deepen over the summer.

And, finally, three unmissable Brexit stories

There is a depressing madness about the UK government’s new proposals for post-Brexit trade with Northern Ireland, writes Philip Stephens. Downing Street has made an offer it knows the EU cannot accept. Even where it is inclined to be flexible, Brussels now has confirmation that the UK cannot be trusted to keep its word. The danger is that Northern Ireland will pay the price.

A trade deal based on the notion of “mutual enforcement” or “dual autonomy” would allow the UK and the EU to keep their regulatory autonomy intact, writes former director-general at the European Commission Jonathan Faull. Each would incorporate the legal obligations of the other side into its domestic law, to be applied only by producers exporting goods into the territory of the other party.

Rioting and political turmoil usually turn off investors. But unrest and upheaval in Northern Ireland this year have not stopped the flow of investment into Belfast from financial and professional services firms. US banking giant Citigroup and the Big Four accounting firms PwC, Deloitte and KPMG plan to create thousands of jobs in the city over the next few years. New financial services firms have also dipped into the local talent pool after fDI Intelligence named Belfast the world’s third-biggest fintech centre for the future in a 2019 research report.

Comments