Collector Suzanne McFayden: ‘Buying art is a way of collecting different pieces of me’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“Buying art is a way of collecting different pieces of me!” So says the Texas- and New York-based art lover Suzanne McFayden. “I include things seminal to my life and to who I am, but also to the histories of people who have been marginalised in one way or another.”

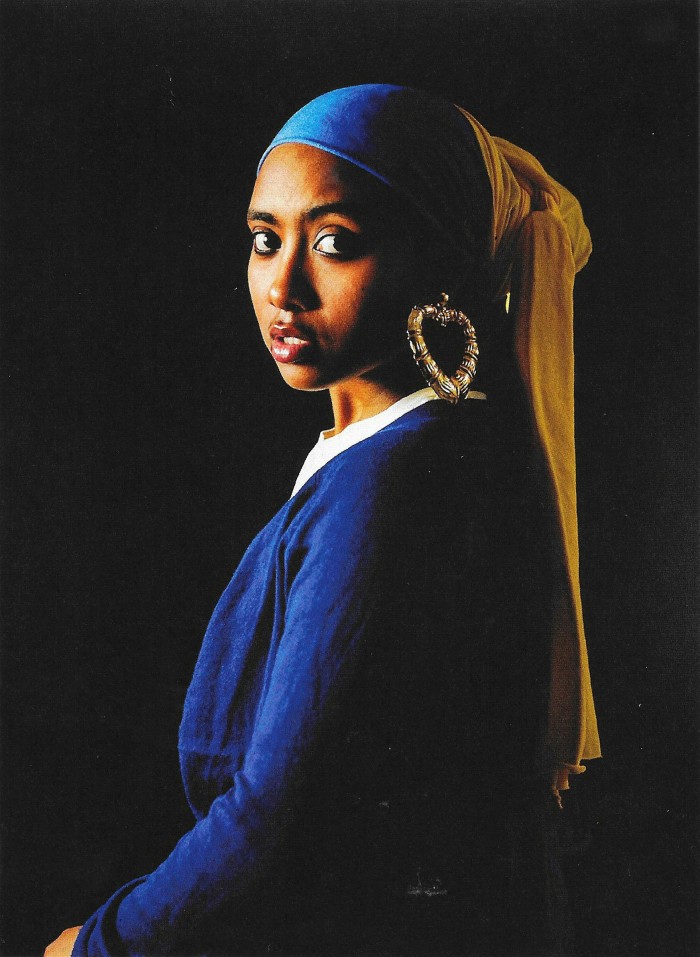

Reflecting her heritage as a Jamaican-born, US-based black woman, those “different pieces of me” include Hiroshi Sugimoto’s “Caribbean Sea” (1980); Glenn Ligon’s “Silver Self-Portrait #1” (2005); Tracey Emin’s neon “Trust Yourself” (2012); Awol Erizku’s “Girl With a Bamboo Earring” (2009); an untitled wire sculpture by Ruth Asawa from about 1960; and Nari Ward’s shoelace work “FIRE!!” (2019). While McFayden’s focus tends to be on black artists, this is not exclusive. And as a woman who is proud of having spent 25 years as a mother and homemaker, she also embraces pieces such as Sheila Hicks’ cotton and muslin rope piece “Cord Structure” (1976).

McFayden is talking to me over Zoom from her New York home where she is spending the spring break with her three children, now college-age. While Austin, Texas, remains her base, she is heavily involved with the Studio Museum in Harlem, where she is a board member, and she is soon to become board chair at her local Blanton Museum of Art.

Nothing in her background could have prepared her for the life she now leads. She was raised by a modest family in Jamaica, and her first encounter with art came when her father bought an edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica from a travelling salesman — “So I and my five siblings could learn about the world; and all but one went on to university,” she says. The entries about travel and art fascinated her the most. Then, on a trip to the UK, her mother bought a reproduction of a Turner landscape from the Tate gallery, and it was given pride of place in the family home.

Studious and bookish, McFayden gained a full scholarship to the prestigious Cornell University in the US to study French literature, where she met her now ex-husband, Robert Smith. He is the billionaire philanthropist who paid off the student debt of an entire college class in 2019, but who also settled a $140m tax investigation last year. They divorced in 2010.

After her marriage to Smith ended, McFayden lived for a time in Switzerland and visited Art Basel where she saw a Basquiat painting — “a bright sheet of red, with a gold crown in the middle” — and a Glenn Ligon work from the Stranger in the Village series, based on the novelist James Baldwin’s essays recounting his experience as the first African American to visit a small town in Switzerland. “My mind just exploded! I’m still getting a chill, just talking about it right now,” she says. She started buying art at that point, but really dates her collecting to about five years ago. “That’s when I began to think more about what I was doing, what focus I wanted to have,” she says.

This was connected to her own experiences. “I did struggle at Cornell at the beginning,” she admits. “I came from a nation that was 97 per cent black, when I first got to America I didn’t understand the race thing — yet. But later on, I began to see the clear disparity between people of colour and non-people of colour. And I noticed who got promotions, who was [part of] the ‘in’ club.”

She cites incidents, after she had children, such as white girls in her daughters’ very progressive Californian school touching their hair because of its texture. Even more crucial was her terror as her children started driving, about which she wrote an article in the New York Times, “Teaching My Kids to Drive While Black”. “I had taught my children to be proud of their heritage, never to be ashamed of their blackness,” she says, but at the same time she feared that advocating for themselves could have fatal consequences if they were stopped by the police. “The inclination is to shoot first and ask questions later,” she laments.

We are talking while what she calls the “ultimate terrible spectre” of the George Floyd trial is under way in a Minneapolis courtroom. And yet her choices in art are, she says, driven by joy. For example, she has a brightly coloured 2017 work by Yinka Shonibare, “The American Library Collection (Designers)”, and she loves the wind sculptures he installed in Central Park. “Our people have been blown to all corners of the world,” she says. “We have no common language, since we don’t know if we come from Benin, Nigeria or elsewhere, so I am a big believer in supporting artists’ shows. We need to show that there is a history of black artists’ work, just as there is one for other artists.”

Among the shows she has supported are Mark Bradford’s End Papers at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and Julie Mehretu’s mid-career survey currently on view at the Whitney Museum. But she has not been drawn into the current frenzy about some emerging black artists “whose prices have gone from $20,000 to $4m in a year. I am more interested in looking at marginalised voices, often those of women artists,” she says.

“So many were left out, and yet they deserve to be in that equation. As a collector, I want to claim the space that they were so long denied.” And she admires Theaster Gates — an artist she doesn’t own — for saying that black people must make their art regardless of the “white gaze” on them.

McFayden is excited by the choice of sculptor Simone Leigh as the United States’ entry for next year’s Venice Biennale. “She has been toiling away in the space of black feminists, this choice is honouring the art history of black women,” says McFayden. “For so long, black women have been the nannies, the cooks, they supported the infrastructure of people going to Wall Street. This is the time to acknowledge the people without whom a lot of this wealth could not be made.”

How do her children, now grown, react to her art collecting? “Sometimes they are horrified by my choices,” she answers. “For instance, my daughter didn’t understand an Alma Thomas I have. And I have a work by Wangechi Mutu, ‘I Have Peg Leg Nightmares’ (2003), a collage work on paper — I had it at the entry to my home, I found it so lyrical and moving, and she said it made her afraid. But that’s good as well, because you get to have a conversation about it.”

But sometimes her children push her as well. On visiting the retrospective by the British-Guyanese artist Frank Bowling at the Tate in 2019, one of her daughters exclaimed “Mom, Mom, you have to have one!” She had fallen in love with the vibrant colours, the pinks and yellows . . . and “Mom” did indeed buy a work. McFayden now laughs when she recalls her own reaction to that Turner landscape all those years ago: “I thought it was so boring, but my mother loved it — so all power to her!”

Comments