‘No going back’ to oil and gas despite new UK exploration licences

Simply sign up to the Oil & Gas industry myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In recent months, Just Stop Oil protesters have glued themselves to central London roads, blockaded entrances to petrol stations, stopped traffic on a key bridge in the UK capital, attempted to disrupt the British Grand Prix motor race, and thrown a tin of tomato soup over Vincent van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” at the National Gallery.

Since being formed in April this year, the campaign against the use of fossil fuels in Britain has seen hundreds of its supporters arrested. But, far from deterring protests, the cause has been given added impetus by a UK government decision to grant a new wave of oil and gas exploration licences.

Under this programme, the North Sea Transition Authority is expected to award more than 100 permits to companies to explore for oil and gas on the Continental Shelf by the end of June. It will prioritise four areas in the southern part of the North Sea, where gas has already been discovered.

Protesters have signalled that they will mount a legal challenge. Environmental group Greenpeace claimed the new licensing round was potentially “unlawful” and indicated it would aim to block it in the courts. Climate campaigners have stressed that the UK government’s attempts to secure more oil and gas from the North Sea conflicts with its commitment for the UK to have net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

The British government claims maintaining North Sea oil and gas production is justified by Russia’s attack on Ukraine and denial of gas supplies to Europe, which it says underscores the need for energy independence.

But experts say it remains unlikely that any increase in oil and gas production in the North Sea would lower prices in the UK, as they are set by international markets.

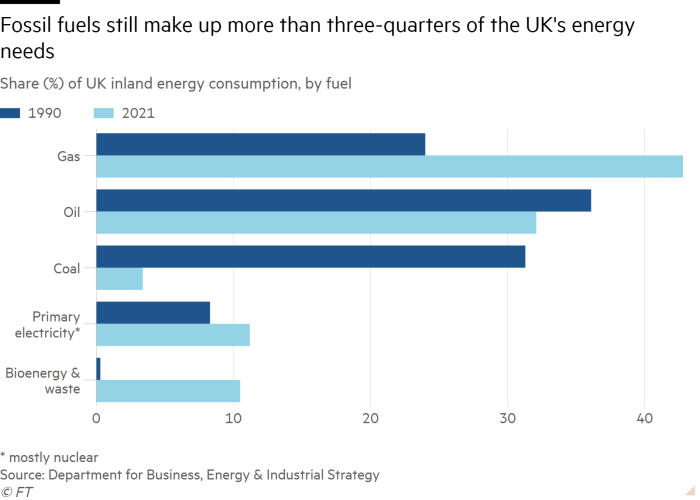

Despite this, Offshore Energies UK, the industry trade body, argues that oil, gas and electricity still provide almost three-quarters of the UK’s energy needs, so it is necessary to maintain domestic production to reduce reliance on imports. Last year, Britain imported 62 per cent of its gas needs and 18 per cent of its oil, according to an Offshore Energies report.

“Recent exploration activity levels in the UK Continental Shelf are lower than necessary to sustain reserves and meet UK demand,” says Mark Wilson, operations director at Offshore Energies UK.

The UK still has oil and gas reserves equivalent to 15bn barrels of oil that could be exploited, the organisation says. If investment of £26bn could be secured this decade, Britain could still meet half its oil and gas demand domestically by 2030.

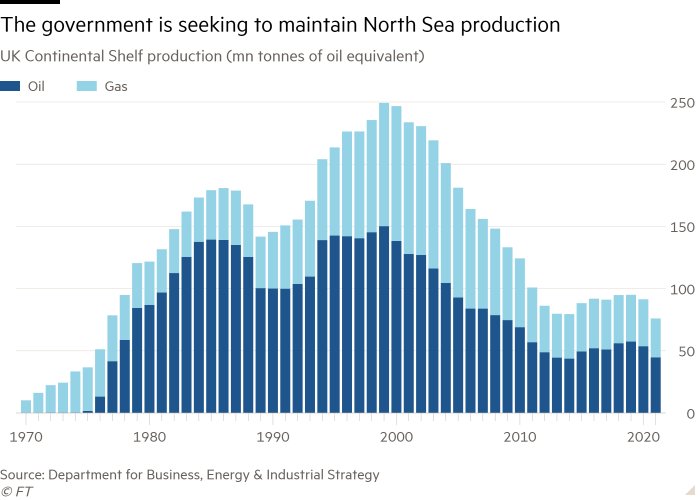

However, while Offshore Energies says production can be increased, even it acknowledges that, after 50 years of exploration, the North Sea is a declining field. Output has been falling by about 5 per cent a year and the deposits that are left are generally harder to extract.

Even if fields adjoining existing sites can be harnessed for production within months, new developments can take years to come on stream, so the new licensing rounds are unlikely to reverse the long-term decline.

This has made the region less appealing to the big industry players, such as BP and Shell, which have chosen to divest themselves of North Sea assets in recent years — leaving smaller players, such as Aim-listed IOG and Neptune Energy, with the biggest appetite to increase production.

Andrew Latham, an analyst at Wood Mackenzie, says there are only “modest” opportunities in the North Sea and he doesn’t see much scope for that to change. “There are occasions where there is a surprise find, but it’s unlikely,” he notes.

Global upstream oil and gas investment has fallen from $700bn since 2014 to $400bn a year and there is “no going back”, Latham says.

A UK windfall tax on oil and gas explorers could also deter UK investment, he says, although it has largely been offset by a generous investment tax relief, which rewards companies with an overall 91p saving for every £1 they commit.

The shift to renewables means there is less certainty about the duration of demand — and that affects the appetite from the larger oil and gas developers to pump resources into the Continental Shelf. “If you’re not sure how much oil and gas is going to be needed, you don’t want to invest,” Latham explains. “A lot of the message is that fossil fuels aren’t wanted.”

Ultimately, they are counterproductive, says Simon Retallack, director of the Carbon Trust’s Net Zero Intelligence Unit. He points out that even the International Energy Agency has warned that expanding oil and gas exploration could significantly set back the transition to renewable energies, threatening the UK government’s net zero targets. “Prioritising renewables would deliver a cleaner, greener energy system, make the UK more resilient to global shocks in the price of oil and gas, and deliver more jobs to support UK growth,” says Retallack.

But, until the UK can develop significant storage that can deal with the intermittency of wind and solar power, there will still be demand for gas and oil.

The best solution, suggests Latham, may be to cut back on the need for more fossil fuels by better insulating homes, for example, rather than targeting the supplier companies. “If you’re really going to focus on reducing emissions, you need to focus on demand — so the activists’ decision to protest at petrol stations and roads is interesting, as it puts pressure on everyone,” he says.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments