How Islamic art inspired Cartier’s era-defining Art Deco pieces

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Almost a century after the Art Deco style took the world by storm, collectors are still willing to pay a premium for pieces from that era. Jewellery houses will also often refer back to their archives to design contemporary pieces that pander to high jewellery buyers’ desire for the Art Deco aesthetic.

And for French jeweller Louis Cartier, it was a passion for Islamic art that was behind some of the most defining Art Deco pieces of the 1920s and 1930s.

“The shapes, the patterns, motifs and the juxtaposition of colours that define [the] Art Deco period for Cartier would not have been possible without the influence of Islamic art,” says Pierre Rainero, director of image, style and heritage at Cartier today.

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris has just opened an exhibition on the very subject, in collaboration with the Dallas Museum of Art and the Louvre. It features more than 500 pieces, including masterpieces of Islamic art, drawings, photographs, archival documents, objects and jewellery by Cartier which trace the origin of Islamic influence from the 1920s until the present day.

At the beginning of the 1900s, Paris was home to a fledgling Islamic art market for which Louis Cartier, grandson of founder Louis-François Cartier, developed a strong sensibility.

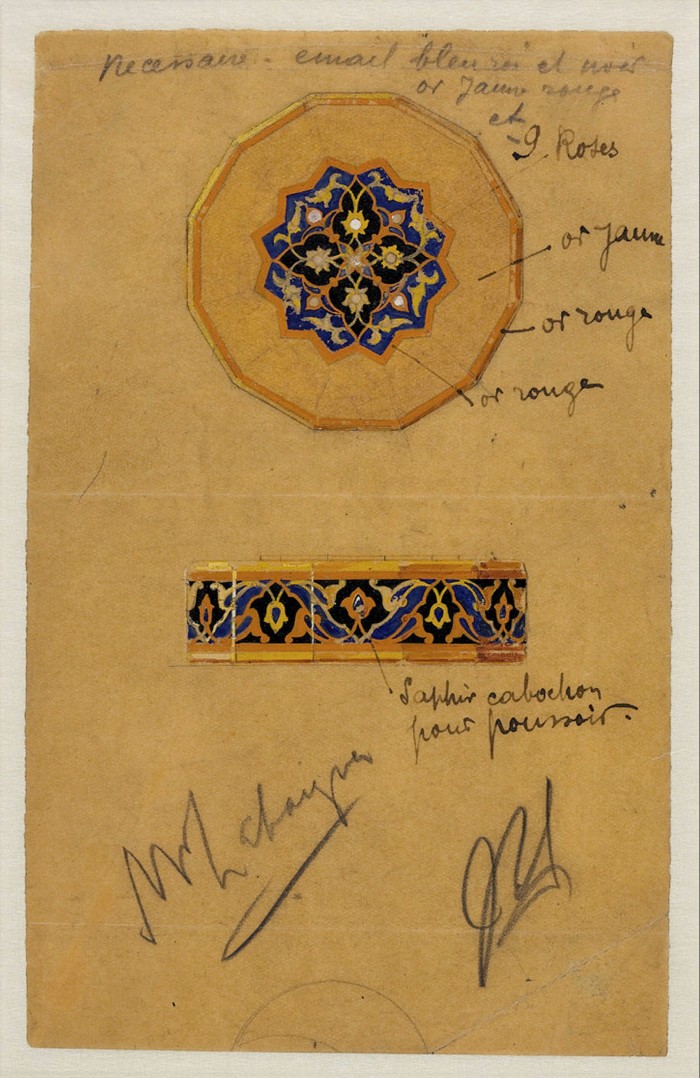

The exhibition displays a selection of the objects and decorated manuscripts Louis would bring to his atelier, inviting his designers to seek inspiration in them.

The arabesque of intertwining vegetable patterns of a cylindric ivory vessel known as pyxis is echoed in a cigarette case in gold, enamel and onyx, while a recurrent Islamic palmettes motif of a 17th-century court belt is rendered in turquoises in a tiara.

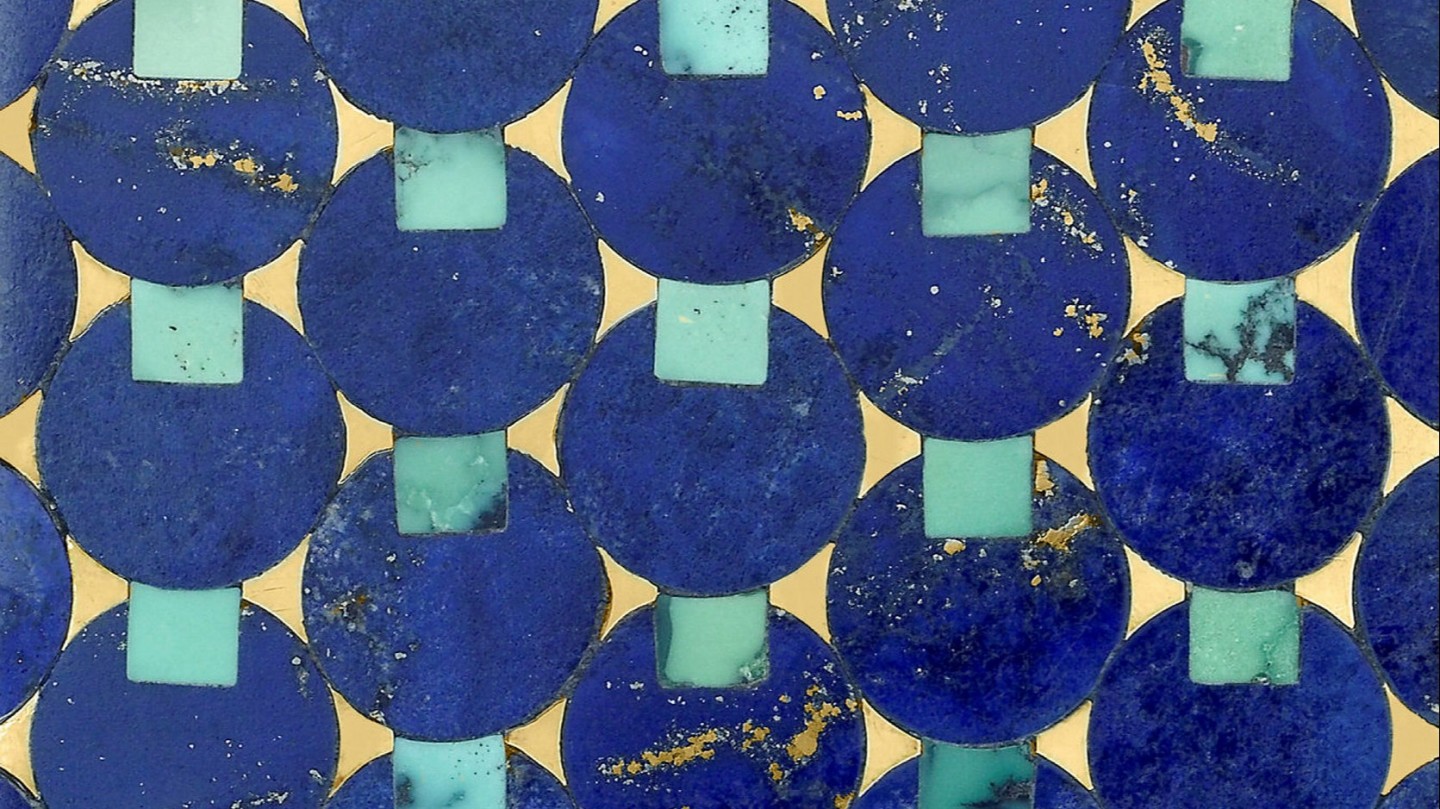

Islamic art also inspired Cartier to combine the green of jade or emerald with the blue of lapis lazuli or sapphire to create his famous peacock pattern.

The same geometrical mandorlas, foliage, plant and floral designs in starkly contrasting colours, that are the vocabulary of Islamic art, permeated the language of Art Deco. A distinct Art Deco feature is the use of apprêt, a genuine artefact of past civilisations inserted in contemporary jewellery.

“Sometimes, original elements of Islamic art have been set in Cartier creations, such as Persian miniatures, carved stones and elements of Mughal jewellery,” says Rainero.

Apprêts transform a piece of jewellery into a unique work of art impossible to reproduce — which inevitably bolsters Art Deco jewellery’s desirability and its price in the vintage market.

“These pieces probably do achieve higher results if compared to a similar jewel from another time,” observes Jessica Wyndham, Sotheby’s head of European jewellery sales — a fact that she attributes to the enduring modernity of the style.

Meanwhile, auction houses have been reporting increased demand for Art Deco jewellery during the pandemic. Alongside the signed Art Deco pieces by Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Boucheron, Chaumet and Mellerio, those by now extinct houses such as Lacloche Frères, Jean Després, and Fouquet have experienced robust demand and commanded high prices.

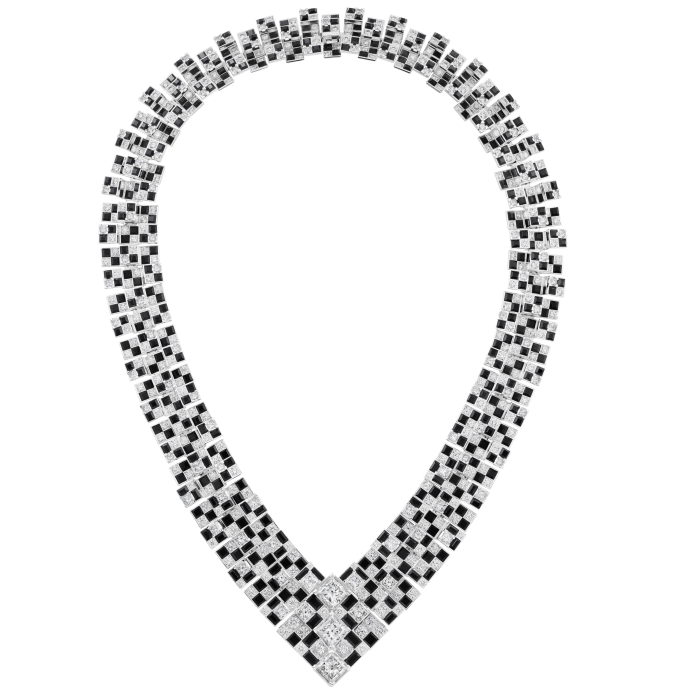

Yet original Art Deco jewellery can appear so modern that it is often difficult to distinguish it from Art Deco-inspired contemporary pieces.

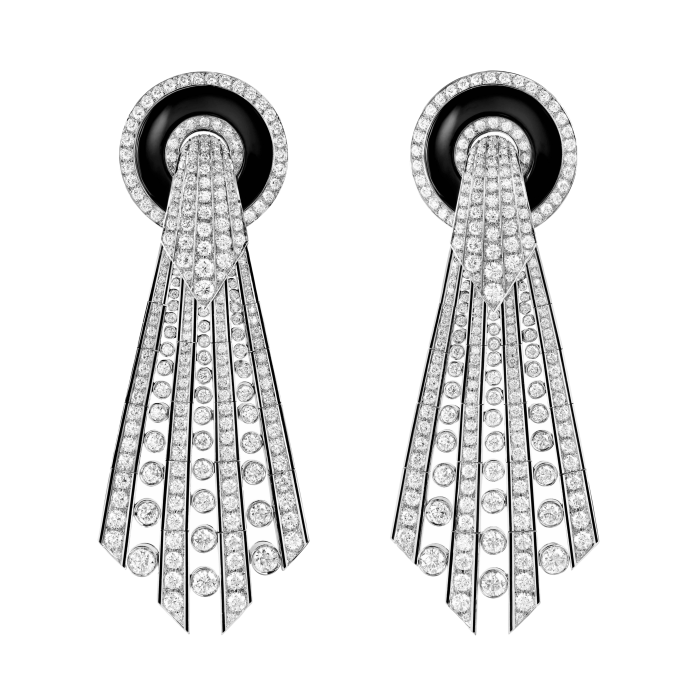

This has emboldened houses to reference the 1920s and 1930s in their collections freely. Cue the black and white chessboard motif of the Cartier Meride necklace rendered in onyx, diamonds and rock crystal; or the jagged fringe of emeralds and sapphires in the Nuée d’émeraudes necklace by Van Cleef & Arpels; or, again, the split oval lines of the Chaumet’s Labyrinthe brooch in white gold and onyx with baguette-cut green and pink indicolite tourmalines and jade.

Boucheron’s January high jewellery collection — titled Histoire de Style, Art Déco — was entirely inspired by the brand’s 1920s and 1930s archives, with modern creations articulating Art Deco’s idiosyncratic contrast between purity of lines and opulence of colours and materials.

“Our clients and collectors have a lot in common and, quite naturally, clients are influenced by this iconic style when buying contemporary jewellery,” says chief executive Hélène Poulit-Duquesne.

“Unquestionably, [Art Deco] is truly a period that is known to the greatest number,” agrees Jean-Marc Mansvelt, chief executive of Chaumet, adding that the brand references the period moderately among its designs.

As one of the most bankable styles, Art Deco has also attracted contemporary designers. In his Athens atelier, Nikos Koulis imbues his jewellery with the geometrical lines of the style and a signature use of black enamel and rock crystal. In a similar nod to Deco principles, London-based jewellery designer Glenn Spiro often uses apprêts such as triangular shaped 3,000-year-old Egyptian ceramic tiles or carnelian sections dating from the first millennium BC.

In addition, the world’s attempts to recover from the coronavirus pandemic have drawn numerous other parallels — in both arts and economics — with the exuberance of the bygone era that emerged after the first world war and the Spanish flu pandemic, and continued into the 1920s and 1930s.

Perhaps, as Sotheby’s Wyndham suggests, the enduring popularity of Art Deco can be traced to a “certain glamour associated with that time” and the desire for experimentations that defines it.

As far as jewellery sales are concerned, comparisons with the buoyancy of the Roaring Twenties bear some scrutiny. Swiss luxury group Richemont posted a 43 per cent increase in sales for its jewellery houses in the first quarter of 2021, while rival LVMH’s watches and jewellery business recorded a growth of 4 per cent in its third quarter of 2021 compared with 2019.

It may not all be attributable to Art Deco-inspired jewellery, but it undoubtedly makes investors’ reports more pleasing to the eye.

‘Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity’ runs until February 20 2022 at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs

Comments