Hollywood says farewell to Chinese investment bonanza

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 2019, Tencent Holdings of China made a savvy call on a future box office smash by agreeing to co-finance Top Gun: Maverick with Skydance, a Hollywood studio.

Tencent had invested in Skydance a year earlier, just one of dozens of deals between Chinese companies and Hollywood studios during the 2010s. But like much of the relationship between China and Hollywood itself, Tencent’s potential Top Gun profits fell victim to great power politics.

Tencent, the world’s largest video games group, pulled out of the investment after executives grew concerned that the Chinese Communist party would be unhappy with its support of a film glorifying the US military. That decision — while a smart domestic political move — cost Tencent a stake in the fifth-best performing film ever in the US. Globally, Top Gun: Maverick has taken more than $1.4bn at the box office since its release in May, and it is still playing in cinemas.

Though it missed out on a cut of the Top Gun earnings, Tencent retains its minority stake in Skydance. It is one of a handful of relationships that remains intact from the 2010s China-Hollywood boom, including Huayi’s investment in AGBO, the production company run by the Russo brothers — the team behind many of Marvel’s biggest superhero hits.

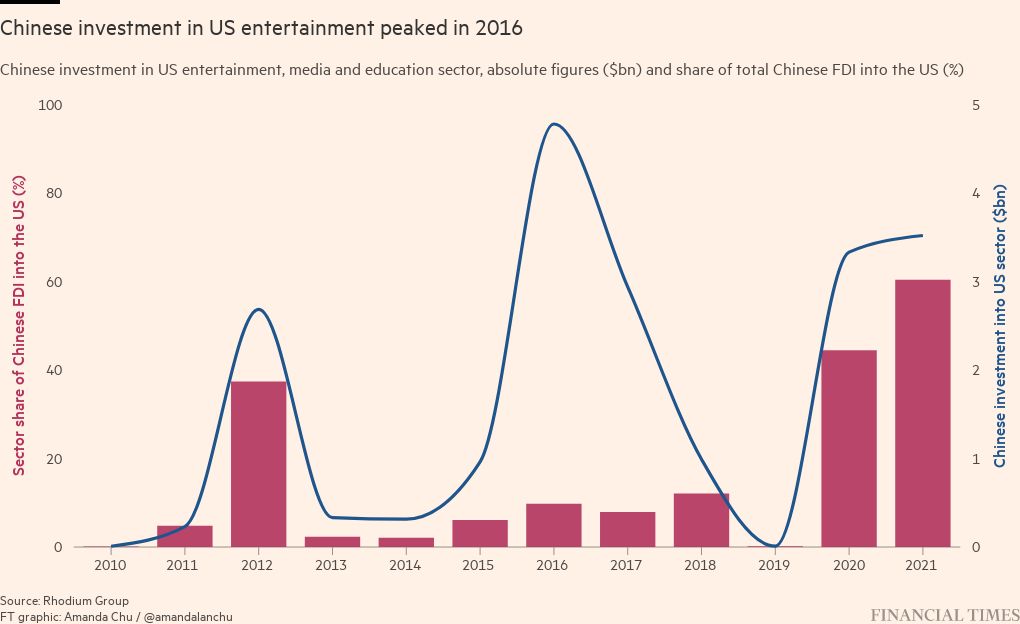

For a while, China’s bold push into Hollywood seemed like good business for both sides. It offered studios an opportunity to tap into a vast, freshly minted middle class in China, where cinemas were being built at breakneck speed. And Chinese companies, flush with cheap capital, were keen to learn the art of moviemaking and help their country develop its own version of soft power. In 2012, Chinese money began to pour into the US media and entertainment sector — about $2.7bn, representing a whopping 37 per cent of China’s total foreign direct investment in the US that year, according to Rhodium Group, a research firm.

“There was a tsunami of both capital and interest coming to Hollywood from China. The deal flow was prodigious,” recalls Stephen Saltzman, head of the international entertainment group at law firm Fieldfisher. “It was a huge boon for Hollywood.”

The peak came in 2016, when Chinese companies invested roughly $4.8bn in US media and entertainment companies, according to Rhodium. Much of that money came from Dalian Wanda, a property and entertainment group that paid $3.5bn for production company Legendary Entertainment. Other significant deals included a $500mn investment by Perfect World in Universal movie slates, and a partnership between Tencent rival Alibaba’s movie business and Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Partners, with Alibaba taking a minority stake and board seat.

Many of the Chinese companies stretched too far, however, attracting unwanted attention from Beijing. Perhaps the most high-profile was Dalian Wanda, which had already paid $2.6bn for the AMC cinema chain in 2012. Wang Jianlin, Wanda’s chair, boldly declared that he wanted to buy one of the big Hollywood studios. (He tried to acquire Paramount but failed.)

Ultimately he became a seller instead of a buyer, shedding a prime property development site in Beverly Hillsand abandoning a bid to buy Dick Clark Productions for $1bn. Last year Wanda sold off its shares in AMC and reduced its ownership of Legendary.

The Chinese buying spree in Hollywood “got out of hand and came to a crashing halt,” says Bennett Pozil, head of corporate banking at East-West Bank, which was an active dealmaker during the period. It never really recovered, he adds.

“There was still some quiet investment in the Trump years, but today it is pretty much non-existent.”

The spending began to slow after Chinese regulators saw the exodus of capital and introduced new rules on “irrational” investments in 2017, which restricted spending in several sectors, including entertainment, says Mark Witzke, senior analyst at Rhodium. “This caused a major fall in outbound FDI in [the entertainment] sector and more broadly,” he says.

Witzke notes that Chinese investment in entertainment rose in 2020-21 but that was almost entirely due to Tencent buying large stakes in Universal Music Group. He adds that the tech crackdown in China makes it unclear whether the group will be as active overseas in future. Recently, company officials said they were looking to pare back Tencent’s investment portfolio.

Geopolitics has also had a chilling effect. Donald Trump’s tough rhetoric and tariffs on Chinese goods after his election as US president in 2016 escalated tensions between the two countries. China’s president Xi Jinping responded by shifting the country’s commercial focus from exports and trade to fostering a more self-reliant economy — including its film industry.

“The soft power initiative has taken a back seat to other priorities of Xi’s administration — which include internal growth, less reliance on US-China relations, and a nationalistic, Maoist perspective,” says Saltzman. “It’s about making sure that domestic Chinese audiences are thinking the same way. It’s a nationalistic [film] product that tends to prevail.”

Pozil says Chinese officials signalled they had learnt everything they needed to know from Hollywood in 2017 following the release of Wolf Warrior 2 — a Rambo-style film featuring a Chinese supersoldier — which grossed more than $850mn. “That was the moment where [China said] ‘We really don’t need you guys,’” he says. “And that was also the theme of the movie too: ‘We really don’t need you. We can do our own stuff.’ That changed things.”

In 2020, China’s box office surpassed North America’s for the first time, albeit at a moment when US cinemas were largely shut down due to Covid-19 restrictions. North America may bounce back this year, since China has been operating under stricter lockdowns. But most experts say the trend clearly favours China becoming the box office leader.

Hollywood films have always faced restrictions in China — whether it meant censoring or altering content, facing caps on the number of films that were allowed in the country during the peak summer months, or limits on the percentage of the box office take they could claim. Still, studios hope for their films to be released in China to boost box office returns — and are often willing to make concessions to gain access to the market.

But now there are questions in Hollywood about how open the Chinese market will be to foreign films once the country’s Covid lockdowns lift. Two recent blockbuster films in the west, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness and Spider-Man: No Way Home were blocked in China for obscure reasons. (It was reported that Chinese censors were opposed to an action scene in Spider-Man that takes place on the Statue of Liberty.)

Saltzman believes China will probably need Hollywood movies when its Covid restrictions ease, even if regulators continue to promote local films over imports.

“They’re going to want to make sure the industry can thrive and that theatres are full again,” he says. “It’s going to be very carefully orchestrated and calculated. And it’s going to benefit the big [US] studios more than anyone else because it’s going to be the big tent-pole [films] that they feel are politically safe.”

Comments