Macho ‘brogrammer’ culture still nudging women out of tech

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Miranda is quitting her competitive software engineering job in London, even though she loves the work. While technology companies including Google and Uber have been plagued by sexual harassment allegations in recent months, female coders like Miranda are leaving their dream careers because of more subtle forms of discrimination pervading the industry.

“It is death by a thousand paper cuts and managers not believing you are bleeding,” says Miranda (not her real name) who, like the other female developers interviewed for this article, requested to remain anonymous. “These things can seem like small problems or nothing at all to someone hearing them for the first time [but] by the time you are telling someone, you have been ground down.”

One of few women in her department at a medium-sized global technology firm, Miranda has worked as a coder for the past eight years. She describes how she is interrupted or ignored in meetings on a daily basis. Male colleagues are given credit when they re-announce ideas that she has already presented.

She is equally repelled by the office culture, which she finds unwelcoming for women — as well as many men — with heavy drinking, colleagues firing large foam darts at her while she is working and trying to one-up each other. In her previous job there was a similar atmosphere, she recalls, with men casually sharing porn around the office. A company party once featured a female stripper covered in whipped cream.

For decades, we have focused on encouraging girls to go into Stem and hiring more women. But we are placing them into environments that aren’t welcoming and they are chased out of the company

Jennifer Berdahl, professor of gender and diversity at the university of British Columbia

“This is tech company office culture,” says Miranda. “A macho ‘brogrammer’ culture that pushes women away,” including many she knows personally.

More women than ever before are taking computer science degrees and entering the technology profession but the culture problem persists, says Jennifer Berdahl, professor of gender and diversity at the University of British Columbia.

“For decades, we have focused on encouraging girls to go into Stem [science, tech, engineering, maths] and hiring more women,” she says. “But we are placing them into environments that aren’t welcoming and they are chased out of the company.”

The consequences of a challenging work atmosphere go far beyond diversity. Prof Berdahl’s research shows that offices with “masculinity contest” cultures tend to have toxic leaders, higher staff turnover, more workers suffering from illness and depression, and higher rates of sexual and racial harassment and bullying.

“It is really tiring, job after job after job, this feeling of having to leave because of someone else,” says Penny (not her real name), who has worked in technology for more than a decade and quit working for a tech consultancy last year, along with two other female colleagues.

Penny has three engineering degrees, including a PhD, but in her last job was tasked with ordering groceries, taking notes during meetings with customers and organising social events. A male colleague without professional coding qualifications, meanwhile, was given the bulk of the technical work. Another male colleague would answer any questions directed at her during meetings, she recalls.

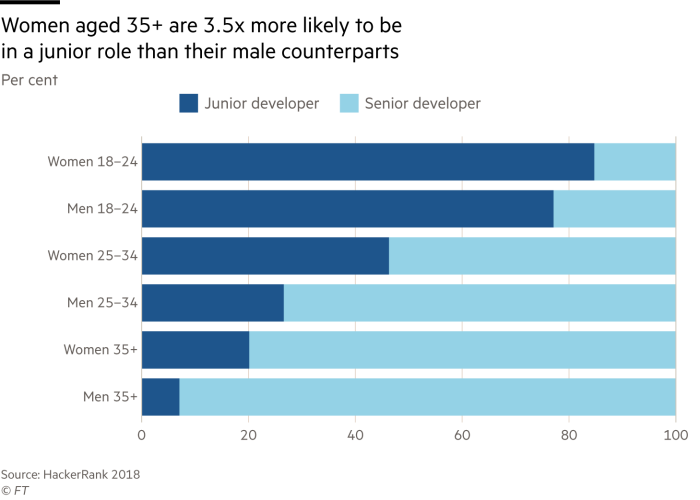

This year, the hiring platform HackerRank surveyed more than 14,000 professional software developers globally, 2,000 of whom were women. It showed that 20 per cent of female developers over the age of 35 were still in junior positions, compared with only 6 per cent of men. Women in that age bracket were about 3.5 times more likely to be in junior positions than male counterparts, the report found.

When Penny challenged her boss, she was told: “Taking notes is a very important part of the meeting and there is nothing wrong with making coffee.”

For a year, she suffered with insomnia and lay awake rehashing the sexist treatment she experienced. She frequently burst into tears when talking to her boss. “It was horrible,” says Penny, who has since moved to a larger tech firm, where she says she is happy. “I felt a huge sense of injustice that consumed me.”

Joanna (not her real name) quit her senior engineering job at IBM a couple of years ago, after being “supremely micromanaged” by a superior who gave her “incredibly low-level” duties. She recalls how on one occasion her manager explained to her how to open a zip file. She has an engineering degree and had worked at the company for more than two decades, but she could not see a future there.

She thinks that the solution is not just about changing companies’ policies. Joanna believes her former employer tried hard to improve diversity, and had good maternity and anti-harassment procedures in place. “They have fixed almost all of the conscious stuff,” she says.

Yet it could still be a difficult place for senior female technical staff, says Joanna, who is now a tech founder and developer.

“As you become more senior it becomes harder to sit in meetings and watch people ignore you and talk over you, so women drift.”

If the entrenched masculine culture across technology is to change, says Prof Berdahl, companies need to begin by better measuring the problem. This should include disclosing how many technical tasks are assigned to men versus women, conducting more annual employee surveys and ensuring that managers challenge even minor examples of discrimination.

As for Miranda, she says she is scarred by her experiences, but remains determined to find a workplace where she is able to do the job that she loves.

“I am now a lot more selective about where I will work,” she says. “None of that [dislike of the macho culture] has got any bearing on my abilities as a programmer.”

Comments