Troy Carter — from managing Lady Gaga to collecting blue-chip art

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I didn’t even know I was a collector until somebody wrote an article calling me one!” says Troy Carter. But he certainly knows now: last year he was in the Artnews Top 200 collectors list; he is a trustee of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and sits on the board of the California Institute of the Arts. He also works closely with artist Mark Bradford on his youth outreach programme Art + Practice, as well as other schemes for underprivileged children.

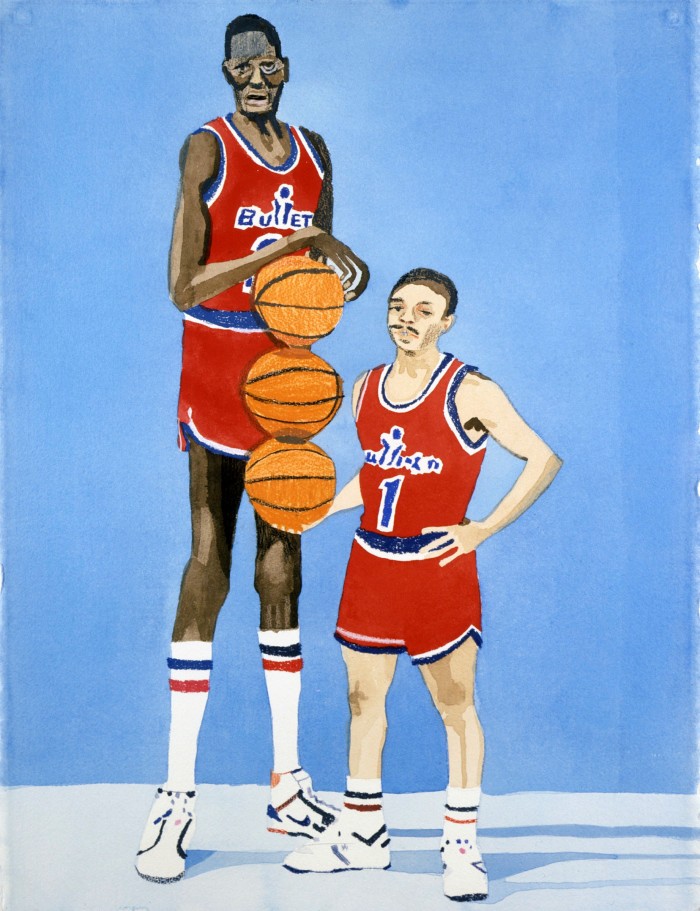

Carter, 48, is well placed to understand them: his own path has not always been easy. He was born in the suburbs of West Philadelphia where his parents’ means were far from those of many people he now knows. “The walls of black people’s homes like mine were decorated with velvet glow-in-the-dark pieces; almost all had portraits of Jesus Christ, Martin Luther King and John F Kennedy,” he says, speaking over Zoom from his home in Martha’s Vineyard, wearing a simple striped T-shirt. (He also has a house in Los Angeles and “a few others”.) He is thoughtful and approachable, coming across calm and confident.

Carter is part of a new generation of black collectors, focusing on supporting black artists, collecting their work and making black culture better known to the general public, alongside people such as Suzanne McFayden, Pamela Joyner or former basketball star Elliot Perry.

In the music business since he was a teenager, Carter was Lady Gaga’s manager for the first six years of her career; head of creator services at Spotify, where he managed artist relations; and is now co-founder and chief executive of Q&A, a music distribution and management platform. He is also entertainment adviser to the estate of Prince, who died in 2016, responsible for sorting out its business affairs. I say that his five children must think he’s the coolest dad around; he laughs: “No! Dad is never cool for them. Their friends think I’m cool, but not my kids.”

Carter has been a collector for about 10 years now — “originally it was really about buying pieces to put on the walls” — but the art world took notice in 2018 when he paid $730,000 for a Rashid Johnson, “Untitled Escape Collage” (2018), at a charity auction. Other African-American artists in his collection are Bradford, Theaster Gates and Lauren Halsey (all friends), as well as Glenn Ligon and Lorna Simpson, and he has pieces by Robert Rauschenberg and Damien Hirst too.

The Covid lockdown did not dent Carter’s collecting; in fact, he says his collection has grown by a quarter over the past year to “a few hundred works”. “I have started putting some of them into an ‘open storage’ facility [where art is viewable and visitable] and am certainly thinking about displaying the whole collection in some sort of a public-access art space in the future,” he says. But owning and managing a collection has been a learning curve. “When I started out, I didn’t understand you lent things out or gifted pieces to museums — these were all completely new concepts for me.”

The move into the art world has had an electrifying effect. “I am absolutely astonished and fascinated by it! It’s such an interesting space, and very close to the music world.”

It’s my turn to be surprised — I had always imagined the two worlds as very different. “They are both very closed ecosystems,” he says. “From the outside the music world looks very big, just as the art world does, but when you lift the hood, everyone knows each other.

“Then there are similarities in the creative project. There is a discipline to becoming a great music producer, just like an artist: you need to get into that studio every single day. You are working as an orchestrator of the idea. It’s the same for artists — they have the vision, but other people help with the execution.”

But he does find a difference in what he calls the imbalance of power. “In the music industry, artists have a really big seat at the table, and I would like to see that happening in the art world as well. I think there should be much more transparency. I think it’s so unfair that an artist may have no idea who has bought their work. And the fact that they don’t profit from an insane increase in price seems deeply unfair.” He mentions the Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo, whose prices went from around $45,000 on the primary market to a stunning $880,000 at auction in a single year. “I don’t quite know what the solution is, but perhaps if something is resold within five years there could be some sort of participation for the artist,” he suggests.

While he considers the high prices now commanded by the likes of Amy Sherald, Bradford or Kerry James Marshall (whose work “Past Times” sold in 2018 for $21m) to be totally in line with their quality, he is more concerned “further down the chain” by the mismatch between quality and price and by high entry-level prices, which shut out early collectors. “I would love to see not just wealthy African Americans collecting this art,” he says. “If you are, say, an African-American schoolteacher, you should be able to afford art by some of the up-and-coming names. At $3,000 or $4,000 that might be possible, perhaps with a payment plan, but certainly not if the artist’s work is starting at $25,000.”

His mother earned less than $40,000 a year, he says, but collecting is about more than money. “We didn’t have financial means growing up but did have a rich inheritance of close supportive family, and part of that support was confidence. A lot of people in the art world have been friends and mentors . . . As a result I didn’t feel the insecurity of not being a person who grew up with million-dollar pictures on the walls.”

Comments