From ‘catastrophic’ health spending to universal coverage

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

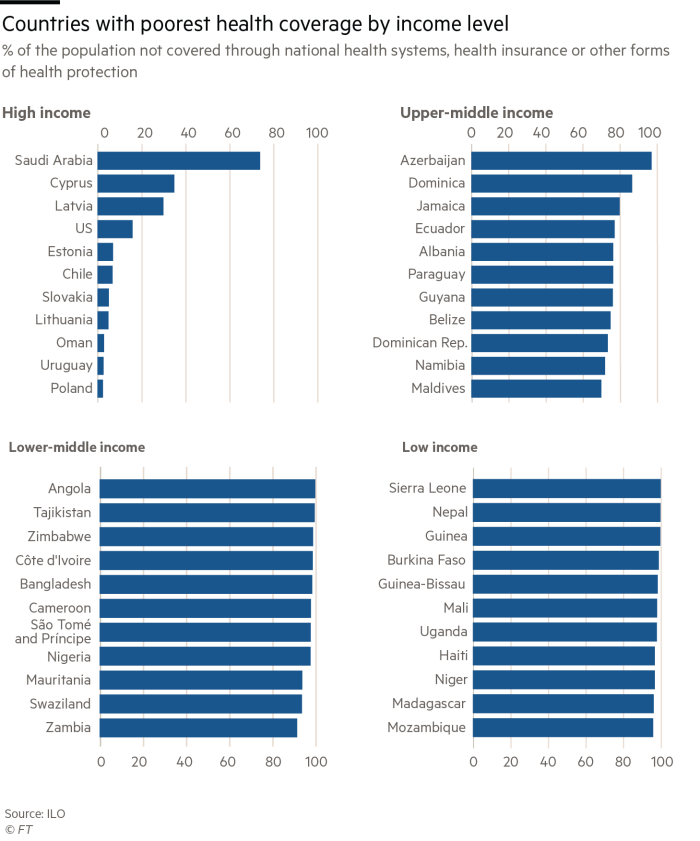

Access to healthcare has become a central issue in the race to become Democratic candidate for US president. The world’s largest economy has the highest healthcare costs in the developed world, yet 16 per cent of its population does not have health coverage through an insurance scheme.

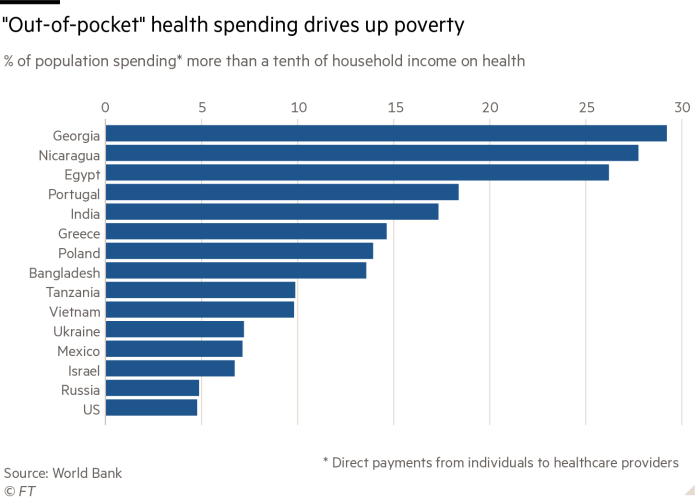

Data from 2015 suggest nearly one in 20 Americans were paying for healthcare “out of pocket”, spending nearly a tenth of their income to get treatment without reimbursement.

This is an example of what international organisations call “catastrophic” health spending. In Georgia, for example, out-of-pocket spending affects nearly 30 per cent of the population.

Some 800m people around the world spend more than 10 per cent of their income each year on healthcare and nearly 100m people are pushed into extreme poverty by these expenses.

Personal spending accounts for 40 to 50 per cent of health expenditure in low- and middle-income countries, compared with 30 per cent in their richer counterparts.

Universal health coverage is based on the idea that everyone should have access to affordable healthcare. It is not the same thing as free — or rather, government-funded — healthcare. The World Health Organization describes it as a situation where “everyone is able to use the quality health services they need without experiencing financial hardship”.

Representatives of world governments at September’s UN high-level meeting pledged to invest in four key areas of primary care as part of a strategy to double universal health coverage by 2030.

It is the most comprehensive and high-level political agreement of its kind — and comes some 135 years after Germany became the first country to move towards a version of healthcare coverage for all.

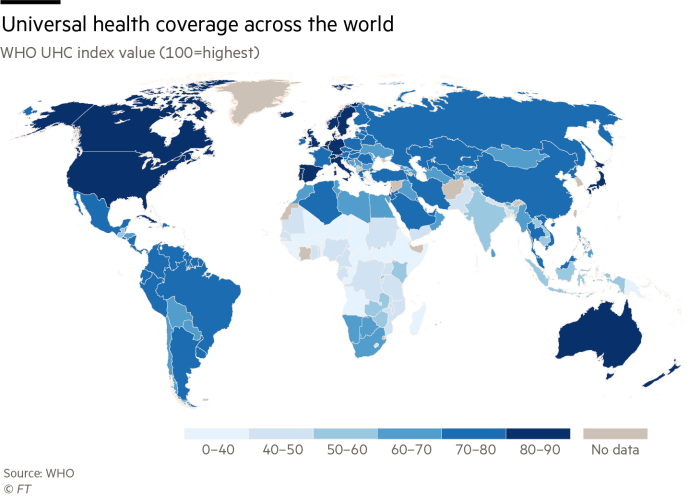

The WHO monitors the progress of universal health coverage across the world. Its UHC index assigns a score to each country based on services provided and whether citizens suffer undue financial hardship as a result. The index runs from 0 to 100 with high-performing countries scoring above 75 and low-performers scoring below 60.

“Universal health coverage is a political choice,” says Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, yet the arguments for it are also economic.

In countries such as Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania, extreme poverty and poor local healthcare arrangements hinder the development of a universal system.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the former Nigerian finance minister, said: “A healthy infant does not need medical treatment or care, both of which come at a cost. She also has a greater chance of growing into a healthier child, able to attend school and ultimately become a more productive member of society. And instead of caring for a sick child, her parents are in a better position to go out to work and increase their own ability to earn, which means they will have a greater disposable income to feed back into the economy.”

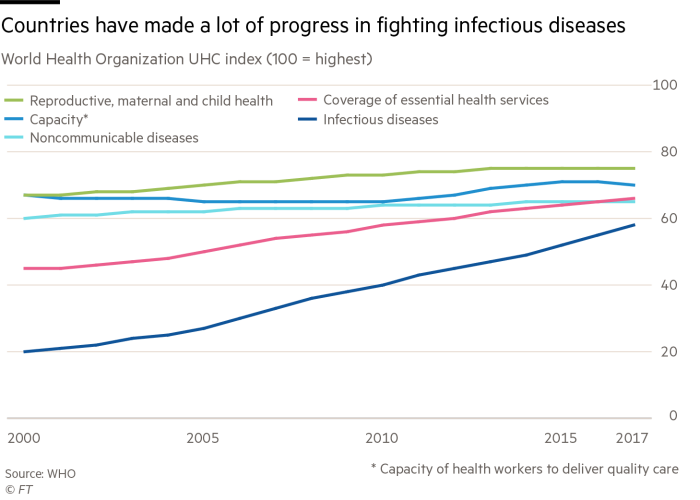

Some initiatives such as vaccination programmes bring obvious results. Research published in Health Affairs journal found that for every dollar invested in childhood immunisation, $16 could be saved in healthcare costs and lost wages and productivity as children grow into adults.

In some ways, African countries are ahead of the pack when it comes to universal health coverage. Rwanda has recently extended health insurance to 90 per cent of its population through a scheme called Mutuelle de Santé, which has been credited with lowering the country’s maternal and infant mortality rates by 77 per cent and 70 per cent respectively since 2000.

President Paul Kagame told world leaders gathered at the UN that the scheme showed “that it is possible for countries at every income level to make healthcare affordable and accessible for all”.

Meanwhile, in the US alone, as many as 45,000 deaths a year are linked to a lack of health insurance, according to a 2009 study published in the American Journal of Public Health. Globally, the lack of access to adequate healthcare results in a woman or baby dying every 11 seconds during childbirth.

Since 2015, treatment offered through universal health coverage has improved in 138 countries out of 183 monitored by the WHO. However, it has worsened in 18.

One of those in which it is improving is the Philippines. In February, Rodrigo Duterte, the country’s president, signed a universal healthcare law, which will automatically enrol every citizen in a newly created national health insurance programme.

Melinda Gates, co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation — a body that funds health, development and educational causes — welcomed the pledge by global leaders to invest in expanding universal healthcare coverage.

“Now that the world has committed to health for all, it is time to get down to the hard work of turning those commitments into results,” she said.

Comments