Frieze London: women at work

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

A feminised Frieze art fair this year is welcome, spirited, engaging and in tune with institutional trends.

Half the artists in Frieze Sculpture (on display in Regent’s Park) are women, and major women-only presentations at Frieze London include 2017 Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid, 2018 Turner nominee Charlotte Prodger and Cathy Wilkes, who will represent Britain at 2019’s Venice Biennale — all feminist conceptualists. But does Frieze 2018 fully reveal the complexities of women’s participation in today’s art world?

Edgy juxtapositions are what make Frieze popular. At Deutsche Bank’s Wealth Management lounge Tracey Emin celebrates “female political empowerment” by curating an all-women show, including significant political artists such as Marlene Dumas and Kara Walker. There is a spin-off sale of postcard-sized works by the artists, to benefit domestic abuse charities.

Complementing the wave of senior women solo shows sweeping London’s commercial galleries this week — Yayoi Kusama opens at Victoria Miro, Doris Salcedo at White Cube, Kiki Smith at Timothy Taylor — Frieze’s own contribution is “Social Work”, a historic gathering, centred on the 1980s, of women artists who “challenged the status quo and explored the possibilities of political activism”. This invited section curated by various galleries, with selectors including Whitechapel Gallery director Iwona Blazwick, follows last year’s special display “Sex Work”, but it is broader, more serious, less exclusive of men and, crucially, only half the artists are white. (“Sex Work” featured solely white artists.)

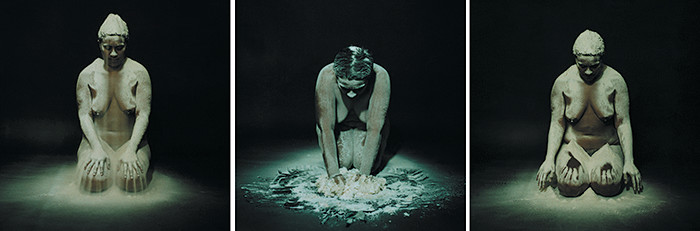

The oldest artist in “Social Work” is 89-year-old Harlem-born Faith Ringgold, celebrated for her storytelling quilts and paintings about race relations and black American experience. The youngest is Berni Searle, 54, who paints her own body — the “Colour Me” series — to question post-apartheid narratives in her native South Africa. Least known is probably Turkish Ipek Duben; on show is her 1981 “Sherife” series of paintings of Anatolian migrant women, and nudes transformed as patterns in Islamic miniature tradition.

Particularly gratifying is the presence in Frieze’s commercial heartland of artists who made careers outside the gallery system, such as multimedia forerunner Tina Keane. For me, photographs of her 1977 performance applying lipstick while holding a mirror engraved “SHE” and “MALE ORDER CATALOGUE” viscerally evoke angry/earnest/idealistic discussions among young women at that time, while her video “Faded Wallpaper” (1988) is a metaphor for women’s invisibility and inexpressiveness and, as the patterning of the decoration slowly merges with the protagonist, fears of self-disintegration.

Although arranged as monographic displays, thematic and formal links — for example in uses of text — are pronounced. Keane connects with the language-based practice of Americans Nancy Spero and Mary Kelly (“Corpus”, 1984-85, juxtaposes notes from women’s everyday conversations with neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot’s classifications of hysteria).

Such associations are absorbing and more: they feed scholarship as 20th-century art is reassessed to acknowledge myriad individual achievements, outside the (male-led) mainstream, which nevertheless echo with each other and, we see now, form a history.

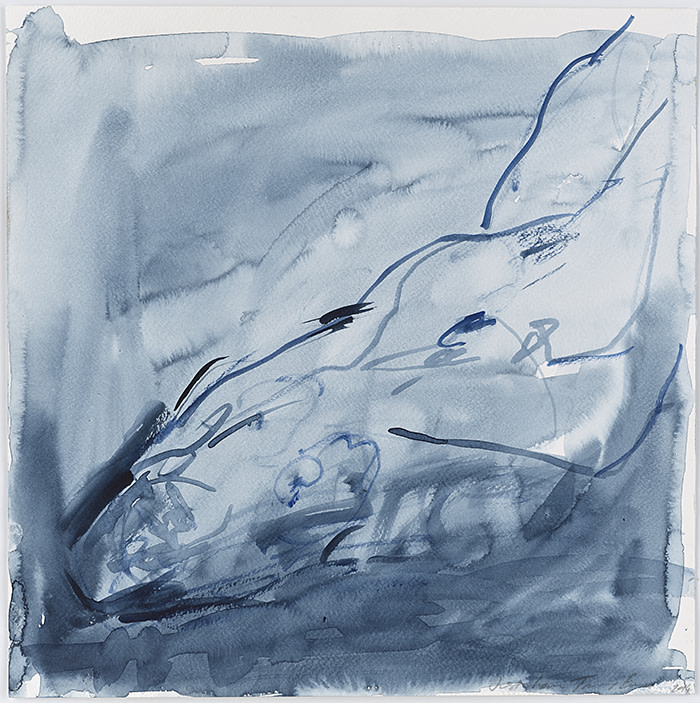

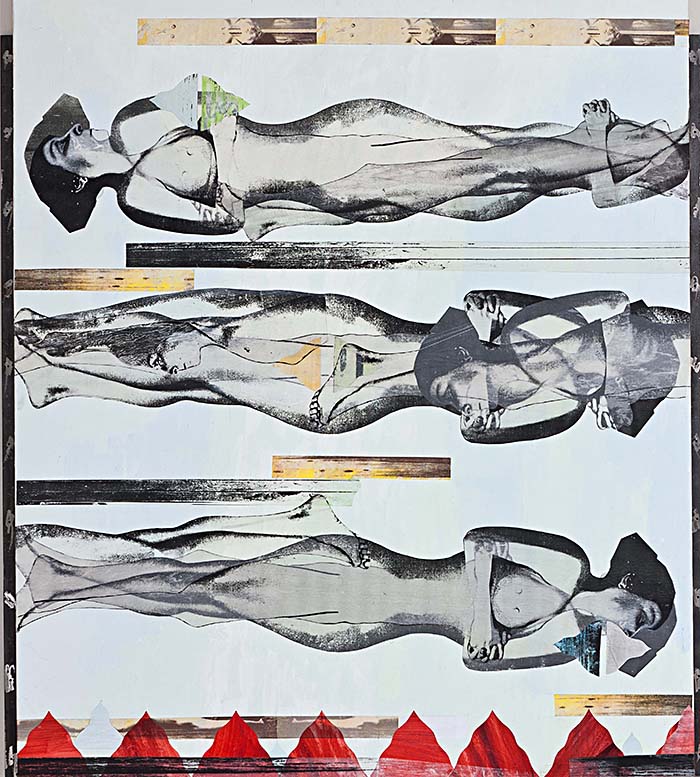

Sonia Boyce, the black British artist exhibiting “Auditions”, a performance/photographic piece of people donning Afro wigs, exploring identity’s collective construction, says she is excited to show alongside Helen Chadwick, who was “so important for all of us”. Chadwick is seminal to feminist art history — in “Domestic Sanitation” (1976) latex-clad women act out absurd beauty rituals — but still more resonant beyond it, in her tableaux questioning relationships between pleasure and revulsion: here the silk, meat and lightbulb tabletop photographs “Meat Abstracts” (1989) and the golden locks entwined with pig intestine “Loop My Loop” (1991).

How does “Social Work” relate to women artists today? Two things struck me. First, what a long wait. Chadwick died in 1996, Spero in 2009, and all but two of the remaining artists are over 70. Older women artists have been intensely fashionable since Tate Modern’s inauguration with the spider “Maman” by Louise Bourgeois, then 88. Bourgeois, obscure for most of her career, became a 21st-century celebrity; versions of this trajectory followed globally — Carmen Herrera, born 1915, Cuba; Maria Lassnig, 1919, Austria; Kusama, 1929, Japan.

Is it possible that women artists become beloved in old age not only because their work, often offbeat, makes better sense when seen as a coherent decades-long oeuvre, but also because, as women in society, they are no longer sexually powerful and therefore less of a threat? “You are supported until your mid-thirties, then you become less of a girl, more of a threat — at that point women get overlooked,” says distinguished painter Celia Paul, 59. She has never had a UK public gallery solo show; nor have other exceptionally gifted, thoughtful British non-conceptualists aged between 60 and 70: painter Lucy Jones, and sculptor Emily Young. I don’t think this is the case for male artists of equivalent quality.

So, second, a reservation: while “Social Work” and a feminised Frieze are engrossing prospects, as long as the market and museums continue to excavate women’s achievement almost entirely within the context of gender politics, other voices, as important and original, remain too little heard. The story isn’t over yet.

October 4-7, frieze.com; deutschewealth.com

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Letter in response to this article:

Not ‘women artists’— simply ‘artists’ / From Rea Stavropoulos, London, UK

Comments