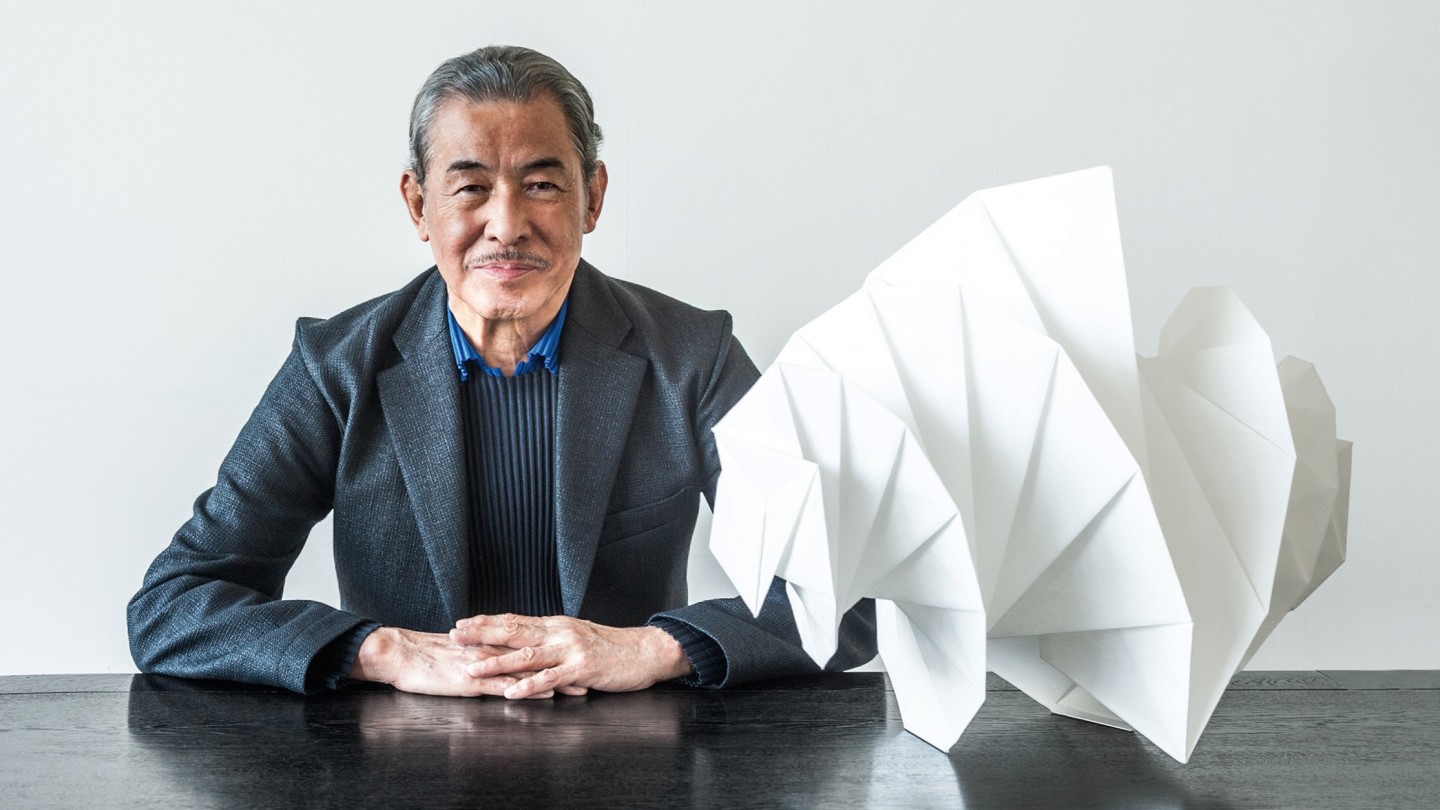

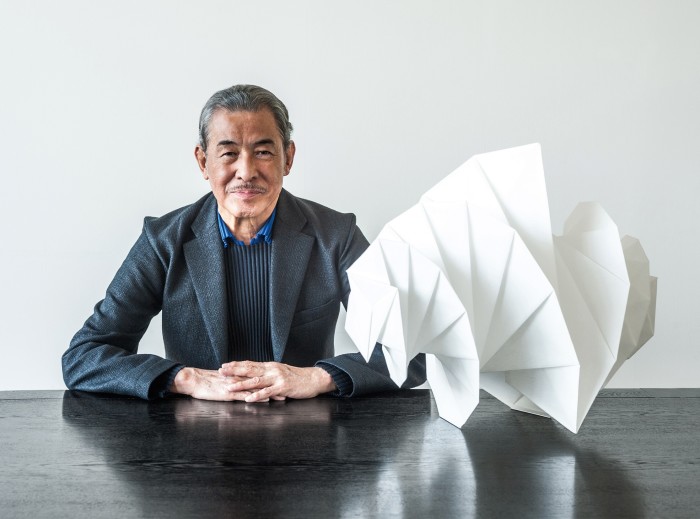

Issey Miyake: a truly modern icon

Simply sign up to the Fashion myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Some label him an artist, others see him as a style visionary, but more than anything else, Issey Miyake is the designer’s designer. For more than four decades he has created textiles, clothing and accessories for people who embrace contemporary visual culture, but who find the notion of “fashion” at least slightly ludicrous. People, in fact, such as him. Sitting in a glass-walled corner room of his Shibuya design studio overlooking Yoyogi Park, and surrounded by immaculate postmodern vintage furniture by his late friend and collaborator Shiro Kuramata, he explains his credo. “I prefer the term ‘making things’,” he says. “I want to represent the action of thinking. We are working towards the concept of […] no fashion.”

Miyake has never been busier “making things”. In the past two years he has launched a wealth of new clothing, fragrance, accessory and interiors lines, and has been campaigning for the creation of Japan’s first major design museum. At the same time, his studio enjoys the same credibility in the design world as the star architects who wear what comes out of it. With every decade, the studio has become more technically ambitious, producing garments that often transcend gender and flatter every body shape through elasticity and structure. As architect Tadao Ando, who has known Miyake since 1972 and designed his 21_21 Design Sight public gallery and “research space” in Tokyo, says: “He has tirelessly persisted in exploring the possibilities of a single piece of cloth.” More than that, he has created clothes that people enjoy wearing beyond their aesthetic appeal. His work can be sculptural and clever, but it is also comfortable and empowering. “He’s a brilliant man,” says Zaha Hadid, who buys regularly from his mainline collection. “The clothes are versatile and you can travel with them everywhere. When they are on show in the shop it’s one thing, but once you wear them, they become something else. They are animated.”

While many of his peers present collections that are alternately sepulchral for spring and funereal for autumn, Miyake is a sunbeam of irreverent energy – his presentations are full of laughter, dance and joie de vivre. As are the clothes: this season’s dynamic, brightly coloured Ray Stripe Dress (£365) from the Pleats Please Issey Miyake label would be as at home on a Caribbean beach as it would at a gallery opening. He may be a serious aesthete, but his sense of fun and curiosity led him to the dancefloor of Studio 54 with Diana Vreeland, and to give over the inaugural exhibition at 21_21 Design Sight to objects inspired by chocolate. Endearingly, his favourite word to employ when describing what he considers his most successful work is “amusing”. “All I want,” he says, “is for people to experience a sense of joy when they wear my clothes.”

Unlike many conceptual designers who have attempted to carve a niche in apparel, the wearable nature of Miyake’s designs has resulted in a business that is as commercial as it is creative – and that remains independently owned. In 2012, a Pleats Please Issey Miyake fragrance (£46 for 50ml) was launched to join the existing stable of five globally successful perfumes (a bottle of L’Eau d’Issey is sold every five minutes somewhere in the world, and a bottle of L’Eau d’Issey Pour Homme every seven minutes), while the neat, folding, sci-fi geometry of the bags in the Bao Bao line (from £295) has made them a bestseller in myriad colourways and finishes. At the end of last year he opened a new flagship store in Tokyo, named after his Reality Lab studio-within-a-studio and stocking his innovative 132 5. Issey Miyake collections for men and women and a brand-new menswear line, Homme Plissé Issey Miyake. He was, he says, responding to demand: “I discovered that around 10 per cent of Pleats Please was being bought by men.” Hence the new, similarly pleated range – essentially, technologically advanced sportswear.

The new men’s line was first seen in a spectacularly choreographed performance by the Aomori University Men’s Rhythmic Gymnastics team last July (Miyake was keen to support the team, who are from a region that was badly affected by the 2011 earthquake), but it would be equally suited, in basic black, to businessmen flying long-haul, looking for something comfortable, chic and durable. “The clothes are relaxing and not too tight. It’s really important that they are worn – and not just for sports,” says Miyake. “They can work in an office environment.” Indeed, Steve Jobs – the very definition of the media professional – wore Miyake black polo-neck jumpers for more than two decades. And though there are always flights of futurist fantasy, the Issey Miyake Men label is a good port of call for meticulous but relaxed tailoring (such as this season’s Barathea jacket, £1,320) or a stylish, restrained pair of Side-Gore trainers (£425), while the more experimental 132 5. Issey Miyake line includes voluminous, practical raincoats (£735) made from recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET), used in plastic bottles.

The hub of Miyake’s empire is the Reality Lab department at the Miyake Design Studio. This is where his small team – including textile engineer Manabu Kikuchi, pattern engineer Sachiko Yamamoto and employees who have been working with him since before the Issey Miyake brand launched in 1971 – articulate designs for the 132 5. collection that often have their basis in complex computer-generated 3D shapes by Jun Mitani, associate professor at the Department of Computer Science, Tsukuba University. 132 5. is one part origami, two parts advanced mathematics; the result includes the new Grid cardigan (£645) and skirt (£425) with triangular panels of grey, blue and green. For the 132 5. spring collection, dynamic helix shapes, originally developed by scientists for solar panels orbiting the earth, have been reworked into flat patterns and garments. The process is both difficult and extraordinary – two things that clearly excite Miyake, for whom the journey of creation is as stimulating as the end result.

Miyake’s work is celebrated industry-wide, not only for its use of the most advanced technology available (132 5. won The Design of the Year Award in the fashion category at the Design Museum Awards in 2012), but also for its handcrafted components. He continues to patronise the washi paper-makers of Tohoku for some of his most rarefied textiles, while some elements of their traditional craft are echoed in the industrial production of textiles from recycled PET bottles, currently used for his IN-EI lights, developed with Artemide (such as the Mendori light, £635, and the Minomushi Terra floor light, £1,380). One inspires the other. “We need both elements,” he says. “If we lose handcraft work, then we will ultimately see a future where no new technology is created, either.”

Designer Ron Arad has been a fan of Miyake’s work since the 1980s and collaborated with him and Miyake’s then design partner, Dai Fujiwara, on his Ripple Chair project in 2006. He believes that it is Miyake’s embrace of technology that makes him so significant. “The computer is as much a tool as scissors,” says Arad. “And it doesn’t matter how good the synthesiser is – it’s how good the musician is. You need to know how to accept and consume technology.”

In addition to Miyake’s own definitive private archive in Tokyo, his work is in the permanent collections of the V&A in London, MoMa in New York and key museums worldwide. Item 11728 at the Kyoto Costume Institute is Miyake’s 1982 Samurai rattan armour; as well as the label “fashion”, Miyake has repeatedly shrugged off the definition “Japanese designer”, although some of his early 1970s and 1980s work exaggerates and distorts the construction of the traditional kimono. There are 192 Miyake pieces at the Institute – some more “Japanese” than others. The Institute’s director and chief curator, Akiko Fukai, believes that the 2D aspects of his clothing are most significant. “It’s a very abstract aesthetic,” she says. “When the Japanese start to make clothes, they always think flat; they don’t work on the human body. Miyake has always tried to make clothes that are cosmopolitan, but they still start flat.”

To illustrate her point, she shows a collection of items; the outline of each garment is perforated into one single piece of knit tube, ready for cutting by the wearer. These are samples of the work that Miyake produced with Fujiwara as part of their A-POC label, launched in 2000, elements of which developed into what is now A-POC Inside. Like much of Miyake’s Pleats Please work, and the 132 5. range, it is appealingly graphic when its fabric is spread horizontally – something photographer Irving Penn appreciated in his iconic images of Miyake’s work, in which the models’ legs and arms are out-thrust, emerging from dramatic, billowing fabric.

“A-POC was the most exciting thing that has happened in industrial design,” says Arad. “The more sophisticated a machine gets, the less machine-like the product is. And that sums up A-POC for me.” The concept was ingenious but challenging – garments were “finished” by the client. Final lengths were determined by cutting along lines in the cloth. “You attack the fabric with scissors and it doesn’t fray,” says Arad. “It’s amazing. It’s the sort of thing that could only come from Miyake and his collaborators.” While the current A-POC Inside label now offers ready-to-wear garments, many pieces still incorporate original A-POC techniques, with demarcation lines for customers to cut and shorten themselves.

Along with the vertical integration of his company, it’s Miyake’s enthusiasm for collaboration that has given him his edge. His career began in the 1960s with spells working at Guy Laroche and Givenchy in Paris and with Geoffrey Beene in New York. “I was a foreigner, trying to represent myself,” he says. “I looked at the designers in Paris and they were so sophisticated, with such high-quality engineering. I wondered how I could surpass that. I came back to Tokyo and looked for textile designers, pattern-cutters and people who could use great technology.” When Miyake talks about his studio now, it is as a collective.

Yoshiyuki Miyamae and Yusuke Takahashi currently design the mainline Issey Miyake and Issey Miyake Men labels respectively, while Takahashi remains part of the Reality Lab team. Miyamae focuses on channelling the “intelligence, cheerfulness and inner beauty” of the womenswear that he believes are in the Miyake DNA, while for this spring Takahashi’s menswear is concerned with traditional dyeing techniques. “I’ve tried to express a pop and fun aspect,” he says. “At the same time, I am working with factories that have collaborated with Mr Miyake for years. And I always ask myself – is a certain design the most effective way of showing a textile’s potential? And is the idea new and fun as well as having masculine strengths and qualities?” The new season’s Wrinkle shirts (£395) resemble colourfully pixellated Seurat canvases, while a batik coat (£1,425), shirt (£750) and matching denim trousers (£530) suggest the energy of Jackson Pollock.

Before any collection makes it to Paris, everything is presented to Miyake himself at the studio’s somi (“general see”). Changes are sometimes made, but Miyake’s guiding hand is gentle and generous. “I always tell them that they don’t need me,” he says. “But I have to make sure that there is a concept with universal appeal. The work isn’t complete unless someone wears it. Also, I consider the somi a process of studying and learning – for myself. It’s crucial that the designers are establishing their own ideas.”

One particularly successful ongoing collaborative project at the Miyake studio is the line of watches – first launched in 2001 with a timepiece designed by Shunji Yamanaka, and now with a permanent collection of 13 different styles by the likes of designer Ross Lovegrove and artist Tokujin Yoshioka. The choice of designers is significant. “They are all in line with Miyake’s way of thinking: they are all looking to the future,” says Midori Kitamura, president of the Miyake Design Studio. “And all our collaborators are very established – they don’t need our support. They want to work with us.” The latest watch, released last year, is the Please Issey Miyake (£199) by Jasper Morrison, who was inspired to create a pleated surround for his timepiece after seeing one of Irving Penn’s photographs of a Miyake garment. “I was so impressed by the way Penn captured the Issey Miyake design spirit that I thought I should do the same,” he says. “The Miyake aesthetic is defined by a great eye for line and volume.”

When Miyake talks about inspiration, he frequently mentions the installation artist Christo and the ceramicist Lucie Rie, whom he used to visit after showing in Paris each season to “come back to basics, or, as we say in Japanese, ‘wash my eyes’”. But of all the figures who have influenced him, designer and sculptor Isamu Noguchi is the most revered.

There are superficial similarities between Noguchi’s iconic lanterns and Miyake’s IN-EI lights, but Miyake’s work – created applying the same mathematical theories of 3D design as in his 132 5. collection – has a significantly different structure.

The PET re-treated fibre light starts flat, then unfolds and clicks into shape without any inner frame. More than his own concerns with form and an enchantment with light and shadow, Noguchi’s creative approach and notion of identity have shaped Miyake’s work for decades – from his childhood when he became fascinated by the Noguchi-designed bridge that he had to cross to get to school in Hiroshima every morning, to the later years they spent together as friends.

“I remember living in Paris in the 1960s,” says Miyake. “I looked in the mirror and saw some funny-looking guy reflected back at me and wondered, ‘How can I live here, as one of the few Japanese men in France?’” That same day, Miyake happened upon one of Noguchi’s now-iconic round pendant lights in a store in Saint-Germain and had a revelation about the global nature of design and identity. “I knew all about Noguchi,” he recalls. “He was born in the United States and was trying to identify as Japanese, while I was the opposite – Japanese and trying to live globally. I realised right then that I needed to transcend the idea of being ‘Japanese’. Noguchi’s creations didn’t need any adjective. Today, I think I do represent some kind of Japanese aesthetic and beauty, but I have never bettered Noguchi’s work. He is pure light. Maybe I am the shadow.”

Issey Miyake, 52 Conduit Street, London W1 (020-7851 4620). Pleats Please Issey Miyake, 20 Brook Street, London W1 (020-7495 2306). Reality Lab, 1F, 5-3-10 Minami Aoyama Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-0062 (+813-3349 96476). isseymiyake.com.

Comments