ESG bond funds held back by fear of criticising US, research suggests

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Interested in ETFs?

Visit our ETF Hub for investor news and education, market updates and analysis and easy-to-use tools to help you select the right ETFs.

Fund managers’ unwillingness to criticise western governments, particularly that of the US, is holding back the development of “sustainable” government bond funds, research suggests.

While corporate bonds can be scored using a similar ESG scoring system to that used for equities, “there are still question marks over how to best evaluate government debt, where there is a fine line between making an objective ESG assessment and straying into political territory”, said Kenneth Lamont, research analyst for passive strategies at Morningstar.

“Taking a stand against the policies of an elected government, even if rationalised from an ESG perspective, is something that individual investors may find easy to do. However, large asset managers or ESG-rating companies risk being accused of unduly interfering with a political process,” he added.

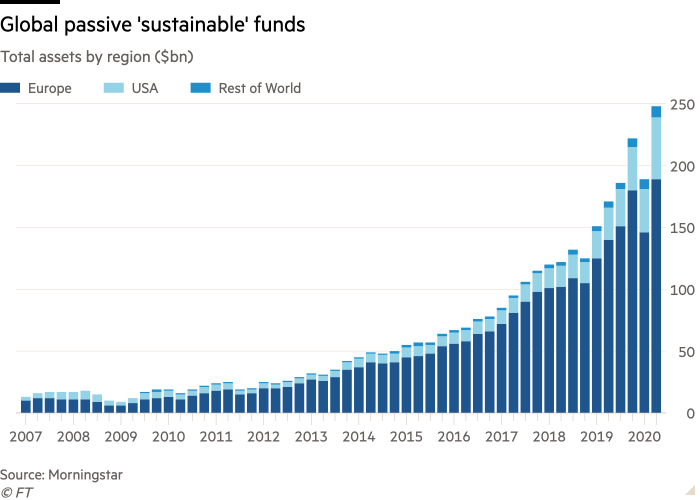

Passive ESG funds, which incorporate environmental, social and governance concerns, have seen huge inflows in the past 18 months, with assets doubling $250bn, according to data from Morningstar.

However, Morningstar said that the rollout of passive ESG bond funds remained “embryonic” compared to that of equities, with the sector held back by the “challenges of assigning ESG ratings to government debt”.

The debate about evaluating sovereign debt issuers may be most acute around the US, which some could say fails to meet the necessary ESG standards, yet is by far the largest issuer of debt, accounting for 36 per cent of the FTSE World Government Bond Index.

“At what point do you exclude the US?” asked Mr Lamont. “It is the biggest arms manufacturer in the world, you have social inequality. It is one of the biggest polluters and withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement, and yet excluding the US from your fixed income exposure is problematic.”

He said some fund groups had “admitted that if they were to strictly follow their ESG guidelines the US would be excluded”, but for investment reasons decided that they cannot ignore the “largest and safest” government bond market in the world.

Mr Lamont said this was less a case of “cowardice” on the part of fund providers, but rather one of “pragmatism”.

“It’s quite a tricky issue how we rate government debt on its ESG credentials,” he added. “We haven’t reached anything like a consensus on how this should be approached. It’s about having a framework that makes sense. It isn’t about annoying the US.”

Morningstar also said operating an ESG model for developed-world debt was difficult because advanced countries tended to share many similarities, lacking the wide dispersion in macroeconomic conditions and risk/return profiles witnessed in emerging markets.

Yet even in emerging markets ESG-based sovereign bond investment can be problematic. Morningstar said that ESG assessments tended to be based on social and macroeconomic indicators, such as data on labour markets, educational standards and social mobility.

This means middle-income developing countries such as Poland, Chile and the Czech Republic are rated more highly than the likes of Bangladesh, Nigeria and Ivory Coast.

ESG investing therefore risks starving the countries arguably most in need of funding and instead lending more to those that already have better access to markets, unless the ESG rating is explicitly adjusted for each country’s level of development.

“The link between ESG scores and per capita GDP is strong. How can you reconcile a focus on ESG principles with investments in emerging and frontier markets that are, almost by definition, less well governed, more corrupt and increasingly more polluted than developed markets?” said Charles Robertson, chief economist at Renaissance Capital, an emerging markets-focused consultancy.

As a result, and despite the relative ease of operating an ESG approach to corporate bonds, fixed income funds account for just 9 per cent of passively managed “sustainable” money. In comparison, bond funds constitute 22 per cent of mainstream “non-sustainable” passive investment.

European investors have just 53 passive fixed income funds to choose from, Morningstar found, while there are only 12 aimed at US investors, out of the 534 “sustainable” index-tracking funds available globally across all asset classes.

As a result, fixed income funds have largely missed out on the recent sharp inflows into passive ESG.

However Amin Rajan, founder of Create Research, a consultancy, argued that there was simply a lack of interest among institutional investors in government bonds at the moment, due to yields being at record lows and the perception that sovereign debt no longer provides the same diversification benefits that it once did.

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

Comments